There’s never been a more curious work in Edgar Allan Poe’s oeuvre than his 1848 epic, Eureka: A Prose Poem. A freewheeling attempt to describe the origins of the cosmos, filled with lofty abstractions and often turgid prose, it got a lukewarm reception at the time and has since largely been dismissed by both readers and critics. Too slapdash to be legitimate scientific inquiry, and too self-serious to be good writing, it seems, at best, an overeager misstep and best left forgotten. Indeed, given Poe’s propensity for hoaxes and passing off fiction as fact (including The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym), scholars have been unsure, as Susan Manning noted in 1989, about “the degree but also the quality of the seriousness” with which they should approach Eureka. Treating Eureka without irony, Manning continued, was “an appalling prospect.” It would mean scholars would “have to follow his arguments, test his analogies, weigh his conclusions—and all with a similarly ponderous solemnity.”

Poe, however, thought the poem more than serious—he saw it as nothing less than his greatest work. He told friends he believed Eureka would “revolutionize the world of Physical & Metaphysical Science. I say this calmly—but I say it.” Though he wasn’t even 40 years old when he wrote it, Poe nonetheless saw it as his crowning achievement; as he told his mother-in-law after its publication, “I do not wish to live. I could accomplish nothing more since I have written Eureka.”

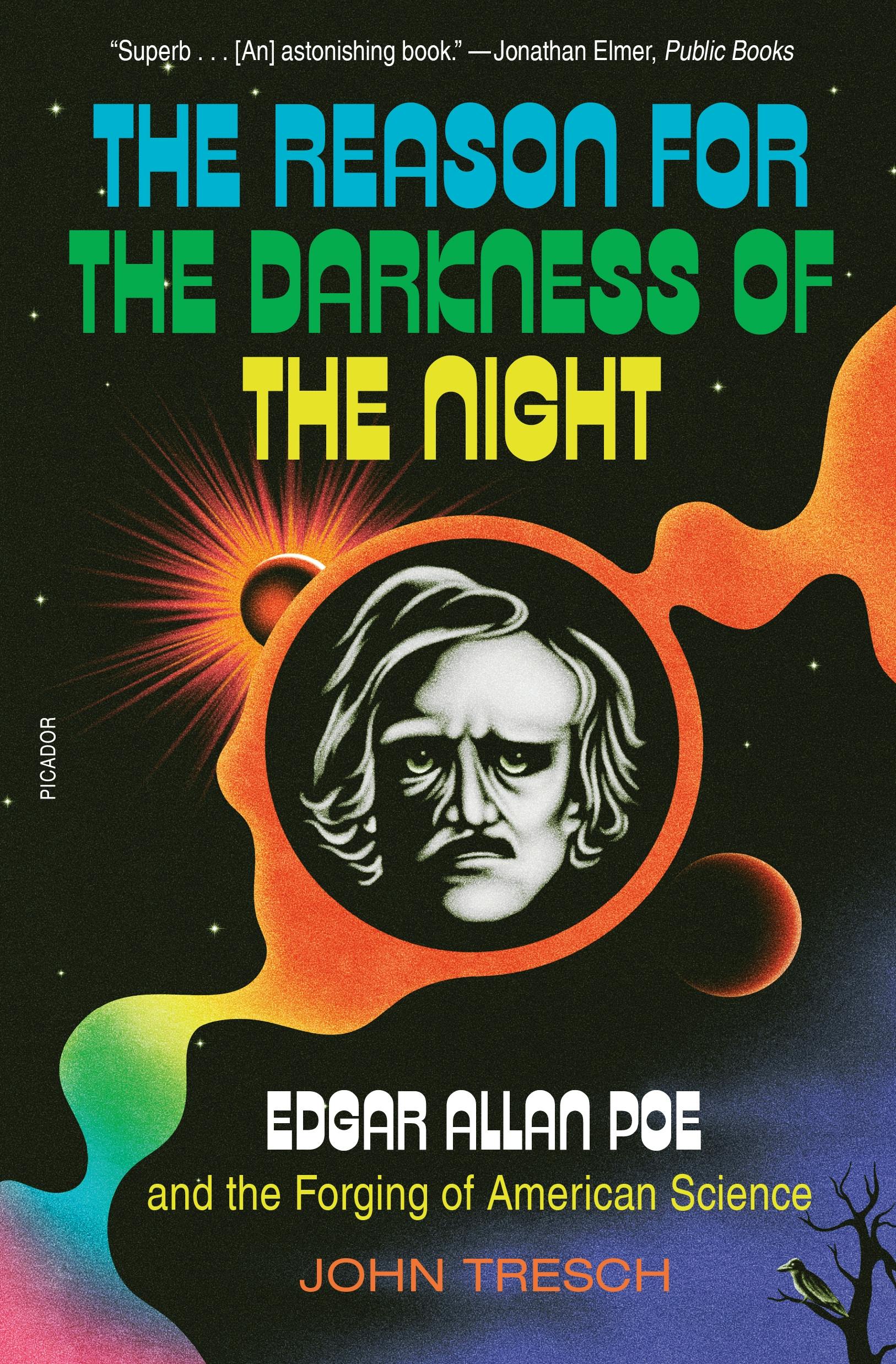

More known for ever-popular works like “The Raven” and “The Tell-Tale Heart,” Poe saw his real, unique contribution to American letters in a cosmological and philosophical treatise that is now rarely read or discussed. The fact that he saw it as the culmination of his entire life’s output suggests that we might have been missing something in Poe’s work this whole time. John Tresch’s new biography, The Reason for the Darkness of the Night: Edgar Allan Poe and the Forging of American Science, is the rare study that does not see Eureka as an aberration. Tresch suggests instead that the poem can offer a key to much of Poe’s more famous writing—lacking the svelte frisson of his great horror tales, perhaps, but offering an insight nonetheless into the obsessions that spawned them.