“It may be well to say at the outset in this case that a great deal of misunderstanding would be avoided in abortion matters if they were considered in the light of the fact that an abortion is not necessarily, in and of itself, an illegal procedure or act,” stated the California Court of Appeals decision in People v. Ballard in 1959. “In other words, not all abortions are illegal.”

Sixty-five years later, in the wake of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022), 14 states have banned abortion, while others have imposed early, previability gestational bans that prohibit abortion before many even know they’re pregnant. In the wake of the 2024 election, more bans may follow.

While these antiabortion laws include legal exceptions designed to protect pregnant people’s health and safety, they have actually led us through a minefield of legal wrangling. Rather than clarifying the law to leave room for lifesaving measures, the distinct interpretations of legislators, law enforcement, and physicians and their confusion over where the line between preserving health ends and preserving life begins have complicated medical care and put pregnant people at greater risk.

This isn’t the first time this has happened. In 1850, the same year it was admitted as the 31st state, California criminalized abortion. The act punished anyone who “procure[d] the miscarriage of any woman then being with child” through the use of any medicine or instrument. However, the law did not apply to any physician “who in the discharge of his professional duties” saw it necessary to induce a miscarriage to save a patient’s life. In 1935, the law was amended to punish anyone who induced a miscarriage of a pregnant woman “unless the same is necessary to preserve her life.”

While the laws differ slightly, both indicate that abortions were permissible to save the pregnant woman’s life. Furthermore, the 1850 California law was unique in its provision exempting physicians. Ostensibly, these two laws are antiabortion; however, the original could also be read as a law concerned with protecting patients’ safety in an era when the medical field was organizing and professionalizing and California was far from the epicenter of professional medicine on the East Coast.

Today, similar exceptions are often included in abortion legislation. For example, Texas’s abortion law provides an exception to the total ban when a licensed physician, “in the exercise of reasonable medical judgment,” believes that the pregnancy “places the female at risk of death or poses a serious risk of substantial impairment of a major bodily function.” On the surface, these exceptions seem reasonable and simple enough. If fact, in the wake of Dobbs, antiabortion conservatives have bristled at commentary on abortion “bans” and have pointed to exceptions written into the law to indicate that abortions are still legal in the event of life-threatening emergencies. However, history shows that, in practice, the line between protecting a pregnant person’s life and protecting a pregnant person’s health has not always been clear.

In 1938, a British trial captured the attention of physicians on both sides of the Atlantic. Licensed physician Alec Bourne performed an abortion on a 14-year-old rape victim because he believed that “the continuance of the pregnancy would seriously damage—possibly irreparably damage—the girl’s health and thus her life” (emphasis mine), violating the law that banned all abortions with no exceptions. During his trial, Bourne justified the procedure based not on a direct physical threat to the girl’s life but rather on an assessment of the quality of life that she would have as a rape survivor and teenage mother of an illegitimate child. When the jury found Bourne not guilty, other places with abortion laws that provided exceptions only in relation to life, like California, also began allowing abortions for looser justifications based on health.

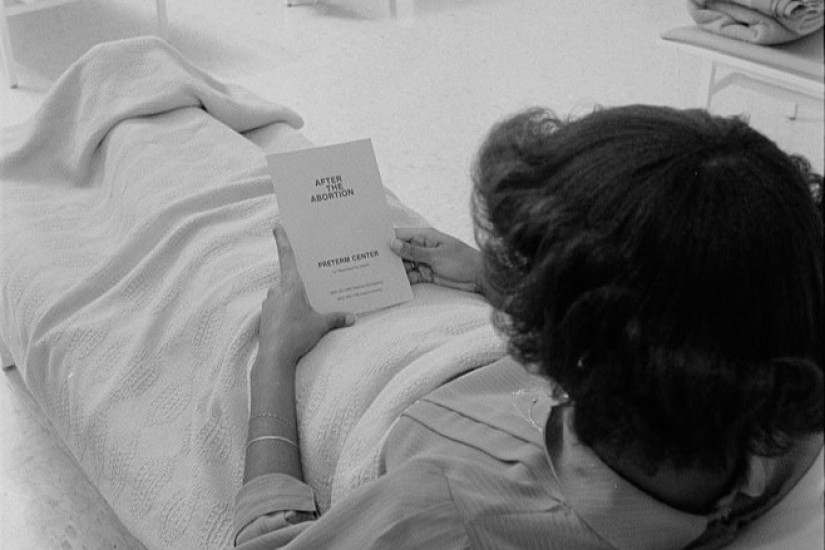

As historian Leslie J. Reagan has explained, legal abortions based on health were an area where women of means had some room for, and power to, negotiate their “legal” abortions. Women would approach their private physicians and express their desire to terminate the pregnancy, and the physician would perform that procedure in their own medical office or—increasingly after the 1930s—in a hospital. Excessive vomiting, suicidal ideation, and excessive nervousness were all justifications that physicians used for terminating a pregnancy. From the 1930s onward, this was a valuable loophole that gave women of means some agency, and for years, this practice worked well enough. Yet, as I argue in my book, a belief that therapeutic abortion exceptions were being “exploited” during the 1930s and 1940s led to the creation of new hospital committees to oversee therapeutic abortion decisions in the 1950s and 1960s.

