On September 20, 1945, the infamous Nazi scientist Wernher von Braun arrived at Fort Strong, a U.S. military site on Long Island in Boston Harbor. In a period when many of von Braun’s Nazi colleagues were preparing to be tried in the Nuremberg war crimes trials that would commence exactly two months later, von Braun and other Nazi scientists were instead being brought to the United States to serve as prized members (and often leaders) of teams researching the space program, weapons technology, and other initiatives. Known as Operation Paperclip, this secret endeavor, led by the federal government’s newly created Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency (JIOA), would eventually bring more than 1600 German scientists — many of them former Nazis — to America between 1945 and 1959.

The Soviet Union was similarly pursuing Nazi scientists for its own weapons and space programs, and so Operation Paperclip can be framed as part of the incipient Cold War, a reflection of how quickly and thoroughly the two nations pivoted from their tenuous World War II alliance to this new, multi-decade conflict. Yet at the same time, the relationship between the U.S. government and these Nazi scientists cannot be separated from the longstanding, deeply rooted presence of Nazis and antisemitism in America. From prominent figures and voices to mass movements and rallies, the two decades leading up to World War II featured numerous connections between Americans and Nazi Germany, links that reveal that Nazism was never simply a foreign or enemy force.

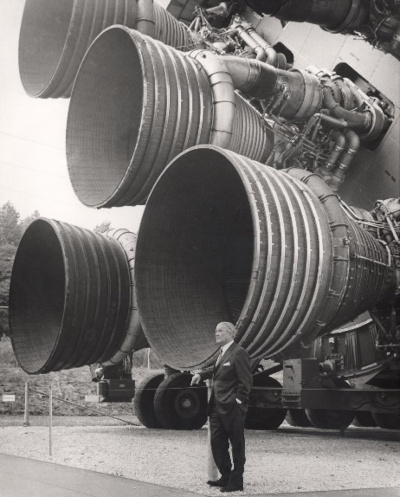

Wernher von Braun in front of five F-1 engines of the Saturn V Dynamic Test Vehicle (NASA)

One of those Americans with close ties to Nazi Germany was also one of the most successful and famous Americans of the early 20th century: Henry Ford. The automobile inventor and entrepreneur wasn’t just a strident anti-Semite—he was apparently an influence on the rise of German Nazism and even Adolf Hitler himself. Between 1920 and 1927, Ford and his aide Ernest G. Liebold published The Dearborn Independent, a newspaper that they used principally to expound anti-Semitic views and conspiracy theories; many of Ford’s writings in that paper were published in Germany as a four-volume collection entitled The International Jew, the World’s Foremost Problem (1920-1922). Heinrich Himmler wrote in 1924 that Ford was “one of our most valuable, important, and witty fighters,” and Hitler went further: in Mein Kampf (1925) he called Ford “a single great man” who “maintains full independence” from America’s Jewish “masters”; and in a 1931 Detroit News interview, Hitler called Ford an “inspiration.” In 1938, Ford received the Grand Cross of the German Eagle, one of Nazi Germany’s highest civilian honors.