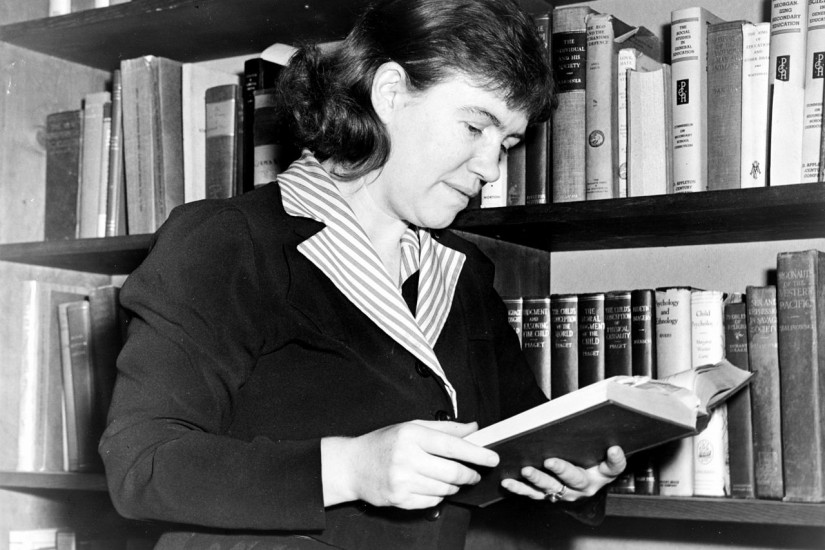

Not that long ago, Margaret Mead was one of the most widely known intellectuals in America. Her first book, “Coming of Age in Samoa,” published in 1928, when she was twenty-six, was a best-seller, and for the next fifty years she was a progressive voice in national debates about everything from sex and gender to nuclear policy, the environment, and the legalization of marijuana. (She was in favor—and this was in 1969.) She had a monthly column in Redbook that ran for sixteen years and was read by millions. She advised government agencies, testified before Congress, and lectured on all kinds of subjects to all kinds of audiences. She was Johnny Carson’s guest on the “Tonight Show.” Time called her “Mother to the World.” In 1979, the year after she died, President Jimmy Carter awarded her the Medal of Freedom.

Today, Margaret Mead lives on as an “icon”—meaning that people might recognize the name, and are not surprised to see her face on a postage stamp (as it once was), but they couldn’t tell you what she wrote or said. If pressed, they would probably guess that Mead was an important figure for the women’s movement. They would be confusing Mead’s significance as a role model (huge as that undoubtedly was) with Mead’s views. Mead was not a modern feminist, and Betty Friedan devoted a full chapter of “The Feminine Mystique” to an attack on her work. Mead mattered for other reasons. One of the aims of Charles King’s “Gods of the Upper Air” (Doubleday) is to remind us what those were.

Mead was a cultural anthropologist, and the rise of cultural anthropology is the subject of King’s book. It’s a group biography of Franz Boas, who established cultural anthropology as an academic discipline in the United States, and four of Boas’s many protégés: Ruth Benedict, Zora Neale Hurston, Ella Cara Deloria, and Mead. King argues that these people were “on the front lines of the greatest moral battle of our time: the struggle to prove that—despite differences of skin color, gender, ability, or custom—humanity is one undivided thing.”

Cultural anthropologists changed people’s attitudes, King believes, and they changed people’s behavior. “If it is now unremarkable for a gay couple to kiss goodbye on a train platform,” he writes, “for a college student to read the Bhagavad Gita in a Great Books class, for racism to be rejected as both morally bankrupt and self-evidently stupid, and for anyone, regardless of their gender expression, to claim workplaces and boardrooms as fully theirs—if all of these things are not innovations or aspirations but the regular, taken-for-granted way of organizing society, then we have the ideas championed by the Boas circle to thank for it.” They moved the explanation for human differences from biology to culture, from nature to nurture.