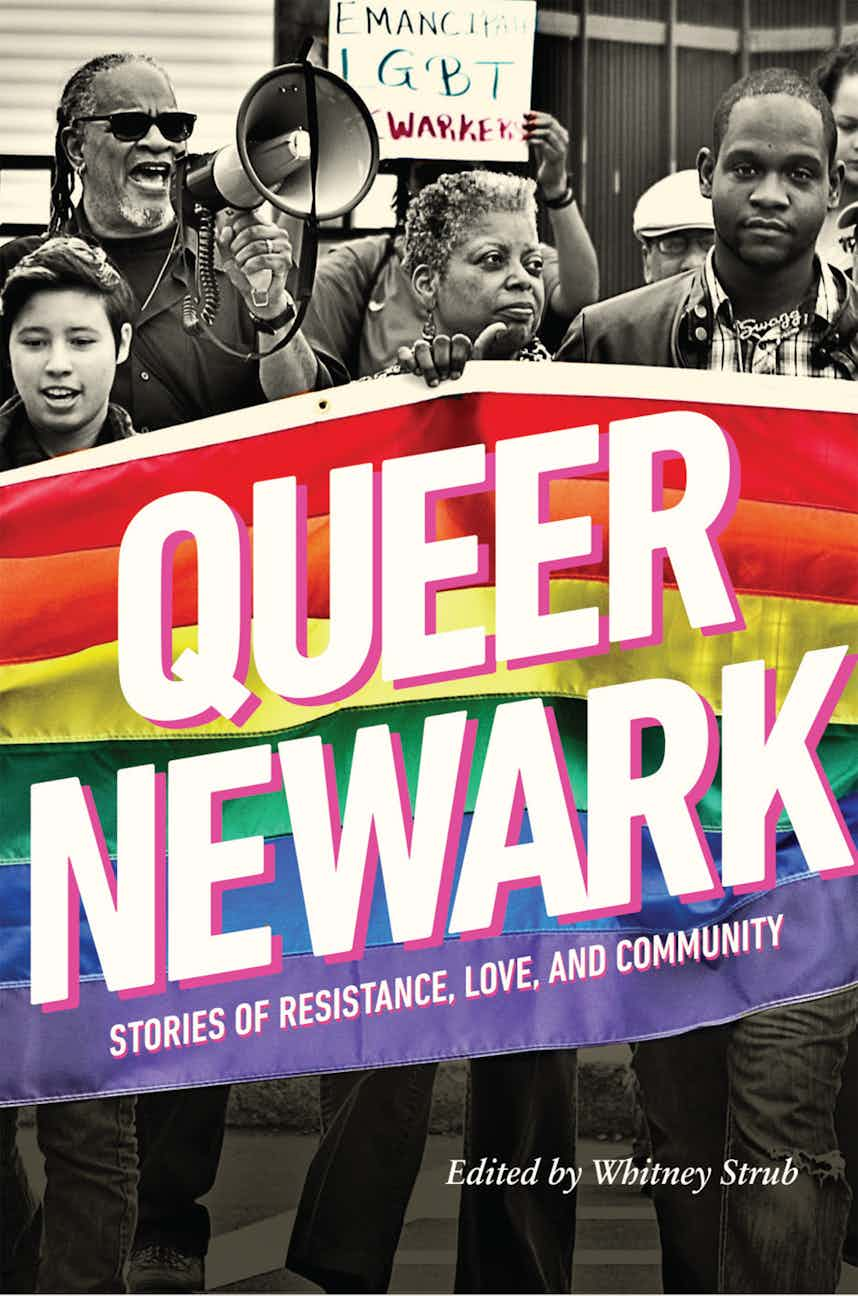

IN MEDIA and popular culture, Newark has long appeared as irredeemably unsexy, violent, destitute. “Queer Newark reclaims Newark,” Strub declares defiantly, “as a place of desire, love, eroticism, community, and resistance.” The book snuffs out the dominant view of the city, one ethnography and endnote at a time, centering squarely on the city’s poor and working-class Blacks and Latinos, especially Puerto Ricans and Brazilian immigrants. Queer Newark “highlights the intersectional ties between not only queerness and race and gender, but also queerness and class,” Strub writes, “for, like straightness in Newark, queerness here is markedly poor and working-class.”

The collection opens and closes with the heartbreaking story of Sakia Gunn, who was murdered on May 11, 2003, on the corner of Market and Broad Streets in the heart of downtown. Lovingly described as “young, gifted, Black, and queer,” Gunn “became an ancestor” for the crime of rejecting a man’s advances as she and her friends were returning from a night out in Greenwich Village. In the book’s epilogue, Zenkele Isoke, who studied Gunn in her dissertation, analyzes how a homegrown, Black lesbian–led movement in Newark organized actions and memorials, saving Gunn’s name from a silencing obscurity. Emblazoned on a mural along the McCarter Highway, “the longest mural on the East Coast,” is Tatyana Fazlalizadeh’s Sakia, Sakia, Sakia, Sakia, painted in Gunn’s honor. If not for this collective campaign of remembrance, Gunn’s story would have been neglected or forgotten, never receiving the attention given to, say, white, gay, and cisgender men such as Matthew Shepard or Tyler Clementi.1

Interspersed with these historical accounts are excerpts from the book’s namesake archive, the Queer Newark Oral History Project. Begun in 2011 at Rutgers-Newark, the project aims “to relocate both history and the power of narrating it away from the Ivory Tower and into the community as much as possible,” drawn from “listening sessions” with Newark queers of various ages and backgrounds. Valuable in itself, such an approach is also a practical necessity. Oral and extratextual methodologies are crucial in scholarship on multiply marginalized groups like queer and transgender people of color, historically excluded or erased from institutions that would produce and preserve documents like wills, contracts, letters, or diaries. (Even where such records have existed, they are often suppressed: love letters between gay GIs would be thrown in the trash; family members would deny or destroy evidence of the sexuality of gay male kin who died of AIDS in the 1980s.)