Drops of rain collect in pools around potted plants outside the Marshall home in South Dos Palos, as a storm rolls into the small farming community about 100 miles southeast of San Jose. A wind chime hanging on the front porch provides background music to a family gathering inside in the living room.

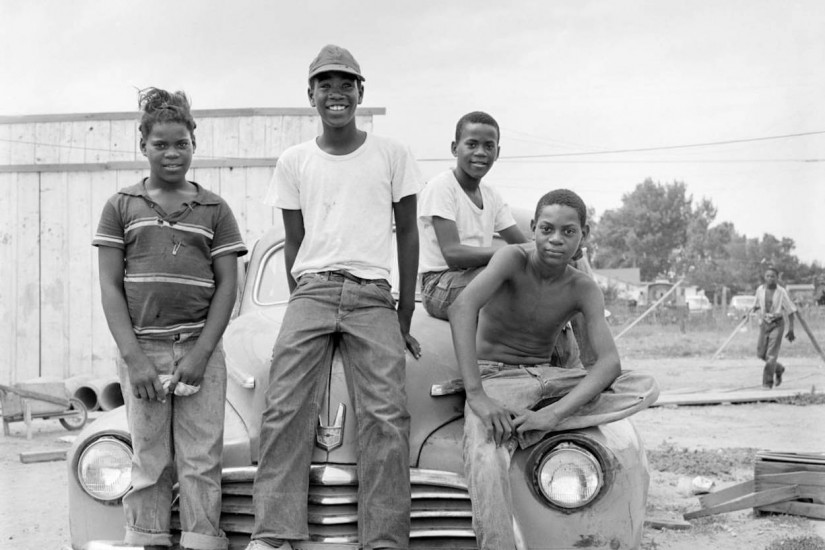

Joe, Lee, Zella, David and Marilyn Marshall are five of 13 siblings who grew up on this plot of land. Today, they're all in their 60s and 70s.

When the Marshall siblings’ father moved to the Central Valley from Mississippi in 1944 to work for the railroad, his goal was twofold: make enough money to provide for his wife and children, and put distance between his family and the racist laws of the South.

But the brothers say they found California had its own racism.

"The people in the South, they let you know right off the top, you not welcome, you not wanted,” Lee Marshall said. “And, 'Hey, don’t get out of place. You say mister to me.' And they demand that you say 'yes sir' and all this kind of stuff to 'em. It was just straight out, they didn’t hide it. That was better for me 'cause I know where you stand."

"These down here, there’s a hidden thing that they use on you," Lee Marshall said.

Lee's brother, Joe Marshall, said it was a more subtle form of racism the brothers faced growing up here.

“You know we could go anywhere and eat, it wasn’t a place where you had to go to the back door,” said Joe. “It was nothing like being in the South.”

“The difference between here and the South is just that — it’s hidden,” Joe said.

And that racism shaped how the Marshalls lived and worked. It also shaped the destiny of their town.

In the 1940s and 1950s, the Marshall brothers say South Dos Palos was thriving. The community was a hub of agricultural business and black-owned cafes, stores and service stations.

“Everything in South Dos Palos, except for a few places like behind us, was owned by black people,” Joe Marshall said.

Mexican and Central American workers make up the bulk of farm labor in California today, but throughout the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s, African-Americans and poor white families — many of them migrants who moved to the state during and after the Dust Bowl storms of the 1930s— also worked in the fields.