Many know the general contours of the history of how Cornell and other land-grant universities were established under the federal Morrill Act of 1862. Such institutions – one per state – were established

to teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts … in order to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes in the several pursuits and professions in life. (7 U.S.C. § 304)

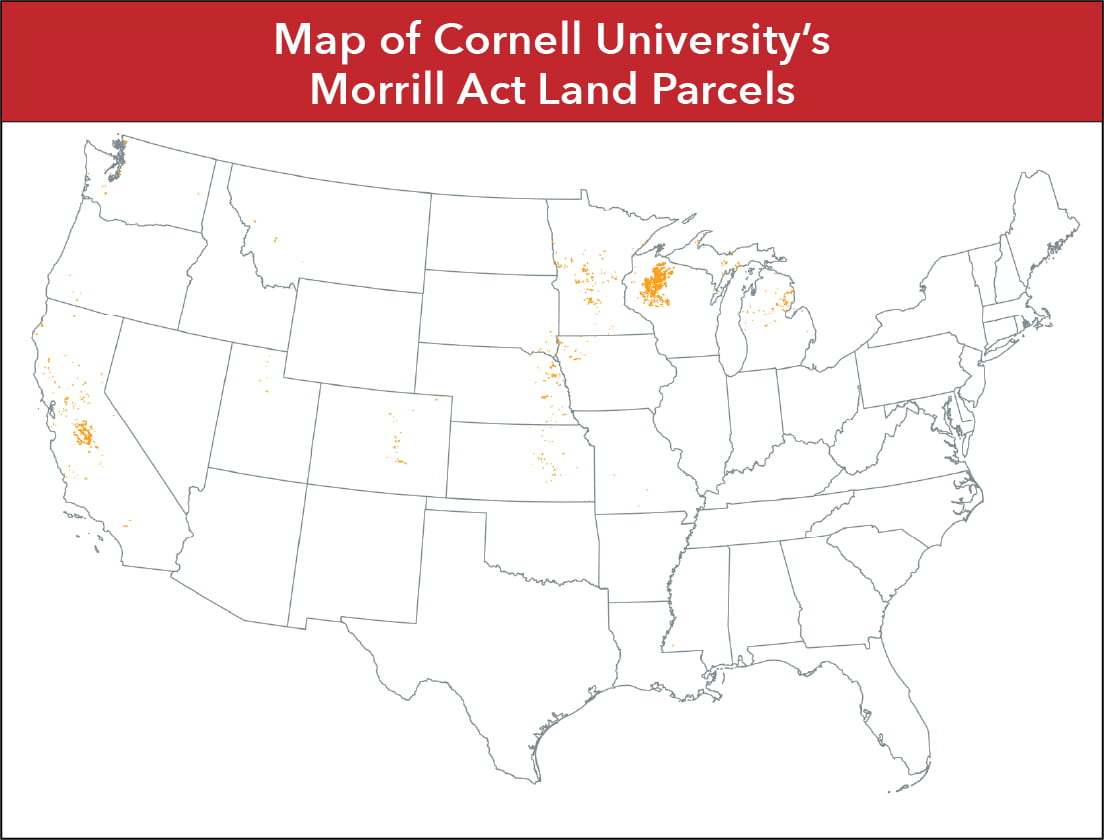

To fund this endeavor, the U.S. government provided grants of federally-held public lands that could be managed as speculative real estate by the institutions. Each state received 30,000 acres of land for each member of congress the state held following the 1860 census. Those institutions in states that had federal land within their borders received lands there, but many states (like New York) did not have sufficient federal lands and were awarded “scrip” (vouchers) to purchase public land elsewhere.

Cornell’s founder Ezra Cornell has long been recognized as a particularly savvy manipulator of scrip. The most famous instance of this was his acquisition of timber-rich former Indigenous lands in Wisconsin, which actually provided three separate types of revenue: they initially were logged and the timber products sold, then the land itself was sold, and finally, Cornell University has retained (and continues to profit from) mineral rights to some of that land to this day. This process is detailed in Cornell historian Paul Wallace Gates’ 1943 book The Wisconsin Pine Lands of Cornell University.

This story, unfortunately, goes much deeper than a celebration of Ezra Cornell’s business skills. A March 30, 2020 article published in High Country News by Robert Lee, lecturer in American History at the University of Cambridge and Tristan Ahtone, editor-in-chief of the Texas Observer, connects the awarding of federal “public” lands through the Morrill Act to the dispossession of Indigenous Nations from their traditional territories. The authors, alongside a team of other researchers, painstakingly reconstructed the details about the lands awarded to the various Land-Grant schools, whose homelands they were, and how much money the universities generated from the process. This landmark study provides a window into the Indigenous side of the Land-Grant process, something that has been obscured and ignored in over 150 years of celebratory narratives that focus on the positive outcomes of the Morrill Act.

The federal government acquired Morrill Act lands through treaties (some ratified, but others unratified by the United States Senate), executive orders, and in some cases without any sort of treaty or agreement whatsoever. In all instances, negotiations were backed by the force of the U.S. military and Indigenous Nations often had little or no bargaining power. Frequently violence, much of it genocidal in intent and impact, had taken place to expel Indigenous peoples shortly before U.S. universities obtained the land.