Some of the rhetoric aimed at Tyler echoes what House Democrats are leveling at President Trump. On Sunday, House Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam B. Schiff said allegations that Trump pressured Ukraine to investigate Joe Biden’s son may make impeachment inevitable. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi also sent a letter to Republicans and Democrats that demanded more information from the director of national intelligence about Trump’s interactions with Ukraine, but did not use the I-word.

When John Tyler faced impeachment 177 years ago, it was the Whigs who decided to create an investigative committee headed by a respected elder statesman, former president John Quincy Adams, who had become a Massachusetts congressman.

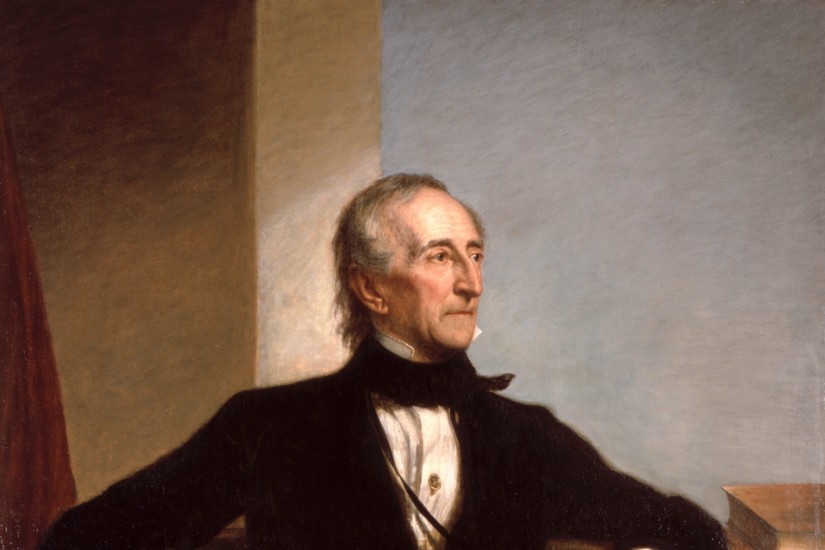

John Tyler was the first vice president to succeed to the presidency in April 1841 when William Henry “Old Tippecanoe” Harrison died after just one month in office.

The 51-year-old Tyler, a former Democratic U.S. senator from Virginia, had only recently switched to the Whig Party. As president, he began vetoing so many bills passed by Congress that the Whigs kicked him out of their party. Mobs of angry Whigs protested in front of the White House.

The anger boiled over on the House floor, where Rep. Edward Stanly of North Carolina got into a fistfight with Tyler’s best friend, Rep. Henry Wise of Virginia. Stanly complained of Tyler: “He lies like a dog.”

The president was aware of the discontent in Congress. He wrote a friend, “I am told that one of the madcaps talks of impeachment.” That “madcap” was Botts, who on July 11 gave notice of his plans, warning, “If the power of impeachment is not exercised by the House in less than six months, ten thousand bayonets will gleam on Pennsylvania Avenue.”

Eleven days later, Botts formally introduced a petition to impeach Tyler “on the grounds of his ignorance of the interest and true policy of this government, and want of qualification for the discharge of the important duties of President of the United States.” The House voted to table the proposal for the time being.

Botts separately specified his charges against Tyler. Among them: “I charge him with the high crime and misdemeanor of endeavoring to excite a disorganizing and revolutionary spirit in the country, by inviting a disregard of, and disobedience to a law of Congress.” He charged the president with “abuse of the veto power, to gratify his personal and political resentment,” and of being “utterly unworthy and unfit to have the destinies of this nation in his hands as chief magistrate.”