[Editor’s Note: Over the course of 2022 and 2023, New American History Executive Director Ed Ayers is visiting places where significant history happened, and exploring what has happened to that history since. He is focusing on the decades between 1800 and 1860, filing dispatches about the stories being told at sites both famous and forgotten. This is the second installment in the series.]

I'm writing this as the sun comes up on a Sunday morning in March. Spring is arriving and we are finally ready to head out on our travels in earnest.

We spent much of yesterday working our way through all the technical systems of Bertha. We de-winterized her, sanitized all the water lines, figured out how to fill and flush the tanks, turned on the water heater, got the refrigerator running, and so on. It was complicated and frustrating, since we were trying to figure out so many things at the same time. Fortunately, our son Nate and his wife Rachael were here to assist (or rather, we were there to assist them.) Their dog, Beck, helped by warming up the passenger seat. We watched many videos and scratched our heads over cryptic diagrams.

We are heading to South Carolina, where we expect it to be warmer, spring a little farther along than it is here. We will head down U.S. Rt. 29, an undulating four-lane road near our home that will take us all the way to Greensboro, North Carolina. We have driven it many times and know that it’s less intense than either of the interstates that could take us south, I-81 and I-95. Abby and I are not quite ready to weave among the 18-wheelers.

We purchased carbon offsets to compensate for the environmental impact of our trips for the next 18 months, but I still feel guilty when I pull up to the diesel pump. The engine is sophisticated and actually cleaner than gasoline, but still . . . I tell myself that we’re making much less of an impact than we would if we flew and stayed in hotels and rentals. The campgrounds where we stay offer water, electricity, and sometimes plumbing, so we’re not using many resources there. We have a solar panel to charge our batteries for when we “dry dock.”

One advantage of driving a house is that you’re always home for lunch. We stopped outside Charlotte, North Carolina, and after looking at the usual array of fast-food places, decided to have a PB&J at our table inside. We ate in the parking lot of a Target, where we looked for a tire gauge and some bungee cords to secure some drawers and doors that kept sliding open, loudly and alarmingly, on exit ramps.

We drove farther than we thought we might. Bertha is comfortable and has enough power to keep up with trucks. Our destination is Beech Island, South Carolina, which sounds as if it would be on the coast, but is in fact on the Savannah River, across from Augusta, Georgia.

Towards the end of the day, we pull into a nice KOA campsite that Abby has located. Back in our tent-camping days, we used to joke about KOA standing for Kamping On Asphalt, but we’re growing to appreciate a level parking spot and full connections. This particular one is decorated with a gnome theme, adding a touch of whimsy. We have a microwaved meal that’s pretty tasty, stroll around a bit to look at the other RVs, and then settle into our new home with all the amenities operational for the first time. We watch an episode of a Netflix series we started back home. It’s not unpleasant at all.

The next morning we visit the home of one of the least appealing people in my story: James Henry Hammond. On what proved to be the eve of the Civil War, in 1858, Hammond moved into a new home, Redcliffe. It was not a working plantation but rather a showplace for the wealth Hammond had accumulated from his other nearby plantations, where hundreds of enslaved people labored. Hammond was proud of his wealth and advanced farming techniques, using marl from shells to add phosphate to the sandy soil. He had married into the prominent Hampton family of South Carolina.

Abby and I, driving Bertha down a dusty road, arrived a bit late for the tour we hoped to take. Fortunately, a small group was seated on benches under a large tree, listening to a ranger orienting them to the site. Everyone was white, including the ranger; a mother, father, and four children composed most of the group. School was out of session that week, but it’s possible they were homeschoolers. Everyone wore a Christian T-shirt of one form or another. Another adult couple seemed to be with them, and one young man from Oregon was there by himself.

We listened as the young woman explained some hard things about Hammond. He had not only held people in slavery, but had sexually abused women he enslaved; several bore children by him. The young people — one boy and three girls in their early teens — seemed interested and not disturbed by the talk. They asked good questions, and the interpreter answered them expertly and appropriately.

I was heartened by the conversation, for I have been involved in many similar exchanges. Abby and I live about ten miles from Monticello, the home of Thomas Jefferson, and travel a road every day that he would have taken to his other plantation near Lynchburg. It is actually called Old Lynchburg Road. Jefferson’s relationship with Sally Hemings has been the topic of discussion, debate, research, and interpretation for the 42 years we have lived in Charlottesville. I have participated in those conversations over the years and I’m proud to see the progress Monticello has made.

But the work has been hard, and is not to be taken for granted. Another historic home with which I have worked — Montpelier, the home of James Madison, author of the Constitution — has been the object of great division and controversy recently. Several years back, they installed an important exhibit — “The Mere Distinction of Colour” — that won great attention and praise; I was honored to appear in it.

Montpelier also won praise for including members of the descendant community of enslaved people as equal board members. Less than a year later, though, the board of Montpelier fired longtime and much-admired staff members after they resisted board efforts to constrain descendant participation. After a great deal of negative publicity, the board and the descendant community reached an agreement. I hope their important work can continue.

