JP: That reminds me of another way you talk about our relationship with the deep ocean: knowledge versus mastery. The ocean is this other realm here on earth. We had neither knowledge nor mastery of it, but then there was suddenly this possibility of knowledge without mastery. How do you think about those two categories?

MC: The Marxist paradigm for thinking about the relationship between the human and the natural world is a relationship of technological mastery. Technology captures the energy, the potential of the natural world, and turns it into a servant for good or evil. But when you’re contending with this vast force…

JP: The unmasterable sea! And in contrast to the ultimate vulnerability of the human body. You actually spend a lot of time, in really wonderful detail, unpacking the not exactly fetishistic but certainly technophilic quality of what it means for people to be geared up for undersea exploration. You seem to think that part of the appeal of these films is the gear.

MC: Absolutely. I’m trying to remember the budget for Thunderball. Maybe it’s $800,000 to shoot that amazing underwater fight scene. It’s certainly a gadget-filled wonderland. I think the fascination with technological innovation is that it enables us to engage with such an unruly environment, both emotionally and practically.

JP: Where are the other amazing filmographic breakthroughs? 20,000 Leagues under the Sea? Flipper?

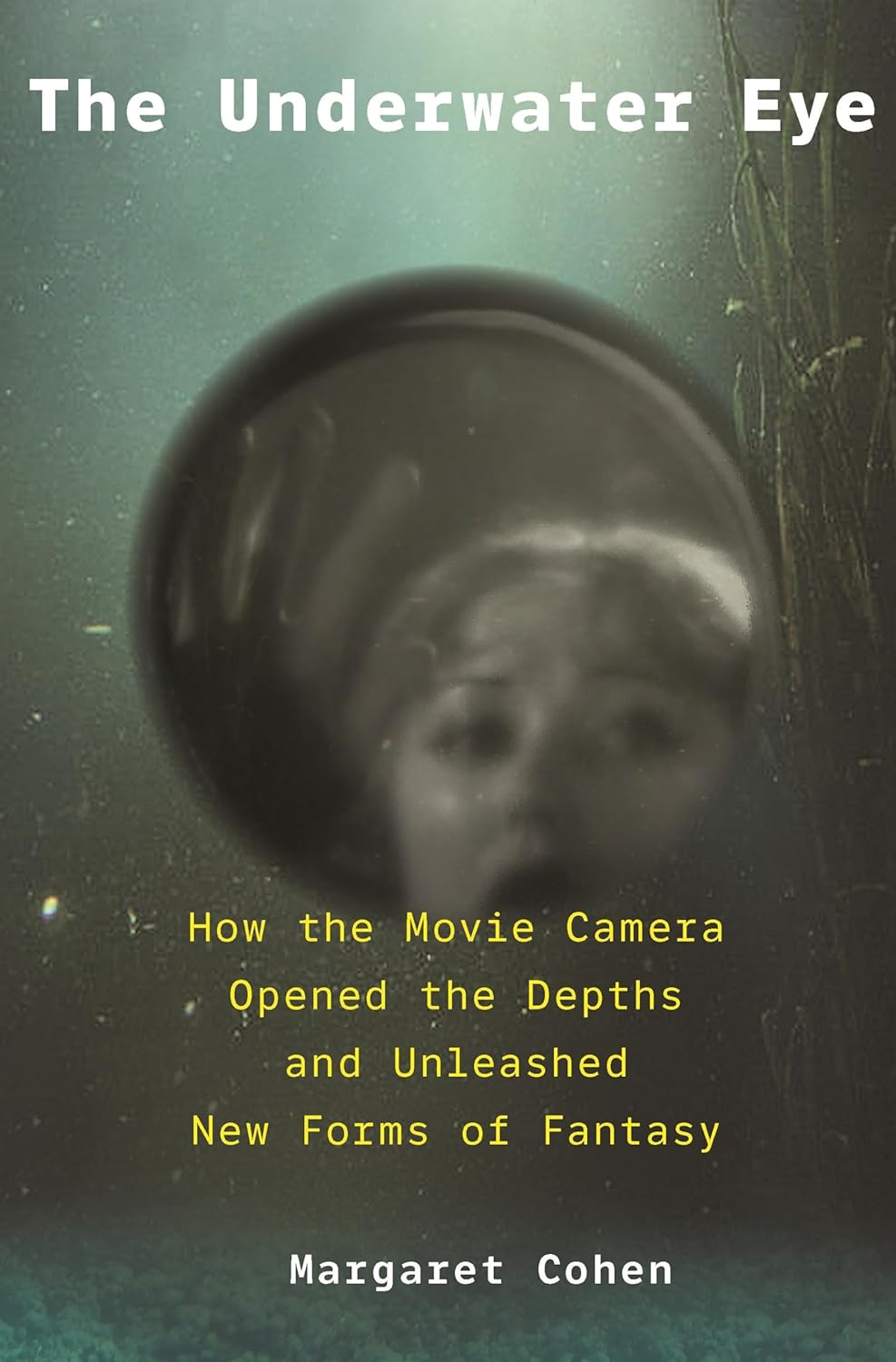

MC: I structured the book around breakthroughs, actually. So, for example, the 1916 20,000 Leagues is really quite an extraordinary film. It was filmed with the first technology for filming underwater, which was an enclosed sphere where the camera operator was enclosed in air and had the instructions coming down from the surface via voice communication. And this film featured extended underwater sequences of a length that you won’t see till Thunderball.

JP: Yeah, that funeral procession, for example, minutes long and filmed completely underwater.

MC: Oh, in the funeral procession—talk about technology! That was made using a closed-circuit breathing apparatus designed for the military during World War I, which was very dangerous. Witnessing the marvels of the sea in the first sequence, seeing sharks for the first time on film—I mean, sharks that size do not survive in aquariums. You even have the hunters and the sharks in the same frame. It’s not faked. That’s a revelation.