“The social organization which is most true of itself to the artist is the boy gang,” Allen Ginsberg once observed. It’s a sentiment that Frank Sinatra would have appreciated. The time of “Howl” and “On the Road” was also the time of “Frank Sinatra Sings for Only the Lonely” and the original “Ocean’s Eleven,” and although by many measures a taste for the product of North Beach is incompatible with a taste for the product of Las Vegas, the Beat Movement writers and the Rat Pack entertainers were shapers of a similar sensibility.

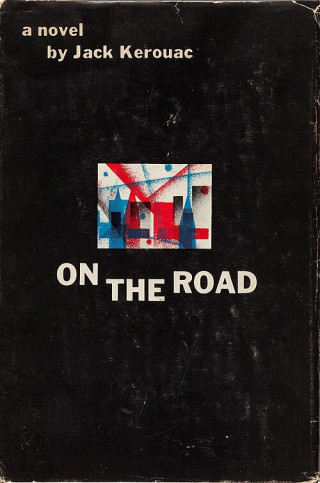

When “On the Road” came out, in September, 1957, it was praised in the New York Times as the novel of the Beat Generation, equivalent in stature and significance to “The Sun Also Rises,” the novel of the Lost Generation. The book was a best-seller, and it made Jack Kerouac, who had worked on it for ten years, a celebrity. It is sometimes said of Kerouac that fame killed him—that he was driven crazy by being continually addressed as the spokesman for a generation and by endless unwelcome requests to explain the meaning of the term “Beat.” Kerouac was certainly undone by something. After the success of “On the Road,” he continued to write at a manic pace, as he always had, but he became a suicidal alcoholic, and he died, of a hemorrhage caused by acute liver damage, in 1969, at the age of forty-seven. (He had by then written more than twenty-five books.) The notion of the Beat Generation was hardly thrust upon him, though.

“Beat” is old carny slang. According to Beat Movement legend (and it is a movement with a deep inventory of legend), Ginsberg and Kerouac picked it up from a character named Herbert Huncke, a gay street hustler and drug addict from Chicago who began hanging around Times Square in 1939 (and who introduced William Burroughs to heroin, an important cultural moment). The term has nothing to do with music; it names the condition of being beaten down, poor, exhausted, at the bottom of the world. (It’s used often in this sense in “On the Road.”) In 1948, Kerouac is supposed to have remarked, in a conversation with the writer John Clellon Holmes, “You know, this is really a beat generation” (followed by a spooky “only the Shadow knows” laugh), and Holmes thought enough of the phrase to use it as the working title of a novel, eventually published as “Go,” and to write an article for the Times Magazine, in 1952, called “This Is the Beat Generation,” in which he credited Kerouac with the term. (The article was solicited by the man who, five years later, wrote the Times’ review of “On the Road,” Gilbert Millstein.)