A dozen or so soldiers, their limbs swollen in death, lie on the Gettysburg battlefield. Timothy O’Sullivan’s photograph cemented the grisly scene in America’s national consciousness. A Harvest of Death, he called it. A grim reaper had mowed down the flower of American manhood. At Gettysburg. Shiloh. Antietam. Vicksburg. The Civil War claimed over 750,000 soldiers. It remains by far the deadliest war in American history.

As stupefying as these numbers were, they were dwarfed by the far larger necropolis lying beneath America’s Civil War battlefields. In rocky tombs, formed millions of years before Gettysburg, rested the fossilized remains of a riotous wonder of life that had cavorted and gnashed its way through the continent’s primordial seas and landscapes. Brontosaurus and saber-toothed cats. Pterodactyls and the fearsome sea-serpent-like Elasmosaurus. Tiny belemnites, basically ice cream cones with tentacles, squirting their way through the shallows.

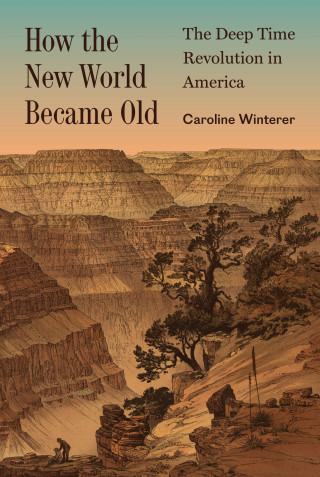

This lost world had been unearthed piecemeal in the decades between the Revolution and the Civil War. From New Jersey farms, Alabama cotton plantations, the Erie Canal, and the gullies of the Badlands emerged millions of fossils. The stony remnants of ancient creatures whispered to Americans that their continent might not be the New World after all. Perhaps the New World was just as old as the Old World. Or perhaps it was older still. Perhaps the four score and seven years stretching backward from Lincoln’s Gettysburg to the nation’s founding was a drop in the bucket of time. The American nation might be eighty-seven years old. But the American continent might stretch to the very basement of time.

This realization formed what I call the deep time revolution. Between the late eighteenth century and around 1900, Americans changed their minds about the age of the Earth. Simply: those who wrote and read the Declaration of Independence believed that the Earth was about 6,000 years old. This number was calculated by adding up the years and begats in the Bible. By 1900, many educated Americans believed instead that their planet had been formed billions of years before, and life upon it hundreds of millions years ago. Even by the era of the Civil War, the idea of deep time had spread to institutions and people across the United States–to colleges, natural history collections, private letters, scientific journals, even private diaries.

What did all these dead bodies mean? Not the Civil War dead, but the bodies of the countless fantastical creatures that had also perished from the Earth, entombed beneath cornfields and apple orchards millions of years before?