No matter the politics of the day, Jefferson tethered his gaze to earth, soil and sky. Revolutions roiled America and Europe for a half-century, but Jefferson held fast to noting weather’s daily whirl. He was curious to see where it carried the animals, plants and people that only “nature and nature’s God” might govern. His was a small and steady habit, vital for a politician who saw America’s future spelled out in farmers’ success. “Cultivators of the earth are the most valuable citizens,” Jefferson wrote. “They are the most vigorous, the most independent, the most virtuous, and they are tied to their country and wedded to its liberty and interests by the most lasting bands.”

Between July 1776 and June 1826, Jefferson recorded conditions in 19,000 observations across nearly 100 locations. All of this data is now available in a special digital edition of his climate and weather records, thanks to the Papers of Thomas Jefferson project and the Center for Digital Editing at the University of Virginia. The president left a meticulous interpretation of how the world, from Monticello to Paris, met with meteorology. Hunching over details, Jefferson took daily readings at sunrise and in the late afternoon. He tried to get a good fix on low and high temperatures. He logged barometric pressure, air moisture (hygrometer readings), wind direction and force, precipitation, and the ebb and flow of natural phenomena. He saved this data in ledger books, memorandum books, almanac sheets or loose folios.

Weather gossip filled his incoming mail with friends, like James Madison and Ezra Stiles, who sent diligent reports. “Adieu my dear papa,” daughter Martha Jefferson Randolphwrote in a July 2, 1792, missive. “The heat is incredible here. The thermometer has been at 96 in Richmond, and even at this place, we have not been able to sleep comfortably with every door and window open. I don’t recollect ever to have suffered as much from heat as we have done this summer.” Fierce weather could wilt fall crops, scorch voter turnout in winter, or sink spring ships bearing news and mail. Jefferson saw that better record-keeping was key. He harvested data and spun through scenarios, weighing agricultural needs against new innovations.

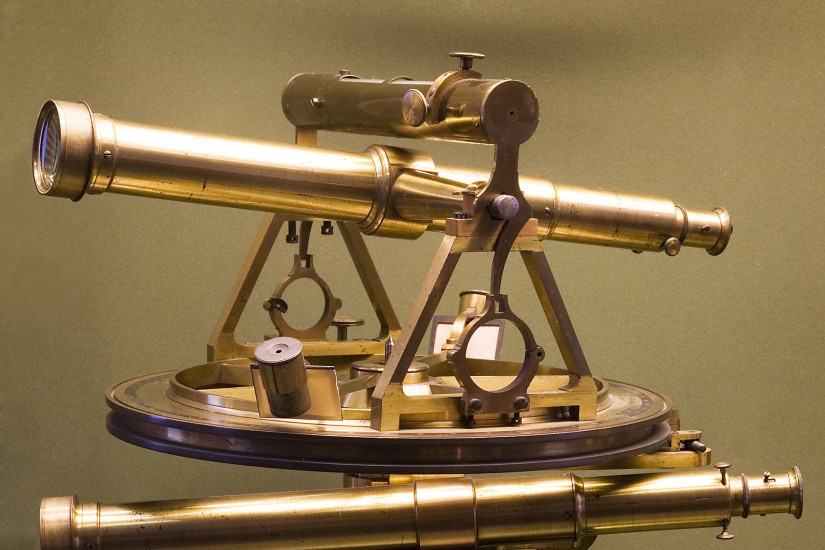

Where and when could American farmers grow the best strawberries, olives and grapes? Which bird calls signaled a change of season? Armed with a pencil and his reusable ivory notebook—wiped clean weekly as he transferred data, spreadsheet-style, to his papers—Jefferson struggled to make useful links between climate and geography. “For example, no one had yet worked out empirically what the differences might be in the weather of Philadelphia and Virginia, or between lower and higher elevations of land,” McClure says. “His motivation seems to have been to fill out parts of that big picture.” Jefferson clocked winds, listed temperatures, ranked rainfalls. He made sure his at-home weather lab was well stocked and ready for chance discovery.