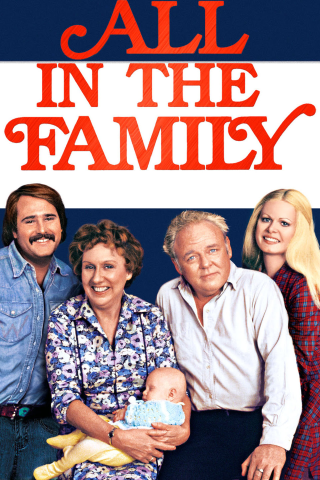

“The program you are about to see is ‘All in the Family.’ It seeks to throw a humorous spotlight on our frailties, prejudices and concerns. By making them a source of laughter, we hope to show—in a mature fashion—just how absurd they are.”

This nervous disclaimer, which was likely as powerful as a “Do not remove under penalty of law” tag on a mattress, ran over the opening credits of Norman Lear’s new sitcom. It was 1971, deep into the Vietnam War and an era of political art and outrage, but television was dominated by escapist fare like “Bewitched” and “Bonanza.” “All in the Family” was designed to explode the medium’s taboos, using an incendiary device named Archie Bunker. A Republican loading-dock worker living in Queens, Bunker railed from his easy chair against “coons” and “hebes,” “spics” and “fags.” He yelled at his wife and he screamed at his son-in-law, and even when he was quiet he was fuming about “the good old days.” He was also, as played by the remarkable Carroll O’Connor, very funny, a spray of malapropisms and sly illogic.

CBS arranged for extra operators to take complaints from offended viewers, but few came in—and by Season 2 “All in the Family” was TV’s biggest hit. It held the No. 1 spot for five years. At the show’s peak, sixty per cent of the viewing public were watching the series, more than fifty million viewers nationwide, every Saturday night. Lear became the original pugnacious showrunner, long before that term existed. He produced spinoff after spinoff (“cookies from my cookie cutter,” he described them to Playboy, in 1976), including “Maude” and “The Jeffersons,” which had their own mouthy curmudgeons. At the Emmys, Johnny Carson joked that Lear had optioned his own acceptance speech. A proud liberal, Lear had clear ideological aims for his creations: he wanted his shows to be funny, and he certainly wanted them to be hits, but he also wanted to purge prejudice by exposing it. By giving bigotry a human face, Lear believed, his show could help liberate American TV viewers. He hoped that audiences would embrace Archie but reject his beliefs.

Yet, as Saul Austerlitz explains in his smart new book, “Sitcom: A History in 24 Episodes from ‘I Love Lucy’ to ‘Community,’ ” Lear’s most successful character managed to defy his creator, with a “Frankenstein”-like audacity. “A funny thing happened on the way to TV immortality: audiences liked Archie,” Austerlitz writes. “Not in an ironic way, not in a so-racist-he’s-funny way; Archie was TV royalty because fans saw him as one of their own.”