By the mid-1970s, advances in medical technology, particularly ultrasound, had given Nathanson a new perspective on fetal life. After the Second World War, scientists had begun turning sonar technology away from submarine warfare and toward women’s bodies. The fetus had gone public.

Before ultrasound, Nathanson viewed abortion as “bloodless, utilitarian problem solving,” he said in an interview with the Los Angeles Times, adding that, with abortion, “a woman had an unplanned pregnancy; all you did was wipe the fetus out.”

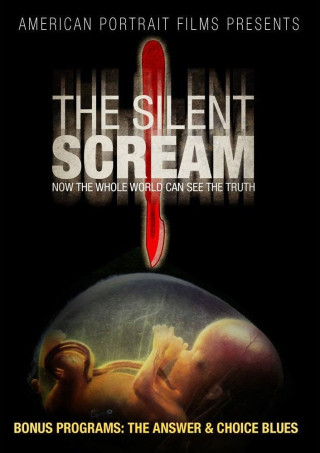

When the pelvic ultrasound gave him a window into the womb, Nathanson began to see the fetus not as an invisible clump of cells, but as something that looked human, with legs and arms, a head, fingers. Something he began to think of as an “unborn child.”

“For the first time,” he wrote in 1974, using humanizing language, “we could really see the unborn child, measure it, observe it, watch it, and indeed bond with it and love it.”

And if a fetus looks like us, Nathanson began to wonder, does it also feel pain like us?

Reagan certainly thought so. Ten years after Nathanson’s change of heart, the Republican president was quoted saying a fetus “often feels pain” during an abortion — “pain that is long and agonizing.” In his memoir, “The Hand of God: A Journey from Death to Life by the Abortion Doctor Who Changed His Mind,” Nathanson credited Reagan with first broaching the topic of fetal pain. “I mulled it over,” Nathanson wrote, “and I thought there’s only one way we can resolve this issue, and that’s by photographing an abortion, beginning to end.”