When Elites Were Revolutionary

The declaration made in Philadelphia in the summer of 1776 formally announced what would become not only the American Revolution but the Age of Revolution. In France in 1789; in Haiti in the 1790s; across Europe in 1848; culminating perhaps in Russia in 1917.

Among the features setting the American Revolution apart from those that followed, however, is that it was in many ways a revolt of the “better classes,” or the elite. While the loyalties of ordinary colonists were deeply divided, those who led the movement to divorce from Great Britain were among the wealthiest, best educated, and, especially in Virginia, landed, slave-owning men in the colonies.

A depiction of the drafting committee presenting its work to the Continental Congress in 1776 (left). President George Washington leading troops against a populist uprising known as the Whiskey Rebellion in 1795 (right).

Many of them, in fact, were deeply suspicious of “the people”—whom they referred to derisively as “the mob.” When these elite met in Philadelphia to draft the Constitution, they baked that suspicion into our political system.

Unwilling to have the people elect the chief executive, they created the truly bizarre Electoral College. Uncomfortable that the legislature should correspond to the population, they invented the Senate to counter-balance the House of Representatives in giving states—really just a set of arbitrary lines on the map—equal power.

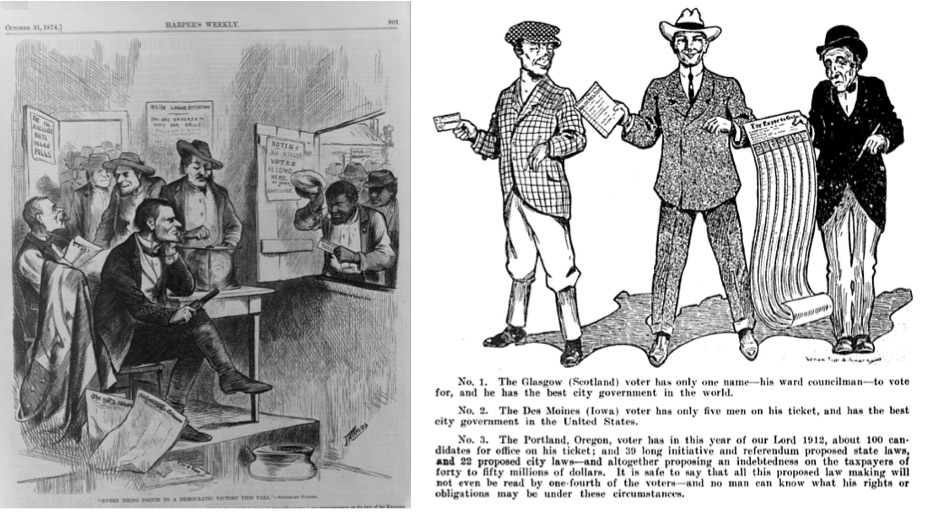

And states themselves echoed these suspicions of “the mob” by restricting the right to vote in all sorts of ways. Most infamously, Southern states made it effectively impossible for African Americans to vote between the 1870s and the 1960s. In the last several years, states controlled by Republicans, like Indiana and Wisconsin, have enacted voter restriction laws that have curtailed access to the polls dramatically.

A Harper’s Weekly cartoon depicting African Americans being denied the right to vote in 1874 by the White League (left). A 1912 cartoon mocking Oregon’s election system in which voters weighed in on a variety of proposed state and local laws (right).

In short, the United States was created and shaped by people who were not comfortable with democracy.

In a letter to the Marquis de Lafayette, George Washington wrote: “It is one of the evils of democratic governments, that the people, not always seeing and frequently misled, must often feel before they can act.”

And he was not alone in his disdain for “the people.” Alexander Hamilton would have been pleased about the sky-high ticket prices now serving to keep the riff-raff out of his namesake Broadway hit.