The rise of these committees changed the procedures surrounding legal abortions dramatically. Rather than an individual physician deciding whether their patient needed an abortion, a hospital committee would decide. Other scholars of abortion, like Carole Joffe, have found “inherent unfairness” in therapeutic abortion committees’ decisions. Committees, usually composed of physicians and psychiatrists who practiced at that hospital, tended to rule in favor of well-connected women or denied requests to save spots for their own patients in their hospitals’ unofficial quotas. Aside from internal hospital machinations, there was also no uniformity across hospitals in terms of how they applied state abortion law.

When rubella swept across California from 1963 to 1965, for example, the state board of medical examiners investigated three separate hospitals for their handling of rubella-related abortion cases. Though rubella isn’t fatal, it has devasting effects in utero. A rubella infection during pregnancy can cause miscarriage. A successful birth can result in a baby born with congenital rubella syndrome, which can cause cataracts, blindness, deafness, heart defects, or intellectual disabilities. In providing abortions to pregnant women who contracted rubella, staff and physicians at hospitals at this time knew that they were technically violating the law in their handling of these cases but explained they were following the recommendations of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

The shifts in abortion law from justifications for life, to health, and back to life illustrate a blurry line and gray area that physicians exploited for their own purposes, and for their patients.

In June 1957, a woman approached Dr. Francis Edgar Ballard for an abortion at his office in Reseda, California. According to the trial documents, she was desperate for an abortion because her husband “had no access to her” in the preceding months and could not have been the father of her child. Ballard—a well-regarded and highly trained physician—performed her abortion, and later, one for another woman. He was found guilty of performing an illegal abortion on both counts.

In appealing the judgment and denial of a new trial, Ballard’s counsel claimed that there was insufficient evidence to prove that the abortion was illegal, as the prosecution had failed to prove that the abortion was not necessary to preserve the woman’s life. If the prosecution could not prove that the abortion was not necessary, then Ballard could not be found guilty of violating the law. The court agreed, deferring to physicians’ expertise and recognizing that appearances of health did not mean that someone could not be in danger. They wrote: “Many people walk, without assistance, into hospitals and doctors’ offices to have operations performed that are necessary to preserve and save life. Further, it is not a rare occurrence for a person who has gone to a doctor’s office in apparently reasonably good health, only to learn from the doctor that he is afflicted with a fatal disease.” In a later discussion of the law itself, the court of appeals further stated, “Surely, the abortion statute does not mean by the words ‘unless the same is necessary to preserve her life’ that the peril to life be imminent.”

A decade after Ballard’s appeal, in 1969, abortion came before the California Supreme Court in People v. Belous. Here, too, the case hinged on the meaning of the phrase “necessary to preserve life,” but the court found no clarification in common law. Contrary to Justice Samuel Alito and his attempt to write history in the Dobbs decision, abortion has been practiced in the United States since the colonial period—yet in our common law, “abortion before quickening [when a woman felt fetal movement] was not a crime.”

In looking at previous abortion cases, such as People v. Ballard, the court found that “our courts . . . have rejected an interpretation of ‘necessary to preserve’ which requires certainty or immediacy of death.” The court also was reluctant to hold the law to such a high standard considering that “a definition requiring certainty of death would work an invalid abridgment of the woman’s constitutional rights,” specifically “the woman’s rights to life and to choose whether to bear children.” Ultimately, the court sided with a humane, rights-focused jurisprudential tradition that recognized that pregnancy was not a health-neutral event but rather one that had dramatic implications for a woman’s life, health, and future childbearing.

In Belous, the California Supreme Court found the state’s abortion law “void for vagueness” and highlighted some of the problems with how these laws have been structured. Beyond the vagueness and slippery slope between life and health, the court recognized a problem with physicians being responsible for deciding when abortions were legal but also being punished if their decision was found to be “wrong.” According to the court, “the doctor is . . . delegated the duty to determine whether a pregnant woman has the right to an abortion and the physician acts at his peril if he determines that the woman is entitled to an abortion.” If the physician’s decision to terminate the pregnancy is found to have been in error, it is the physician who is subject to criminal prosecution. Under the structure of this law, the physician is not impartial. Rather, the physician has “a direct, personal, substantial, [and] pecuniary interest” to deny the procedure.

The problem with this law, according to the court, was the potential for complete deprivation of a woman’s right to abortion since the state “in delegating the power to decide when an abortion is necessary, has skewed the penalties in one direction: no criminal penalties are imposed where the doctor refuses to perform a necessary operation, even if the woman should in fact die because the operation was not performed.”

As a historian of public health and law, I find reading the court’s 1969 rationale for Belous today eerie, unsettling, and prescient of the abortion cases now coming before the courts. In Zurawski v. State of Texas (2024), the plaintiffs’ complaint argued that they and “countless other pregnant people have been denied necessary and potentially life-saving obstetrical care because medical professionals throughout the state fear liability under Texas’s abortion bans.” Given the hostile antiabortion landscape, it isn’t surprising that physicians and hospitals are afraid of providing abortions in Texas. Should these hospitals or medical professionals decide that a woman is entitled to an abortion, they, in the words of the California Supreme Court in Belous, “act at [their] peril” and potentially open themselves up to criminal or civil action.

In 1969, four years before Roe v. Wade, and 55 years before write this, the California Supreme Court foresaw what we’re witnessing in places like Texas today. Bans don’t prevent abortions. They dehumanize those seeking the procedure by forcing them to procure them illicitly, in less-than-safe-or-ideal conditions, or they subject these persons to the indignity of begging for medical care at their most vulnerable moments. Nevertheless, when it comes to abortion, it seems like we continuously refuse to learn from lessons of the past.