Frank Watlington, a US Navy engineer, was based in Bermuda during the Cold War. In the early 1950s he was covertly listening for Russian submarines and dynamite explosions through a set of hydrophones—underwater microphones—when he picked up some unfamiliar sounds. An unidentifiable noise was disrupting his fieldwork. By 1955 he identified the sounds as those of local humpback whales he had spotted swimming not too far away. Over ten years later, in 1967, when enough time had passed for the material to be declassified, Watlington decided to hand the recordings over to a trusted friend, the whale researcher and environmentalist Roger Payne, who was also conducting studies in the region. Payne then reached out to Scott McVay, another whale specialist (who had studied with the well-known eccentric cetacean neuroscientist John C. Lilly), and the two spent years analyzing the data. By running the material through an aural spectrograph that McVay accessed at Princeton University where he worked, they concluded that most certainly these whale vocalizations were unique patterns, and they likened them to “songs.”

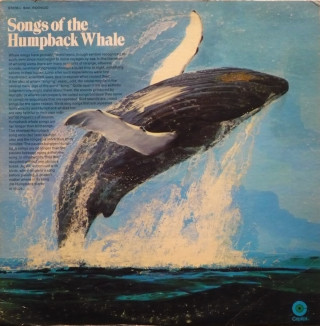

Payne and McVay sensed the affective power of these sounds and partnered with Communications Research Machines, Inc. (CRM), an independent publishing company in California, to press a limited run of LP records titled Songs of the Humpback Whale in 1970. The next year, they coauthored the article “Songs of the Humpback Whale,” which appeared on the cover of Science journal alongside visual renderings from the aural spectrograph. Each track of the LP contained long, high- and low-pitched moaning calls from between one to three whales at a time. The record’s written material was bilingual in Japanese and English to appeal to audiences potentially aware of the violence of the Japanese and American whaling industries, and included a thirty-six-page booklet urging the reader to help stop commercial whaling through sharing facts, maps, graphs, and personal narratives. Songs of the Humpback Whale became incredibly popular over the next decade. The album was reissued in English by Capitol Records, then again by National Geographicin 1979 as a flexi disc. Along with the greeting “hello” recorded in fifty-five languages, excerpts were included in NASA’s 1977 Golden Record aboard the Voyager spacecraft and later inspired a Star Trek feature film. It instigated the Save the Whales campaign, was sampled by popular and experimental contemporary musicians alike, and was even played on the floor of Congress by animal activist Christine Stevens in 1971 during a hearing on whale conservation. Due in part to such efforts, commercial whaling was officially banned in the United States by 1982.