What makes Reed a quintessentially New York artist? Is it his profound mutability or the consistent inspiration the city provided him with? (“New York City man, you blink your eyes and I’ll be gone”; “I’m a Coney Island baby now”; “New York City lovers, tell it to your heart.”) Could it be his blunt attitude, his capricious moods, or his notorious hostility toward the press? Or is it just that he stayed there—within city limits or nearby, in New Jersey and Long Island—for most of his life? For Rolling Stone critic Will Hermes, it is a little of each of these things, but above all it is his participation in a conspicuous scene, or series of scenes, that shaped and branded the city’s culture half a century ago.

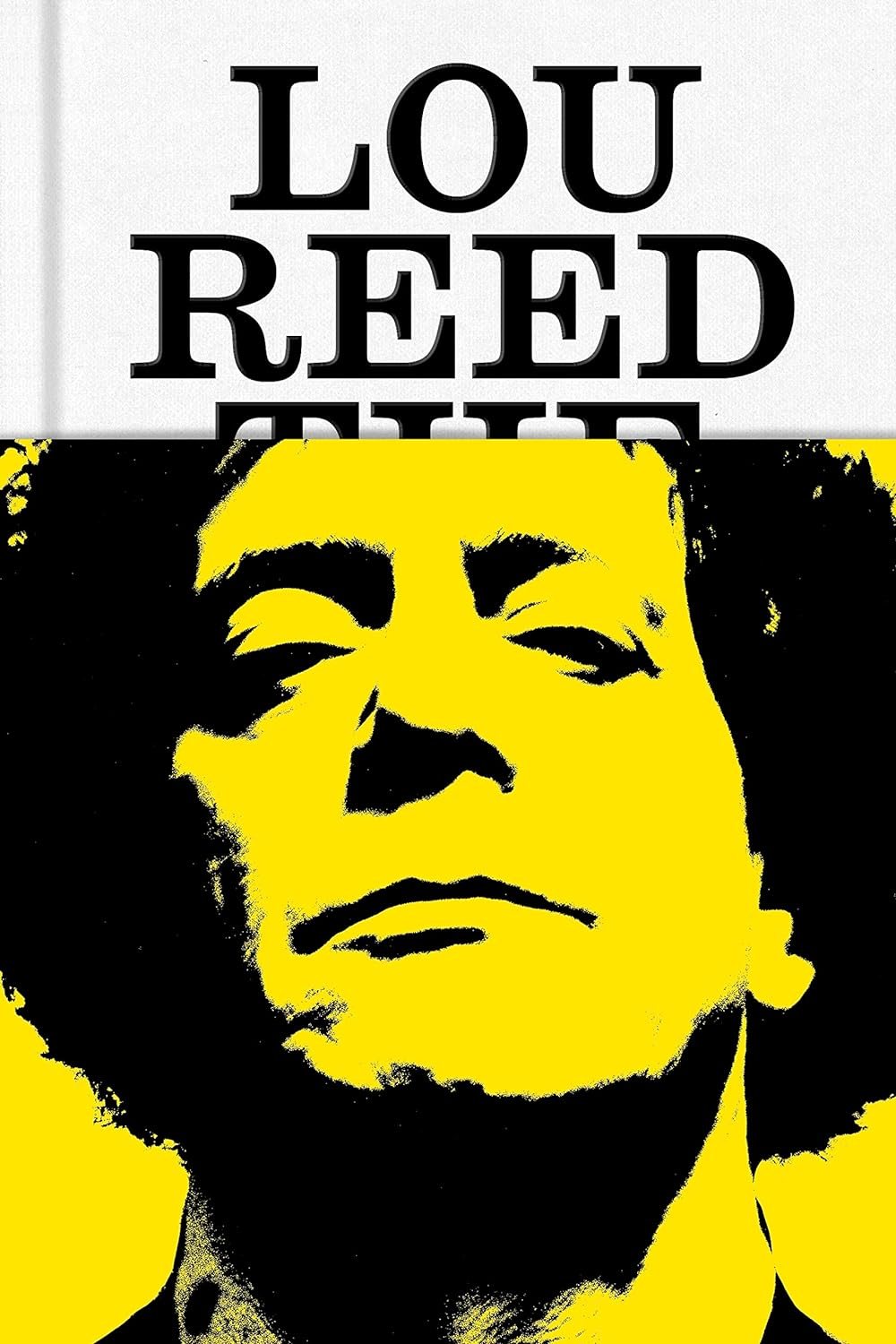

“Lewis Allan Reed . . . was a mirror of post–World War II New York City arts writ large,” Hermes contends in the introduction to his new biography, Lou Reed: The King of New York. Reed said he was a New York City man, and Hermes promises a New York City book, with new material drawn from Reed’s archives at the New York Public Library and a suitably scholastic approach. But Hermes is so smitten with the era in the city’s history that brought Reed to prominence that he risks shoehorning Reed into narratives of political progress and social import that the artist, on most days, emphatically eschewed. Reed did not preside over the city, nor did he reflect its shiniest, bravest qualities, at least not most of the time. He was, rather, something of a peripheral figure, no matter how famous he became, and this was by design. He was a reinventor, marketer, and anonymizer of the self.

The Velvets’ sneering rejection of hippie sentimentality was only the first of many artistic rebellions for Reed, who went on to put out nearly two dozen solo studio albums of vastly different, even contradictory styles: glam rock, pure dissonant noise, a collaboration with Metallica—he tried it all and succeeded at some of it. He also said it all. Whether he wrote from his own experience or from sketches of real and imagined others, he had an insouciant flair for character. His proliferating personas made him a particularly difficult subject to take at his word, both in interviews and song.