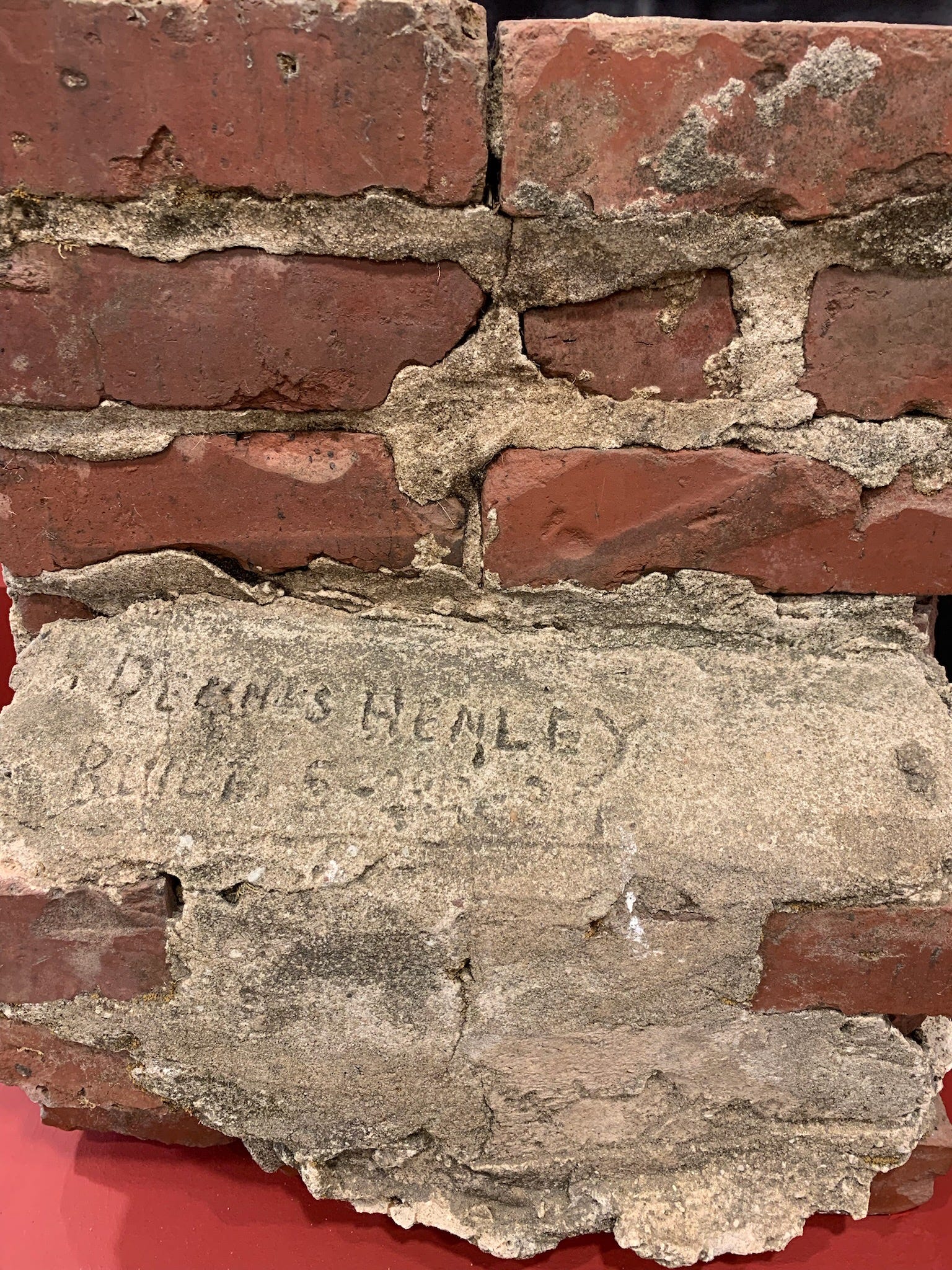

With that background, I am eager to see how other places are dealing with the facts and consequences of slavery. Our experience at Redcliffe was encouraging. The visitors center held small but forthcoming displays about the life of enslaved people and their descendants on the land. One exhibit devoted to “African American Families before and after Emancipation” showed pictures of individuals, told their stories, and presented a piece of mortar in which Dennis Henley, the grandson of enslaved people, had proudly written his name after building a wall generations before.

The visitor center also told the story of James Henry Hammond, famous for his defiant speeches in the late 1850s, when he declared that “cotton is king” and that every society had “mud-sills” — unskilled laborers who did menial work so that more refined people would not need to do it. In the South, they called such people slaves. Hammond told northerners that they also relied on their own class of white mud-sills, even if they wouldn’t admit it. He also, as the exhibit at Redcliffe showed, declared that “women were made to breed.”

Such speeches — arrogant, racist, and antagonistic — helped bring on the Civil War just three years after Hammond built his house. He would not serve in the Confederacy and would not survive the war. He died at the age of 57 after poisoning himself for years with self-administered remedies now known to be toxic.

