Americans in the second half of the nineteenth century had no sure prospect of resting in peace after death. If their bodies weren’t embalmed for public viewing or dug up for medical dissection, their bones were liable to be displayed in a museum. In some cases, their skin was used as book covers by bibliophiles and surgeons with a taste for human-hide binding.

The preservation, exhumation, and exhibition of human remains become, in the hands of the literary critic Lindsay Tuggle, an illuminating basis for a provocative reassessment of America’s foremost poet, Walt Whitman. In The Afterlives of Specimens, Tuggle aligns Whitman’s life and work with the practice of preserving and learning from cadavers or body parts during the Civil War era. She offers new insights into Whitman’s poetics of the body, both by limning the history of body preservation and by considering his development using the work of various psychologists and literary theorists, including Sigmund Freud, Jacques Derrida, and Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick.

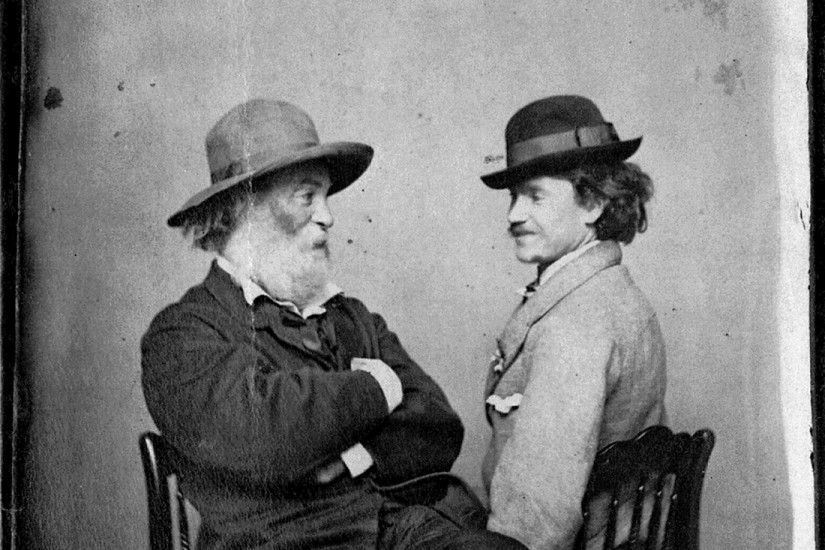

Whitman, long recognized for his candid treatment of the body and sexuality, was also the quintessential poet of disability and death. As a volunteer nurse in the Civil War hospitals in Washington, D.C., he visited, according to his own estimate, between 80,000 and 100,000 wounded or sick soldiers over the course of four years. He typically went twice a day to the hospitals, walking from cot to cot, tending to the soldiers, giving them food or small gifts, reading to them, writing letters for them, or sitting quietly by their side. Although his daily visits took a toll on him (he developed tuberculosis during the war), he got pleasure—including, it appears, homoerotic arousal—from his encounters with soldiers who stoically faced death or permanent disability.

Whitman was also inspired by the war to write new poetry. In the early spring of 1865, he arranged to publish a collection, Drum-Taps, that was delayed due to Lincoln’s assassination in April and appeared along with a sequel later that year. This volume contains the finest Civil War poetry we have. Its republication as Drum-Taps: The Complete 1865 Edition, expertly introduced and annotated by Lawrence Kramer, is most welcome. Since Whitman dispersed his war poems, often heavily edited, throughout later editions of his magnum opus Leaves of Grass, these poems have previously been available to general readers only in truncated, scattered form. Kramer’s edition of the original 1865 Drum-Taps and its sequel restores Whitman’s immediate creative response to the war that killed more than 750,000 Americans and injured at least 500,000 others—more American casualties than in all other wars combined.