The environmental justice movement—the fight of Black, brown, immigrant, indigenous, and poor communities to free themselves of unequal environmental burdens (dirty air, unclean water, toxic chemicals, etc.)—is often said to have begun in late 1978, when a group of Black homeowners in Houston hired the attorney Linda McKeever Bullard to halt the opening of a landfill just feet from their local public school. In 1982 Black residents of Warren County, North Carolina, launched a sit-in campaign to protest their exposure to toxic chemicals, generating headlines nationwide. Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, major studies conducted by the federal government, the United Church of Christ, and the sociologist Robert Bullard (the Houston attorney’s husband) documented the disproportionate location of dumps and landfills in Black neighborhoods—a phenomenon that came to be called “environmental racism.”

In 1991 the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit met in the nation’s capital, and within a few years various federal agencies had committed (at least on paper) to the movement’s goals. While scholars have noted the importance of earlier events—the 1968 sanitation workers’ strike in Memphis (at which Martin Luther King Jr. spoke just before his assassination) or the United Farm Workers’ campaigns to eliminate pesticides during the 1960s—the movement is nonetheless generally thought to have originated in the 1980s and 1990s and in the urban South.

In Toxic Debt: An Environmental Justice History of Detroit, Josiah Rector, who teaches at the University of Houston, instead looks northward to Detroit and its environs. As a graduate student at Wayne State University in Detroit a decade ago, he first came across records that charted the city’s rich and often overlooked history of environmental justice organizing. It was also in Detroit that Rector, a white newcomer in a city that is nearly 80 percent Black, witnessed one of the most naked displays of environmental injustice in recent memory.

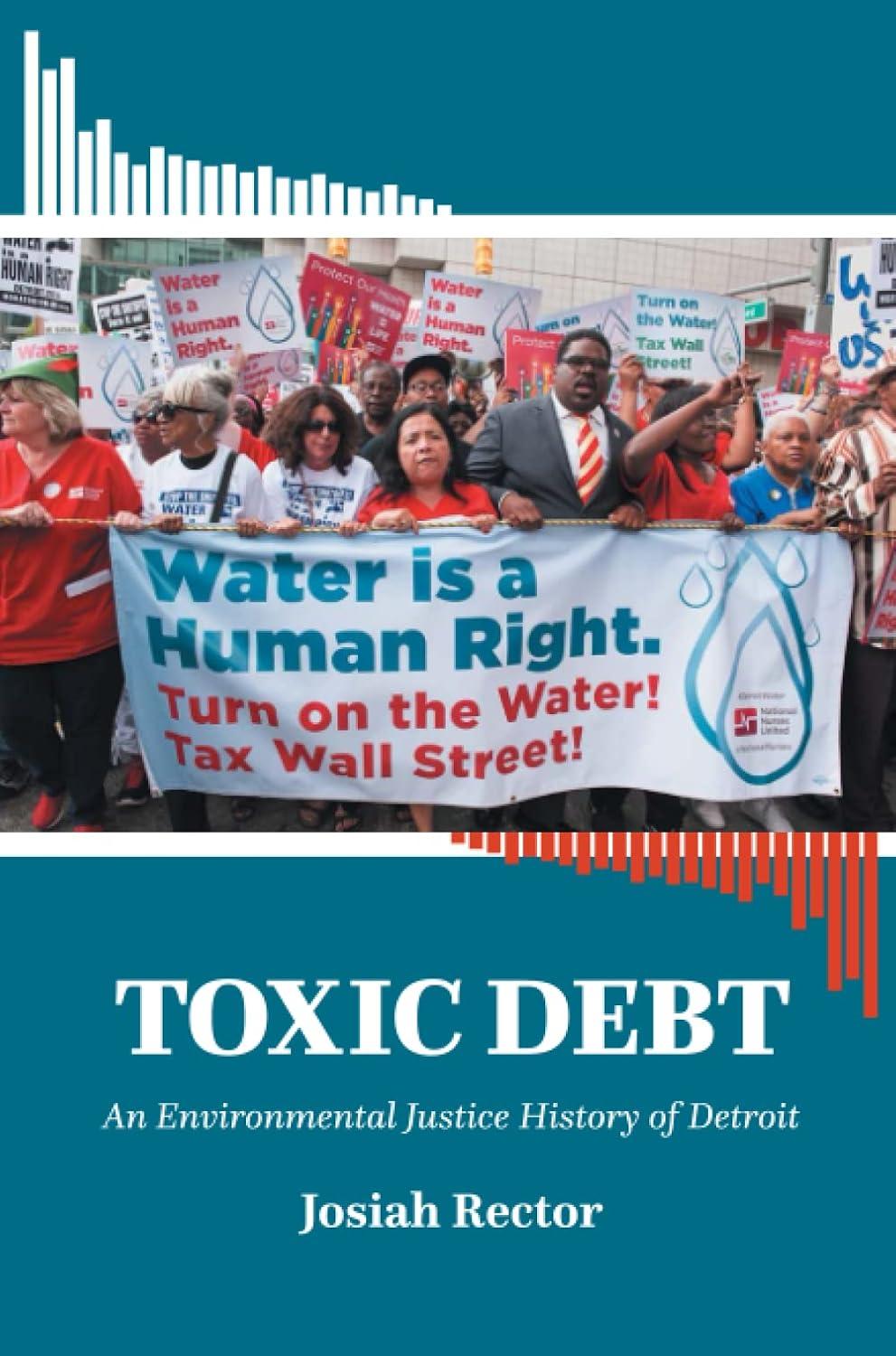

Beginning in 2014, the City of Detroit shut off the water of more than a quarter-million people. Starting at the same time, authorities in nearby Flint made a series of cost-cutting decisions that resulted in lead-laced water being pumped into thousands of homes. Astonishingly, Detroit’s water has been so foul for so long that its rate of childhood lead poisoning is twice as high as Flint’s—despite the fact that the city is surrounded by the largest freshwater system in the world. During Rector’s time there, moreover, Detroit recorded the highest rate of childhood asthma among the nation’s largest cities. A 2017 study estimates that air pollution causes 7 percent of all deaths in Detroit—more than twice the city’s rate of homicide.

After interviewing activists and immersing himself in the region’s archives, Rector concluded that the “existing literature on environmental justice did not give me the conceptual vocabulary I needed to make sense of what I was seeing in Detroit,” both past and present. A decade later, he has written a book that advances two major interventions. First, it pushes back the environmental justice movement’s genesis to midcentury union organizing. Second, and just as significantly, it firmly connects the effects of debt and austerity—that is to say, capitalism—to environmental racism.