The right to seek asylum has long been enshrined in domestic and international law. And yet a new rule proposed by the Trump administration would make it all but impossible for most people to apply for asylum at the southern border. The administration’s policies of separating families and indefinitely detaining asylum seekers, as well as its draconian decision to send asylum seekers to Mexico to await their hearings, are the latest chapters in the administration’s attempt to rewrite the nation’s immigration history and dismantle its asylum laws.

But there is hope for immigrant rights advocates. These critical human rights protections exist because people fought for them — and that is the only way they will be reinstated. The refugee rights movement of the 1980s persisted even in the face of powerful nativist forces. By recognizing the ways people succeeded in ensuring rights protections in the past, we can draw inspiration for the critical battles for immigrant rights ahead.

Since World War II, the principle of refugee protection has been a staple of international politics. When Congress passed the Refugee Act of 1980, it brought the United States in line with its international obligations, creating a permanent system for refugee admissions. Under the act, asylum seekers’ claims were supposed to be considered individually and irrespective of country of origin or mode of entry. A person who flees their home country because of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group or political opinion may seek asylum if they are on U.S. soil or at a port.

But when thousands of people fled right-wing regimes and civil unrest in El Salvador and Guatemala in the early 1980s and tried to make asylum claims in the United States, they were denied by Reagan administration officials. One reason was that these countries’ governments were closely allied with the United States during the Cold War. Another was that people from Central America weren’t white.

And so, the administration tried to classify people from these countries as “economic migrants” —— who didn’t qualify for asylum. The distinction between economic migrants and asylum seekers was formalized in the late 1970s through a special program that rejected Haitian asylum seekers as economic migrants unworthy of protection. Eventually the Reagan administration adopted a “uniform” policy of detaining not only Haitian asylum seekers but also Salvadorans. Many nonwhite migrants from different parts of the world were funneled into detention and denied meaningful access to asylum.

Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) Commissioner Alan Nelson —— who would later work with the far-right Federation for American Immigration Reform to craft the harsh anti-immigrant Proposition 187 in California in the 1990s — dismissed Central Americans’ claims as “frivolous.” The agency detained them under harsh conditions and coerced many to sign “voluntary departure” agreements, thereby denying their right to apply for asylum.

As the INS and Reagan administration curtailed the rights of asylum seekers, activists, legal advocates and migrants worked to defend and expand them. In these efforts, they were motivated by their belief that the United States faced a “moral dilemma,” as historian María Cristina García has shown. Because U.S. foreign policy and interventions in Central America had created the humanitarian crises pushing asylum seekers to depart, the nation “had a responsibility to assist” them.

