As cities across the country and around the world struggle to cope with the ongoing pandemic, it is an opportune time to read Saving America’s Cities, Lizabeth Cohen’s excellent study of postwar urban planning. The period she chronicles is at once near and far from our own. Over the years that followed World War II, the federal government sought to address the problems of urban poverty and deindustrialization through a series of attempts at urban renewal. Much of the historical literature on these programs has focused on their failings—especially and most damningly with regard to public housing, which created what scholar Arnold Hirsch, writing about Chicago, called a “second ghetto.” Cohen, by contrast, views the contradictory legacy and aspirations of postwar urban liberalism as having much within them to admire, a case she makes by taking up the life of urban planner Ed Logue.

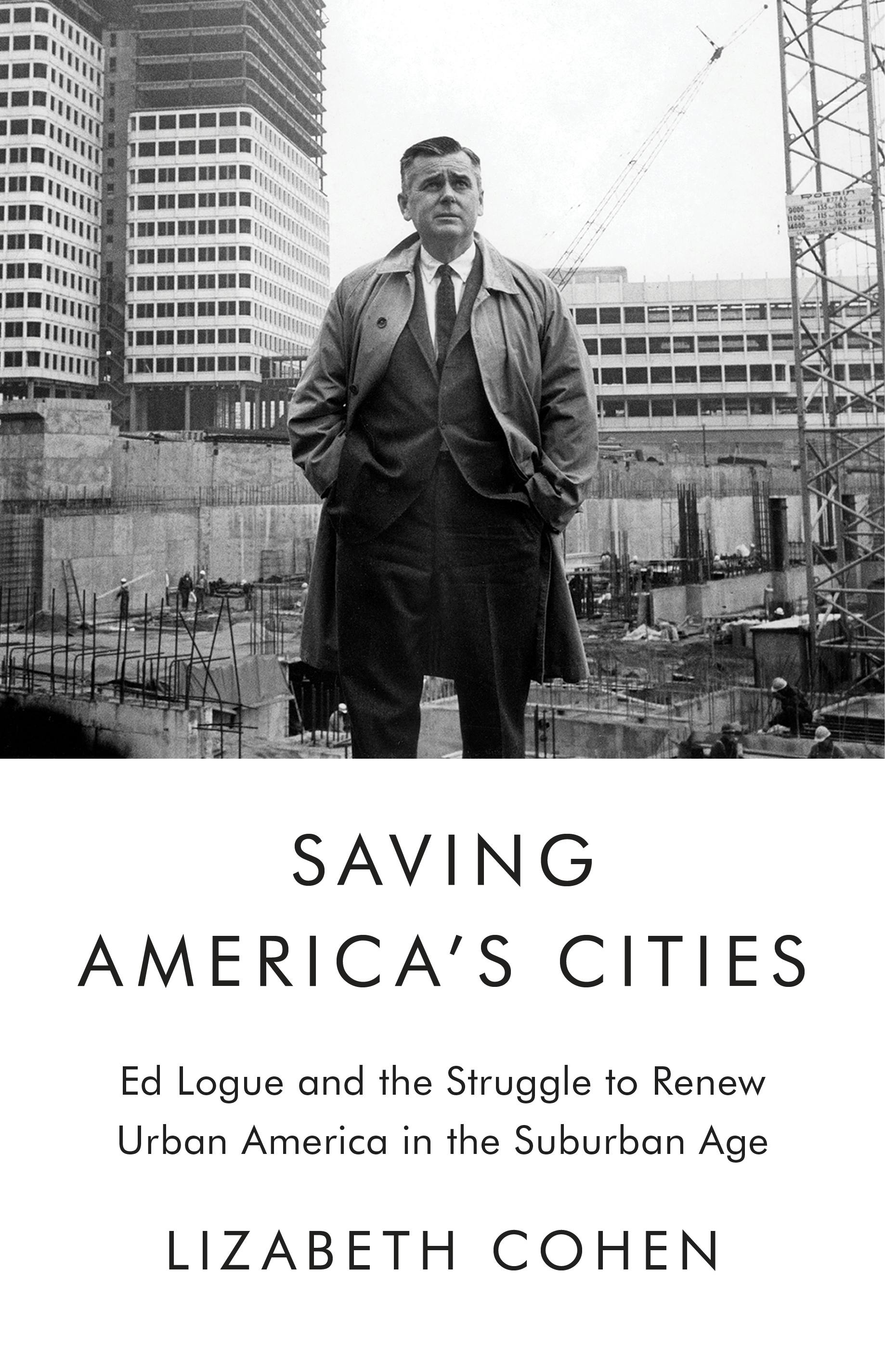

Logue’s name is little known today, but he was a renowned figure in the mid-20th century, dubbed “Mr. Urban Renewal” by The New York Times and the “Master Rebuilder” by The Washington Post. He brought federal redevelopment money to New Haven. He used public money to rebuild downtown Boston. He built the apartment towers on Roosevelt Island for New York City as well as affordable housing elsewhere throughout the state. For Cohen, his career was representative of a certain liberal hope: that professional expertise and federal funds could reverse the racial inequalities, suburban flight, unemployment, and disinvestment that plagued American cities in the second half of the 20th century.

Cohen makes a compelling case that a renewed faith in the public sector and the active participation of the federal government in rebuilding urban infrastructure and public housing are essential for any progress today, and she argues that Logue’s work demonstrates the potential of this approach as well as some of its successes, however partial. Yet at the same time, Saving America’s Cities is, purposefully or not, a study in urban liberalism’s failings and of the profound pressures that always constrained and shaped its aspirations and accomplishments. In the end, Logue’s career—which began with his trademark sunny confidence and brash appeal but ended with his back against the wall of declining federal money and slipping public support—cannot help but suggest the limits of postwar urban renewal as much as its possibilities.