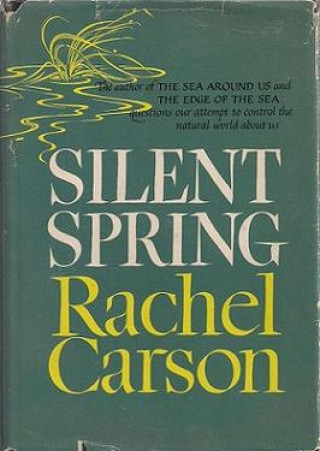

In the fall of 2020, a story broke on the front page of the Los Angeles Times. It featured a striking image of a barrel sitting on the floor of the ocean, emitting an eerie, phosphorescent glow. Over the past decade, the story explained, scientists had discovered thousands of barrels of acid sludge, a by-product of the manufacturing process for the notorious pesticide DDT, sunk off the coast of California. Enormous quantities of DDT waste had seeped out of the barrels and into the surrounding environment. It remained unclear, however, how much DDT was down there or how exactly—and even whether—any remediation efforts might be undertaken. “At this point,” writes the historian of science Elena Conis, “only one thing is clear: seventy-five years after scientists first warned of its hazards, sixty years after Rachel Carson wrote Silent Spring, and fifty years after it was banned, DDT is still here.”

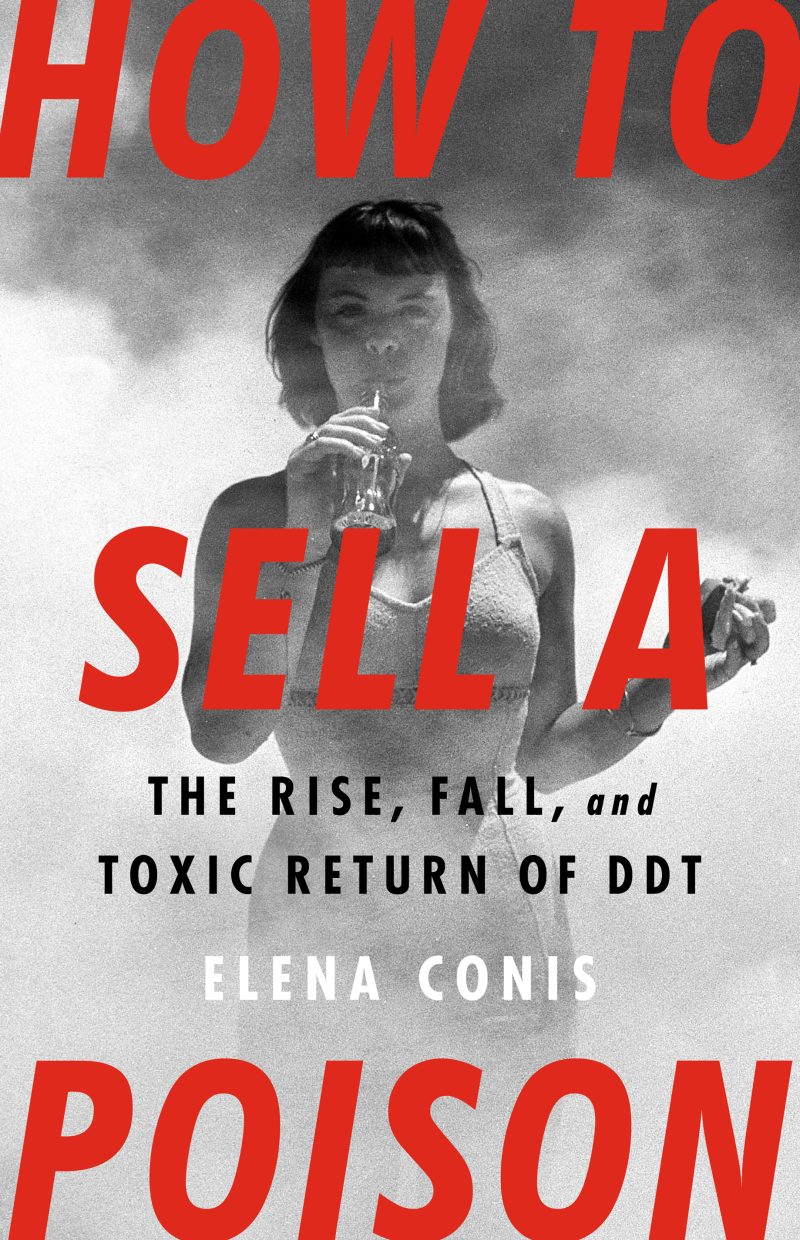

Indeed, as Conis details in her monumental—and monumentally disturbing—new book, How to Sell a Poison: The Rise, Fall, and Toxic Return of DDT, DDT remains in our soil, our water, the animals that surround us, and even within our very bodies. Yet the story of this infamous pesticide has long been incomplete. If you ask Americans to state what they know about DDT, most would probably describe the pesticide’s ubiquity before the ascendant environmental movement—led by Rachel Carson—forced the government to eliminate it. This story, while not exactly wrong, overlooks much of the complexity (and complicity) in DDT’s biography, including the numerous recent calls to bring the pesticide back into use again.

A former features writer and health columnist for the Los Angeles Times, Conis is probably best known for her book Vaccine Nation: America’s Changing Relationship With Immunization, which probed the histories of vaccine policy and vaccine hesitancy years before the advent of the Covid-19 pandemic. She now teaches journalism, public health, and history at the University of California, Berkeley, making her perhaps uniquely qualified to recount this complicated story.

For years, Conis writes, she taught her students the familiar three-act story of DDT: First, it was a hero, sprayed all across the United States with abandon; then, it was a pariah, denounced by Rachel Carson and quickly banned by the federal government; but then, it experienced an unlikely popular resurgence, as many demanded that the ban be lifted, acknowledging DDT’s toxicity yet claiming it was needed to fight malaria. “But the third act always nagged at me,” Conis writes. “Why was the late 1990s the moment when Americans started calling for DDT’s return?”

After years of research and archival digging, Conis arrived at what she calls an “unexpected answer”: the tobacco industry. For truly, was there ever any group better qualified to sell a poison?