Having split from co-denominations in the North over the theological justification of slavery in the 1840s, southern Baptist, Methodist, and Presbyterian churches refused to reconcile themselves to a new reality in the 1860s and 1870s. In 1874, for instance, the Southern Methodists’ General Convention reaffirmed their “attitudes and actions in the antebellum period,” historian Elizabeth L. Jemison writes in her exploration of proslavery Christianity after Emancipation.

Baptist and Methodist churches had opposed slaveholding members in the early years of the Republic. These denominations’ rapid expansion in the South, however, meant abandoning this position “in recognition that upwardly mobile members increasingly included slaveholders.” Justification for slavery came with this growth and found its parallels in the biblical subordination of women.

“Southern ministers had written the majority of all published defenses of slavery.” For these ministers, slavery not only had divine sanction, it was a necessary part of Christianity. This was because slavery was defined as akin to a marriage: the “power of slave owners over slaves paralleled the power of husbands over wives and of parents over children.”

The father/master was supposed to be a benevolent and paternalistic overseer of all family members. After all, the New Testament’s “injunctions for slaves to obey their masters appeared alongside instructions for wives to obey their husbands.”

This hierarchy placed white men at the top, because slaves were incapable of ordering themselves. Even northern theologians agreed on the necessary subordination of women: Charles Hodge, who held an influential position at Princeton Theological Seminary, wrote “We believe that the general good requires us to deprive the whole female sex of the right of self-government.”

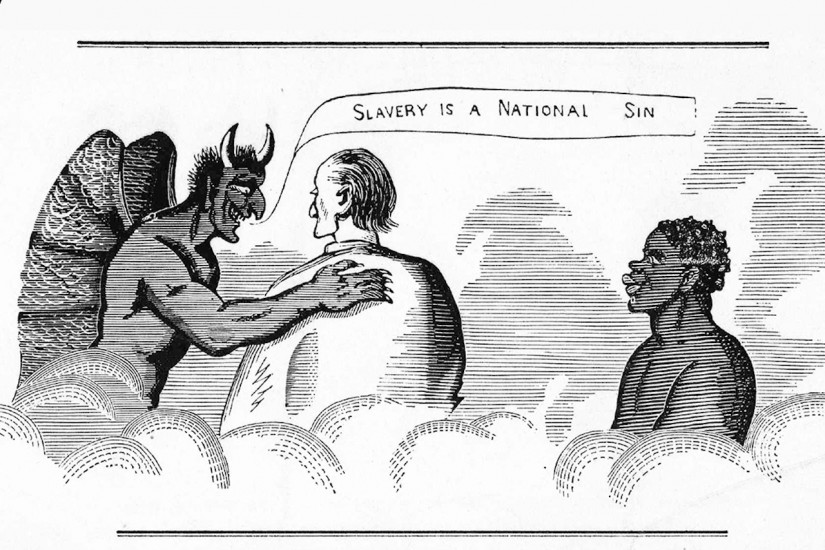

As abolitionism gathered strength, white Southerners repositioned themselves from an acceptance of slavery as a necessary evil to defending it as a positive good. Theological justification from their ministers allowed them to believe that “not only did God sanction slavery, but slavery’s supporters were better Christians and more faithful interpreters of Biblical text than were their opponents.” The slave-owning class was small, but it was supported by “the overwhelming majority of churches and ministers.”