A war on science raged across America in the early 19th century. Poe, as a writer, critic, and thinker, battled for both sides. A new biography—The Reason for the Darkness of the Night: Edgar Allan Poe and the Forging of American Science, by the historian John Tresch—situates its subject in a maelstrom of competing tides, as a new class of engineers and experimentalists splashed up against philosophers, theologians, and cranks. “Understanding his life and work,” Tresch maintains, “demands close attention to his multiform engagements with” scientific thought and discoveries.

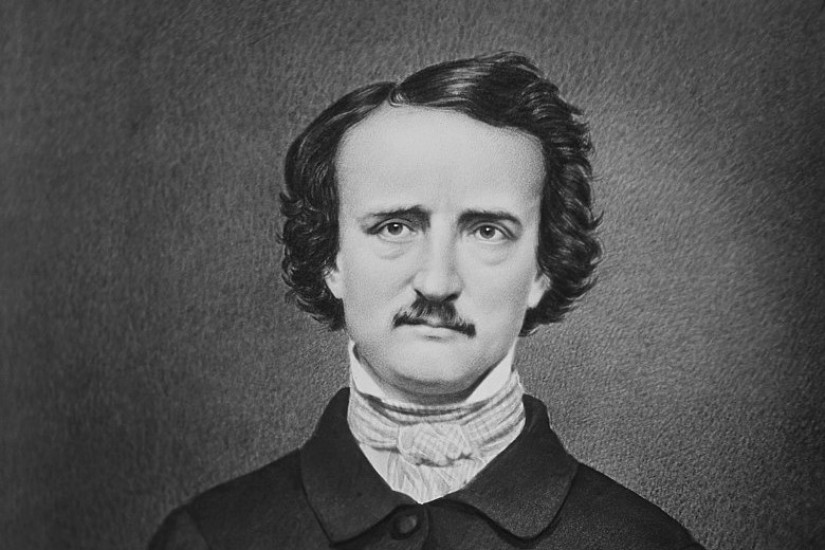

Poe certainly had a scientific cast of mind: In 1830, at the age of 21, he was admitted to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point—a scientific school, modeled on the École Polytechnique, in France, and meant to be a training ground for top-flight engineers. Poe showed promise, too. Before dropping out, he placed 17th in math out of 87 cadets. A few years later, he helped produce a textbook on conchology that sold more copies during his life than any other volume bearing his name. Among its selling points were several hundred color illustrations of seashells.

By 1840, Poe was working at a men’s magazine, where he launched a feature called “A Chapter on Science and Art,” consisting of the sorts of squibs on innovation later found in Popular Mechanics. (“A gentleman of Liverpool announces that he has invented a new engine,” one entry started.) With this column, Tresch suggests, “Poe made himself one of America’s first science reporters.” He also made himself one of America’s first popular skeptics—a puzzle master and a debunker, in the vein of Martin Gardner. Poe wrote a column on riddles and enigmas, and he made a gleeful habit of exposing pseudoscience quacks.

D. H. Lawrence once said that Poe engaged in “an almost chemical analysis of the soul and consciousness.” It’s true that his art was scientific, in a way. At times this was explicit, as in his science-fiction tales that took the form of medical case histories, or travelogues and news reports about ballooning. But as a critic, too, Poe searched for meaning in mechanics. He often railed against Romantic verse and the Boston clique of transcendentalists with their Yoda-like adherence to the sanctity of nature. In print, he called Ralph Waldo Emerson (one of this magazine’s co-founders) a “mystic for mysticism’s sake” and James Russell Lowell (this magazine’s first editor) “a fanatic for the sake of fanaticism.” Poe also provoked his readers with disquisitions on the technological basis for his literary work, laying out how he would take a poem “step by step, to its completion, with the precision and rigid consequence of a mathematical problem.”