Nearly everything we thought we knew about Robert Johnson was wrong. The biographical information that historians had gathered about the King of the Delta Blues Singers, the Grandfather of Rock and Roll, an inspiration to Muddy Waters, Bob Dylan, and the Rolling Stones? The guy from Mississippi whose face was on a postage stamp?

Almost all of it was wrong.

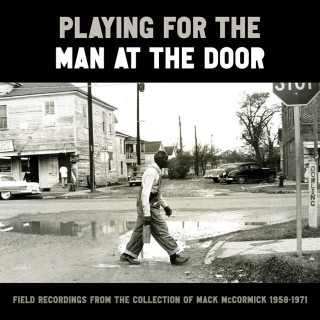

And I had the evidence in my hands: a secret manuscript about Johnson’s life found in the archive of Houston folklorist and record producer Robert “Mack” McCormick. This wasn’t just any archive. At the time, it was one of the most sought-after collections in the country—the Library of Congress wanted it, and so did the Smithsonian and the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Rock star Jack White was interested in it, as were Austin’s Dolph Briscoe Center and San Marcos’s Wittliff Collections. The archive had once filled almost every corner of Mack’s home—dozens of file drawers and boxes crammed with tens of thousands of documents, photos, and recordings. Mack’s computer was full of still more files—manuscripts, plays, interviews. The archive was so vast that Mack gave it a name: the Monster.

Mack had died just a few months before, and now I was reading a manuscript he had worked on for almost fifty years—a book that countless music fans had been waiting to read for decades. Not only had Mack never published it, he had apparently never even shown it to anyone. I felt like I was reading one of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Mack was an evocative, literate writer, and in these chapters he vividly re-created the American South of the thirties, the place and time when Johnson wrote and performed the songs that made him famous. He had even talked to people who had met the elusive Johnson—a man mythologized as having sold his soul to the devil to become a virtuosic guitarist—and who remembered things Johnson had said. I was transfixed.

But the more I read, the more confused I grew. Some passages contradicted previous things Mack had written. Others seemed to defy common sense. Still others were a little too literate.

I was baffled. Mack and I had been friends, in a way. Over the course of nearly a decade and a half, I had spent countless hours with him, much of it in late-night conversation, talking about his penchant for solitude, his writing, his ability to solve seemingly unsolvable mysteries—and his inability to finish this book. We spoke of his love for big band jazz, barrelhouse piano, and the poems of Emily Dickinson, a fellow lonely recluse who still managed to find beauty and hope in the world. I liked to think I knew Mack as well as anyone did. And yet, as I pondered the evidence in front of me, I was starting to think I didn’t know him at all.