In the half century between the elections of Governor Reagan and President Trump, the left and the right would appear to have switched sides, the left fighting against free speech and the right fighting for it. This formulation isn’t entirely wrong. An unwillingness to engage with conservative thought, an aversion to debate, and a weakened commitment to free speech are among the failures of the left. Campus protesters have tried to silence not only alt-right gadflies but also serious if controversial scholars and policymakers. Last month, James B. Comey, the former F.B.I. director, was shouted down by students at Howard University. When he spoke about the importance of conversation, one protester called out, “White supremacy is not a debate!” Still, the idea that the left and the right have switched sides isn’t entirely correct, either. Comey was heckled, but, when he finished, the crowd gave him a standing ovation. The same day, Trump called for the firing of N.F.L. players who protest racial injustice by kneeling during the national anthem. And Yiannopoulos’s guide in matters of freedom of expression isn’t the First Amendment; it’s the hunger of the troll, eager to feast on the remains of liberalism.

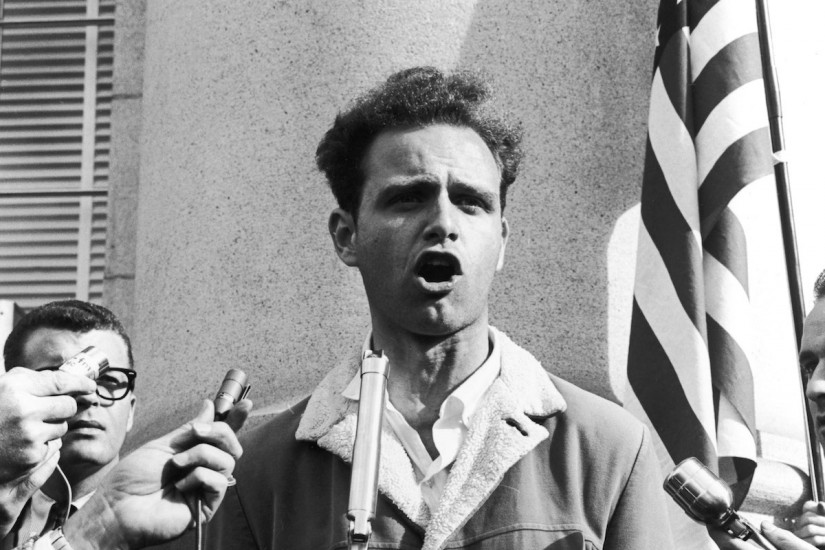

The Free Speech Movement is the taproot of a tree with many branches. In 1964, Mario Savio, a twenty-one-year-old Berkeley philosophy major, spent the summer registering black voters in Mississippi. When he got back to Berkeley that fall, he led a fight against a policy that prohibited political speech on campus, arguing that a public university should be as open for political debate and assembly as a public square. The same right was at stake in both Mississippi and Berkeley, Savio said: “the right to participate as citizens in a democratic society.” After the police arrested nearly eight hundred protesters at a sit-in, the university acceded to the students’ demands. The principle of allowing political speech was afterward extended to private universities. Without it, students wouldn’t have been able to rally on campus for civil rights or against the war in Vietnam, or for or against anything else then or since.