Although he rarely left London, James Petiver ran a global network of dozens of ship surgeons and captains who collected animal and plant specimens for him in far-flung colonies. Petiver set up a museum and research center with those specimens, and he and visiting scientists wrote papers that other naturalists (including Carl Linnaeus, the father of taxonomy) drew on. Between one-quarter and one-third of Petiver's collectors worked in the slave trade, largely because he had no other options: Few ships outside the slave trade traveled to key points in Africa and Latin America. Petiver eventually amassed the largest natural history collection in the world, and it never would have happened without slavery.

Petiver wasn't unique. By examining scientific papers, correspondence between naturalists, and the records of slaving companies, historians are now seeing new connections between science and slavery and piecing together just how deeply intertwined they were. "The biggest surprise is, for a topic that has been ignored for so long, how much there was once I started digging," says Kathleen Murphy, a science historian at California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo who's writing a book about the topic. She adds, "There's a tendency to think about the history of science in this—I don't want to say triumphant, but—progressive way, that it's always a force for good. We tend to forget the ways in which that isn't the case."

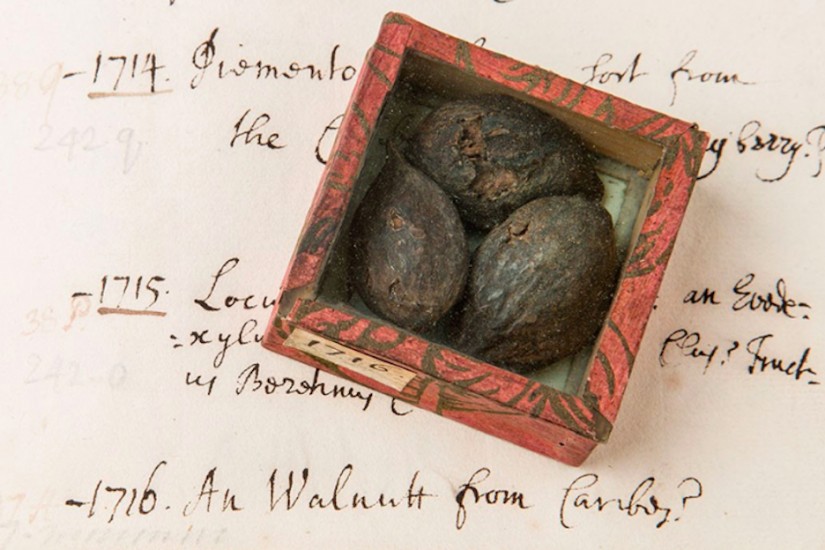

Those connections aren't just ancient history. Thousands of specimens collected through the slave trade still reside in places such as the Natural History Museum in London, and they're still used in genetic and taxonomic research. Yet few people using the collections know of their origins.

All of which casts an uncomfortable shadow on what's often viewed as a heroic era in science. "We do not often think of the wretched, miserable, and inhuman spaces of slave ships as simultaneously being spaces of natural history," Murphy writes in The William and Mary Quarterly. "Yet Petiver's museum suggests that this is exactly what they were."