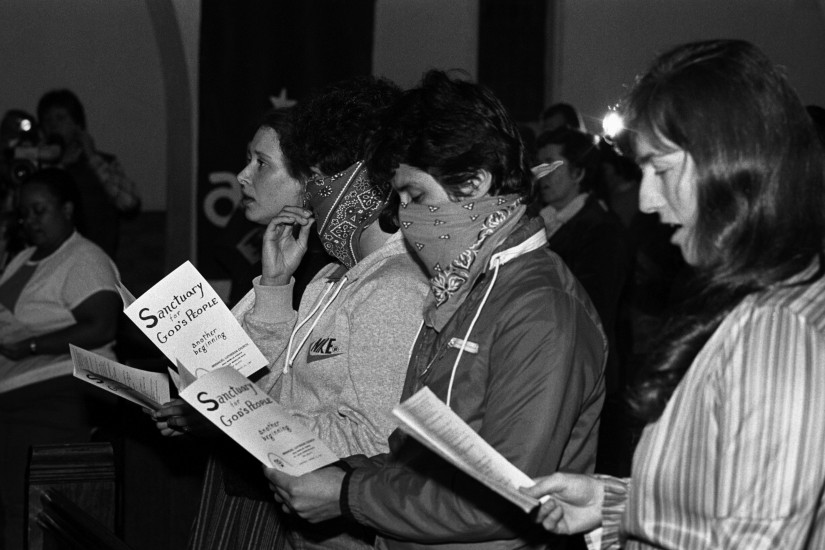

The scope and scale of their advocacy for immigrant rights was unprecedented. Humanitarian organizations educated the American public about how U.S. foreign policy in Central America led to the displacement of millions. They also played a watchdog role by regularly publicizing the abuses suffered by asylum seekers at the hands of the INS. In one of the largest grass-roots movements in American history, the sanctuary movement sheltered and transported Central American asylum seekers. Even when the Reagan administration prosecuted activists for their acts of civil disobedience, the movement continued to grow.

Meanwhile, immigration attorneys filed numerous lawsuits preventing the deportation of Salvadorans and Guatemalans and defending their civil rights. One such case lasted an entire decade, and its outcome still protects Salvadoran asylum seekers. In the Orantes-Hernandez lawsuit that began in 1981, advocates successfully pushed back against coercive tactics that authorities used to force Central Americans to give up their claims. These included threats of solitary confinement and separation of children from their parents.

In a decisive 1988 ruling, the judge required that the INS provide Salvadorans notice of their right to apply for asylum and access to counsel, and mandated certain conditions of detention. As the judge asked during the trial, “when we [the U.S.] have participated and let these things go on [in El Salvador], do we have some kind of responsibility to treat these people a little differently? Isn’t the practice of treating asylum seekers the way we are really contributing to their problem?”

As the Orantes case was being litigated, sanctuary activists, human rights lawyers and immigrant organizations sued the attorney general, charging that the administration had discriminated against asylum seekers from El Salvador and Guatemala. In 1990, the lawsuit American Baptist Churches v. Thornburgh (known as “ABC”) was settled, and the government agreed to provide new asylum hearings. All Salvadorans and Guatemalans present in the United States before a set deadline became entitled to an asylum interview.

These legal victories have continued to secure asylum seekers legal rights. When, in the early 2000s, the Bush administration claimed that Orantes interfered with its ability to remove Salvadorans under the terms of a harsh 1996 immigration law, the court again ruled against it. In 2014, a federal court ordered President Barack Obama’s DHS to allow certain lawyers to meet with detained unaccompanied minors who fled violence in El Salvador to ensure they had a chance to seek asylum.

Today, a majority of the public continues to support the right of Central Americans to seek asylum in the United States. And yet the current administration has attempted, time and again, to circumvent these protections. Its “Remain in Mexico” policy, also known by its Orwellian title, “Migrant Protection Protocols” (MPP), places those protections out of reach by sending asylum seekers to Mexico to await their hearings. Moreover, the policy potentially violates U.S. legal prohibitions against the return of asylum seekers to countries where they face threats to their lives and liberty. In Mexico, returned migrants have already faced violence, kidnappings, rape and privation.

By removing asylum seekers from U.S. soil, Trump is undermining the key protections of the law — and endangering people’s lives. He is going one step further than previous administrations that interdicted boats in the water, particularly those bringing Haitians, to keep people from making asylum claims.

There are two lessons here. First, advocacy for protecting human rights can produce lifesaving protection. That is what we see with the Orantesand ABC cases. Second, even when advocates are victorious, they may face harsh counter-responses by administrations driven by restrictionism and nativism. Moreover, despite legal wins, in the 1980s and 1990s, the number of Central Americans deported was high, and the asylum grant rate low.

Advocates fighting today’s battles can and should draw upon the successful arguments and strategies of the past — and expand upon them by pushing for humane treatment for all, limits to detention and continued access to work authorization for asylum seekers. Like the grass-roots movements of the 1980s, immigrants, their advocates and the American public have already risen up to protest the humanitarian crisis that has resulted from today’s policies. Although the fate of some of these policies rests in the hands of the courts — where Trump’s most recent asylum ban has already been challenged — the history of U.S. asylum policy offers a powerful reminder that persistent advocacy for the protection of human rights can win.