Americans are at an impasse in their understanding of racism today. The activist slogan “Black Lives Matter” is met by the rejoinder “All Lives Matter” or “Blue Lives Matter.” Colin Kaepernick’s NFL protest about racial injustice is perceived only as an anti-American blast. President Trump tells reporters he is “the least racist person” they will ever interview. In each of these cases, conservatives feel deeply that they are not the bigots they are made out to be, declaring wide-eyed innocence in the face of any charge of racial animus.

This claim to racial innocence is not a new feature of the conservative movement, but rather one woven into the development of modern conservatism, part of an effort on the right to cleanse itself of its support for segregation and other racist policies, while heaping the blame for any racist outcomes in American society on their opponents on the left.

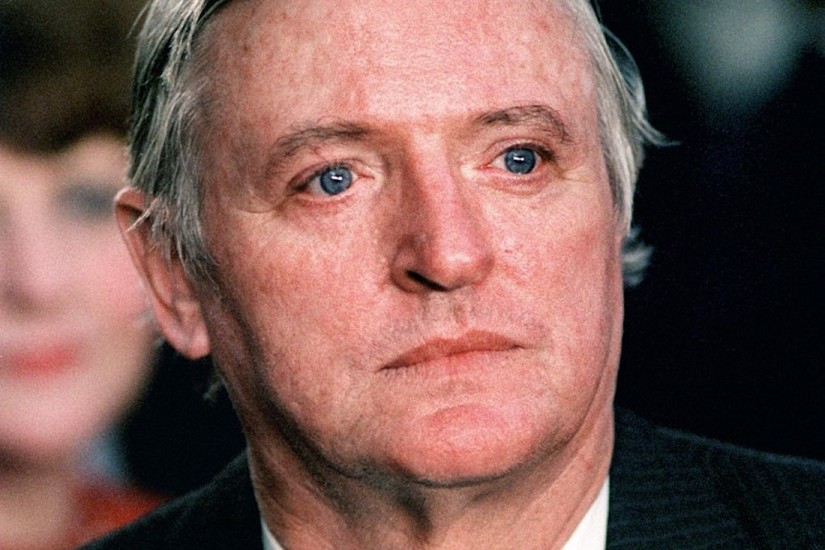

That process of racial purgation was captured in the pages of conservatism’s foremost intellectual outlet: National Review. In April 1965, William F. Buckley Jr., who founded National Review as a journal of “respectable conservatism,” spoke to a police breakfast in New York. Buckley reportedly praised the Alabama police for their restraint at Selma. The episode sparked fierce press condemnation.

Furious, Buckley held a news conference where he played a recording of the speech. The tape undermined reports that the police had cheered Buckley’s remarks about police violence, but the talk did defend the Alabama police, despite reservations about excessive force, and placed blame on civil rights activists for the confrontation.

It was really the charge of bigotry that incited Buckley. He hadn’t breathed “a word of prejudice against any people” he said in a statement. And he wanted to sue.

“If the Liberals succeed in anathematizing me as a seller of hate,” Buckley told the directors of his magazine, then “so is National Review.”

“If we show that we don’t care that people call us hate-peddlers, then, in a way we care less about hate-peddling,” he said.

As far as Buckley was concerned, National Review and respectable conservatism were at the fulcrum of genuine racial enlightenment: “non-racist” yet not ensnared in “dogmatic racial egalitarianism.”

The reality, however, was much more complex.