One of the more comprehensive engagements with Davis’s ideas can be found in Ibram X. Kendi’s award-winning Stamped at the Beginning (2016), which uses her life to understand the past fifty years of the struggle against racism. And yet Kendi misreads Davis’s politics to explain his own ideas. Kendi and Davis share “antiracism” as a political objective, but they mean vastly different things by that word. For Kendi, racism is the product of errant public policies that produce disparities in social, political, and economic life. Accordingly, he sees the resolution of those disparities in “antiracists” taking electoral power so that their ideas can guide public policy, eventually turning them into “common sense.” But this solution depends on the essentially liberal assumption that changing ideas, without changing the structure of society, is the way to social transformation.

For Davis, by contrast, the root of the problem in American society is not racism but capitalism. Racism is central to the function of capitalism because it divides those who have the greatest interest in fighting it—including working-class and poor white people. Undoubtedly, capitalism makes life harder for those who are not white. But in Davis’s view, “antiracism” means developing a political strategy for changing everything, not just ascending to positions of power in the existing structure. When the Nation of Islam publication Muhammad Speaks asked its readers in Harlem in 1971 to submit questions for Davis, a number of them asked why she was a Communist. She answered them in an article she wrote for Ebony while she was jailed in California. “I am a Communist because I am convinced that the centuries-old suffering of Black people cannot be alleviated under the present social arrangement,” she wrote. “Capitalism cannot reform itself. Black people more than any should understand the truth of this statement.”

Davis eventually left the Communist Party, but not her belief that capitalism is at the root of oppression and exclusion in American society. It is a belief that has animated her activism and organizing as a prison abolitionist. She was involved in the establishment in 1997 of the prison and police abolition organization Critical Resistance. She also returned to the classroom, going on to teach in the history of consciousness program at the University of California at Santa Cruz for fifteen years (this after Reagan said, in 1970, that she would never teach in the California system again). In 2018 Davis donated to Harvard her enormous collection of personal papers, reflecting, in her words, “fifty years of involvement in activist and scholarly collaborations seeking to expand the reach of justice in the world.”

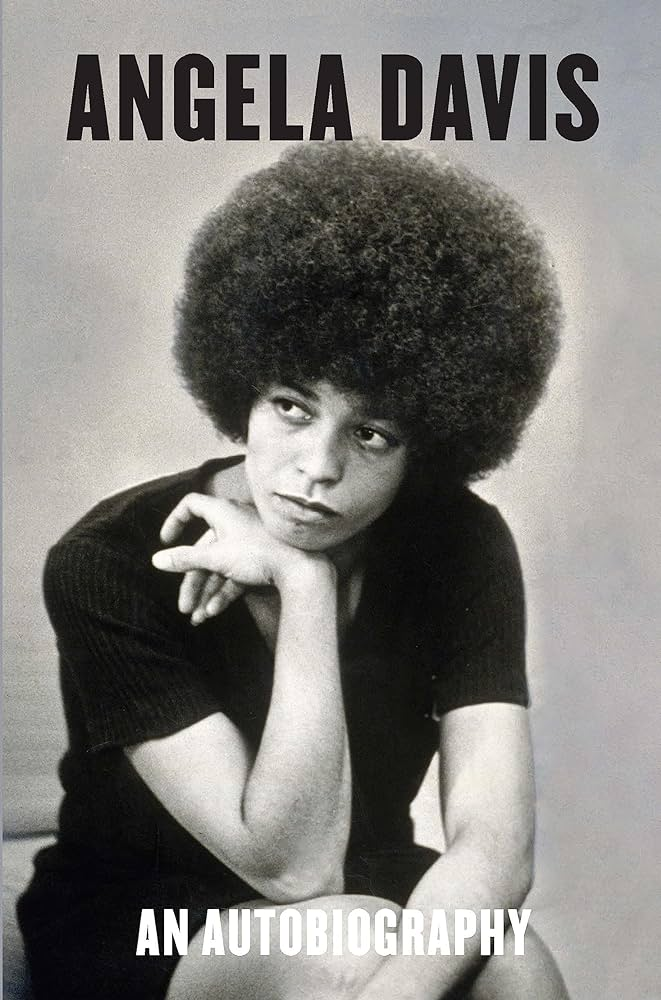

The power of An Autobiography lies in Davis’s understanding of both the tremendous forces assembled against her generation’s dreams of a new society and the ideas and actions of her cohort that stalled their forward momentum. She distills how male supremacy undermined the leadership of Black women and introduced authoritarianism and intolerance into more general debates over the politics, strategy, and tactics of the movement. Today, the struggle for Black liberation has taken new form and exists in an altogether different context, but the endless assault on Black life continues to make that pursuit necessary.