When Justice Antonin Scalia issued his scathing and bridge-burning dissent in the Supreme Court’s same-sex marriage case this summer, some observers wondered what he hoped to gain. After all, the justices in the majority had already made their decision—there was little hope of changing their minds. If anything, Scalia’s dissent, with its mocking tone and personal insults, seemed likely to alienate his fellow justices, exacerbating the already-deep divisions on the court and perhaps harming its public image. So, aside from letting off steam and repeating his well- known views, what was the point?

That question could be asked of any dissenting opinion, and it serves as the impetus for Dissent and the Supreme Court, by the distinguished legal historian Melvin Urofsky. Tracing the history of dissents from the founding era to the present, Urofsky attempts to determine what value can be found in opinions that, by definition, do not state the governing rule of law.

Until well into the twentieth century, dissenting opinions were rare, with the justices reaching unanimous results in roughly 90 percent of cases.

His conclusion is that dissents are an essential part of the “constitutional dialogue,” both within the Court and between the Court and the public, and that this dialogue is “the device by which our nation has adapted its foundational document to meet the needs” of changing times. The Constitution, in other words, is a work in progress, and dissents, like majority opinions, help determine the direction that progress takes.

The notion of a “living Constitution” is one that originalists such as Scalia wholly reject. To them, the words of the Constitution have a fixed meaning that can be ascertained only by looking to the views of the generation that ratified them. But by telling the story of constitutional law through the lens of dissenting opinions, Urofsky is able to show just how much our own understanding of the document has changed over time—and the extent to which dissents have presaged and driven much of that change.

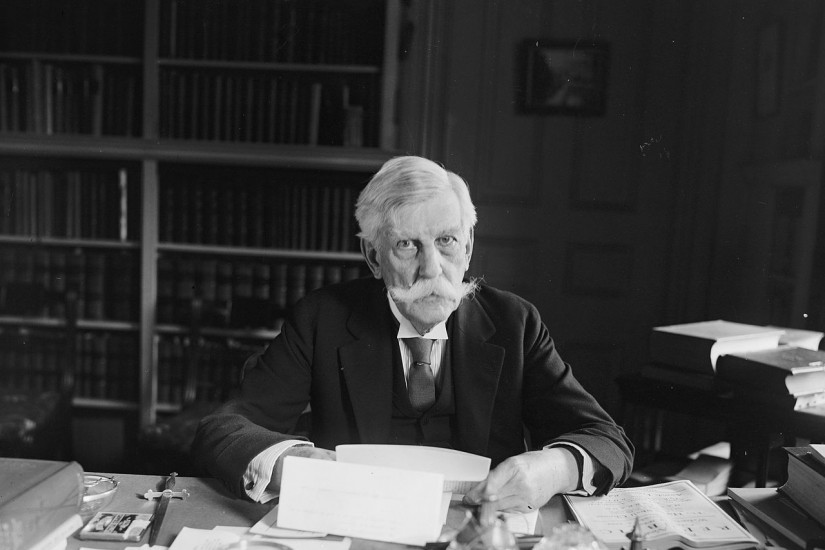

He reminds us, for instance, that Justice John Marshall Harlan’s dissent from the doctrine of “separate but equal” in 1896 laid the groundwork for Brown v. Board of Education (1954), decided more than half a century later. That Justice Louis Brandeis’s dissent in a prohibition-era wiretapping case ushered in our modern understanding of privacy law. And that Justice Hugo Black’s persistent dissents throughout the 1940s and 1950s paved the way for the Court’s 1963 ruling in Gideon v. Wainwright that states must provide legal counsel for indigent criminal defendants.