Wharton was a practical woman, as savvy about business affairs as social conventions, and she eventually overcame her fear of ghost stories enough to become a master of the form. Near the end of her life, in her mid-seventies, she spent time putting together a selection of her best ghost stories for publication. It was one of her final literary acts; she died in August, 1937, at her lavish home in the north of France. A New Yorker by birth, she had been an expat for two decades by then. She had grown increasingly preoccupied with the past, having lost many friends to war or illness, and her own health was failing. In “All Souls’,” one of Wharton’s last stories, a rich old woman wakes to a mysteriously empty house, surrounded by deep snow. She is injured—a fractured ankle—and cut off from the outside world, and she drags herself through the rooms looking for help. The silence is oppressive. (“It was not the idea of noises that frightened her, but that inexorable and hostile silence,” she wrote.) One of Wharton’s biographers, Hermione Lee, in her doorstopper on the author’s life, described “All Souls’ ” as “a story about the terror of death.”

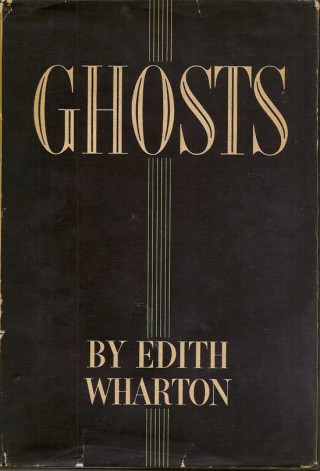

For a writer known mostly for incisive social novels about the old New York of her childhood, Wharton’s ghost stories make up a significant chunk of her œuvre. In addition to longer works, including “The House of Mirth” and “Ethan Frome,” she published some eighty-five short stories, many of them spectral. Wharton’s ghost tales have been anthologized alongside other American masters of unease—Edgar Allan Poe, whom she admired, and her good friend Henry James—but her 1937 collection, which was published shortly after her death, has long been out of print. This October, it will be revived by NYRB Classics, with the same preface it was initially published with, and the same title, “Ghosts.” Spanning the length of Wharton’s career—the earliest story, “The Lady’s Maid’s Bell,” is from 1902—the tales appear in their original, somewhat perplexing order. Wharton seems to not have arranged them chronologically or thematically, but according to her own mysterious preferences. “I liked the idea of, ‘This is exactly what she put out,’ ” Sara Kramer, the executive editor of NYRB Classics, told me.