The book of Revelation is full of horrifying imagery. In the culminating book of the whole biblical story, John of Patmos narrates an end-times battle royale of monstrous armies and a harvest of human grapes that leads to blood flowing from a winepress. It ends with the sinners being thrown into a lake of fire. This should give any Christian pause before claiming that the New Testament is a book of peace.

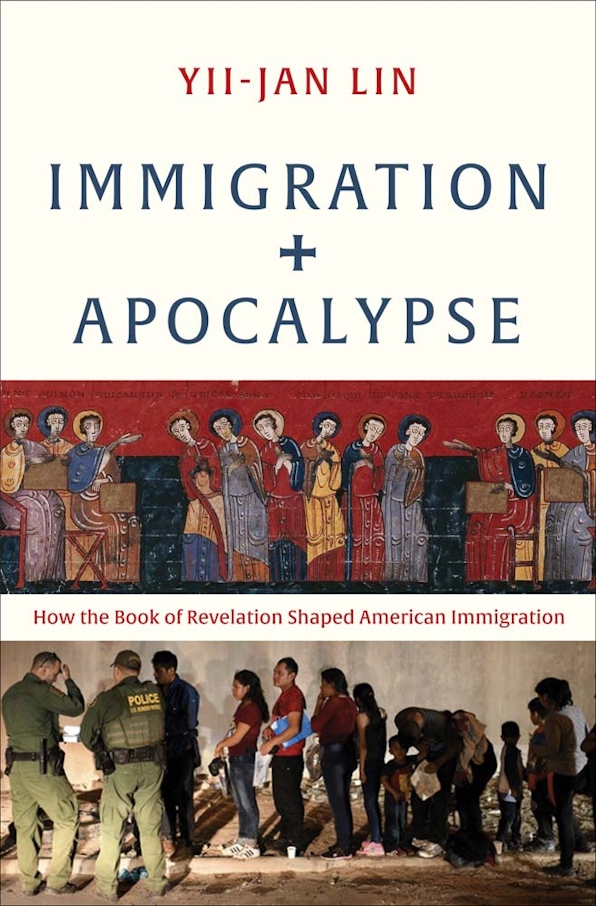

But for Yii-Jan Lin, associate professor of New Testament at Yale Divinity and author of Immigration and Apocalypse: How the Book of Revelation Shaped American Immigration, the explicit violence is only part of the problem of Revelation. Even more troubling is the vision of the “New Jerusalem” that will arise: a city for God’s chosen, with the undesirables left outside the gates. It’s this vision of exclusion, Lin argues, that has been the central religious authorization for the United States’ immigration policies.

The U.S. has always considered itself as this New Jerusalem — a land specially blessed by God — but also one that is only available to those specially chosen. And from the establishment of the United States as a nation, as Lin discusses, this drive to only welcome certain individuals has been heavily focused on questions of race and national origin. The notion that the U.S. is a nation that welcomes immigrants is a myth that contradicts historical record. Instead, our “[i]mmigration and naturalization laws serve ultimately to create the ideal population as conceived by those who set policy and legislate,” Lin writes.

Lin acknowledges the U.S.’s vile treatment of Indigenous populations and enslaved people, and reads these stories alongside the “apocalyptic exclusion of Chinese immigrants.” These immigrants were welcomed in the early 1800s as necessary labor for the completion of the transcontinental railroad. When all the tracks were set, however, they became the object of racist vitriol, including the Naturalization Act of 1870, which did not allow for a process of citizenship for people of Chinese descent. In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act officially banned Chinese immigrants, with exceptions for certain categories.

As Lin carefully argues, so much of the rhetoric surrounding immigration debates is steeped in the language of Revelation. As a painful example, Lin shares an editorial cartoon published in Harper’s Weekly in 1898, in which a band of sword-wielding angels look in horror at a “colossal flaming Buddha,” who rides on a dragon of storm clouds. The cartoon was entitled “Yellow Peril.”