Hammond’s house was large, dark, and echoing. It included more than 2,000 books, as well as pieces of art and statuary he had acquired on a trip to Europe. In the house, the young interpreter told of Hammond’s horrifying sexual abuse of several of his own nieces, abuse that destroyed their reputations even as he rose to become a U.S. senator. Again, the young women on the tour — about the age of those Hammond assaulted — listened intently. I was impressed, for I knew the story and found that it haunted everything about Hammond.

I chatted a bit with the young interpreter after the tour. She said that she sometimes encountered resistance and resentment when she told of Hammond’s history, but more often people appreciated her honesty. She works for the state of South Carolina, and it speaks well of her and of her employers that she is able to interpret Redcliffe in such a humane way.

Sobered and saddened by what we had seen, we clambered back into Bertha and set off for Charleston, on the trail of a different kind of history.

Denmark Vesey is everywhere and nowhere in Charleston. Vesey, a free Black man resident of the city, was accused of, and executed for, planning a slave rebellion in 1822. Historians debate whether there were indeed such plans and if so, whether Vesey was behind them, but white South Carolinians certainly believed the plot existed. So do all of those who have lionized him in the two centuries since.

The fences around many of Charleston’s fine houses, many topped by spikes, are reminders of that long-ago threatened rebellion. The house where he was long storied to have organized the rebellion is a National Historic Landmark, even though it has been demonstrated to have been built after Vesey’s death. A Denmark Vesey statue stands away from the main tourist thoroughfares. It has been vandalized with a hammer. But there are few other indications of the man or the aborted, or perhaps mythical, revolt.

The museum at the Old Slave Mart tells the story of the place created in the late 1850s to remove the slave trade from the streets. It is mainly walls of text and images, with a few artifacts, including shackles, identification tags, and a whip. The displays, put up in 2007, remain powerful, direct, and accurate. We saw visitors — most of them white — reading them with care; parents explained slavery to their children in careful but accurate language.

A 70-year old guide, with long white hair and gray eyes, told us he had ancestors stretching back 300 years, white and Black, and has people buried all over the city. He opened the back door to show us the parking lot where the holding cells, kitchen, and sick house were once located.

On the streets outside, ubiquitous carriage rides promise tours of the “Old South.” But in general the spirit of Charleston is New South, decorated with pastel shirts for men and women and restaurants with local foods in new fusions. Our Uber drivers told us the place was filling up with people from New York, New Jersey, Ohio, and California, fleeing high taxes.

Charleston’s 18th century houses do not speak of slavery in the 19th century. There is no sense that the city was majority Black before the Civil War, no way to see the presence of enslavement behind every corner. The tall monument to the fallen soldiers of the Confederacy is hidden in a pleasant park, where the tomb of Pierre Tousannt Beauregard rests. (One of our Uber drivers thought it was “Robert E. Lee, or some general.”)

A new International African American Museum will be opening later in 2022. It looks promising and exciting. We will need to return to see it — and look forward to doing so.

But as was the case at Redcliffe, there is no clear explanation of why South Carolina would act with such determination and recklessness to leave the United States. While the symbols of defiance have faded from view, nothing has taken their place except forgetfulness and polite evasion. Charleston is lovely; its role in nearly destroying the nation hidden.

The last stop on our trip was a place not many people would have chosen: the James K. Polk birthplace in Pineville, North Carolina. We arrived at opening, met by a friendly and knowledgeable young man. It is a small place, a 1960s-like brick building next to reconstructions of cabins of the sort the Polk family would have lived in early in the 19th century. Men were mowing the grass with zero-turn mowers, expertly directed.

I asked the young man what visitors showed up to the site expecting. Just as I had suspected, he told me that most people have no clue who James K. Polk was or what he did. They have no idea that he triggered the war with Mexico and went on to purchase most of what is today the nation’s western third, including California. At the time, he was the youngest man ever elected president, and yet he worked himself to death. Despite his success in his intended purpose, Polk was widely vilified. Meanwhile, the men who emerged from the war as heroes were the generals he despised and distrusted: future president Zachary Taylor and future presidential candidate Winfield Scott.

In the main house, a film made for television some years ago played on a regular basis. It was adequate, telling about the war but almost nothing about how a man such as Polk became president in the first place. The exhibits around the film were surprisingly strong, documenting life in the first half of the 19th century. I saw things I had read about but not seen before: a whale oil lamp, a saw-toothed cotton gin, an electric device for healing, a temperance pledge on rollers. On the other side of the exhibit, a few things about manifest destiny and the war with Mexico were displayed — including an impressive hat worn by General Santa Anna.

In general, a visitor would leave knowing little about Polk’s central role in acquiring much of the modern United States. Here again, the interpreters on site had been thoughtful, knowledgeable, and dedicated people. And yet the larger significance of the place remained elusive.

It occurred to me that our brief journey so far had not revealed pieces of a mosaic, but rather fragments of a shattered mirror, its pieces scattered and broken. People of good will came to these places and people of good will sustained them, but how it was that slavery had driven the U.S. to war with Mexico, and then with itself, remained beyond reach.

Abby and I returned home tired, but a bit more experienced with Bertha and with a better sense of what we might find on the next leg of our journey.