Americans today seem to believe that we live in especially exhausting political times. But the rhythms of our moment—pandemic, protest, pandemic, election, insurrection, pandemic, invasion of Ukraine—have nothing on the Truman era. Between April, 1945, when Franklin D. Roosevelt’s death thrust Harry S. Truman into office, and January, 1953, when Truman handed the Presidency to Dwight D. Eisenhower, the war in Europe ended, Hitler killed himself, the United States dropped two atomic bombs on Japan, the Cold War began, the state of Israel came into being, the Soviet Union developed its own nuclear weapons, China underwent a Communist revolution, the West created NATO, the world created the United Nations, and the Korean War began. One could go on.

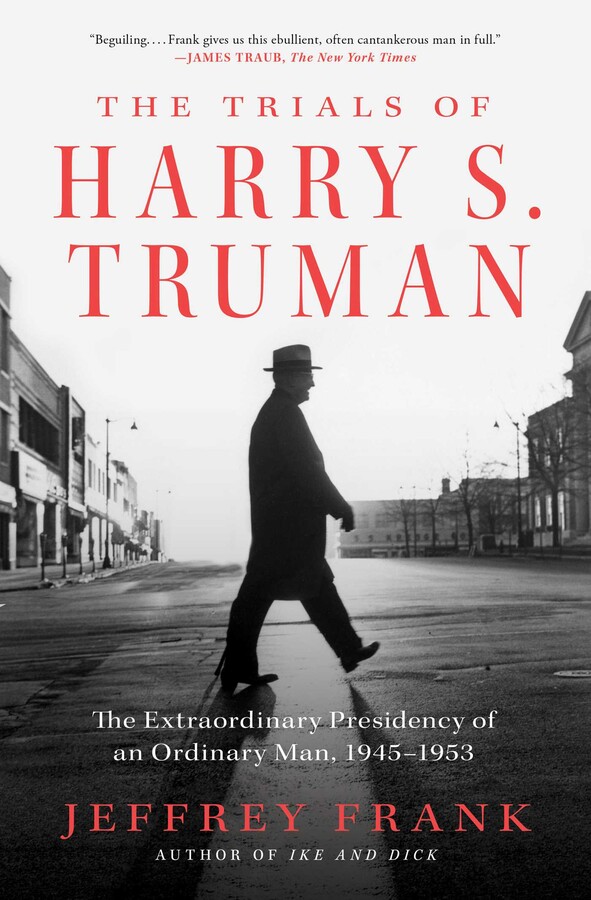

How much Truman shaped these events, and how much he was buffeted by them, is the puzzle at the heart of Jeffrey Frank’s new book, “The Trials of Harry S. Truman: The Extraordinary Presidency of an Ordinary Man, 1945-1953” (Simon & Schuster). Truman was the ultimate accidental President, a pipsqueak senator from Independence, Missouri, who had been Vice-President for less than three months when Roosevelt died. Once Truman assumed office, global events seemed to proceed according to their own logic and momentum. Truman inherited daunting challenges, and he borrowed other men’s visions in order to meet them. His own accomplishments occurred somewhere in between.

Truman acknowledged that he didn’t have much choice about whether to drop the bombs. “As a practical matter,” Frank notes, the decision “had been made for him.” Truman’s greatest foreign-policy triumph, the European Recovery Program, is credited to the military giant and Secretary of State George Marshall; we don’t call it the Truman Plan. As President, Truman was accused of “losing” China, but China was, of course, never really his to lose. And it was Senator Joseph McCarthy, more than Truman, who defined the political tenor of the era.

Perhaps Truman’s most significant act as President was his decision to enter and then stick with the war in Korea. Although that conflict was never the political disaster that Vietnam turned out to be, it killed millions, often with shocking brutality. The South was effectively recaptured in the first few months; the long, blood-drenched impasse that ensued accomplished little. On the home front, Truman’s dream of achieving universal health care languished as well. After a bruising battle with the American Medical Association and the Republican Party, he ended up more or less where he started.