Forum Introduction

By Magdalene Zier, Lauren MacIvor Thompson, Cathleen Cahill, and Kimberly A. Hamlin

Anthony Comstock arrived in Washington, D.C., in January 1873 with a collection of pornography and big plans for what to do with it. Bearing a veritable grab bag of explicit images, books, pamphlets, contraceptives, and sex toys that he had ordered expressly for the purposes of shock, he set up displays, first in the private homes of legislators and then in the office of the vice president inside the congressional building.[1] As congressmen trooped by to gawk, Comstock spoke to them about the “nefarious business” of obscenity.[2] In just a few weeks, Congress would pass a sweeping law bearing his name, one that criminalized mailing anything to do with sex. “An Act of the Suppression of Trade in, and Circulation of, Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use” included not just pornography and sexual material, but also personal correspondence, educational pamphlets, contraceptives, and items related to abortion.[3] To enforce this sweeping new law, Comstock was appointed Special Agent of the Post Office and endowed with the power to search the mail, seize obscene items, and make arrests. He would soon proudly declare of his accomplishments: “I have endeavored to raise a legal barrier between the youth and this hydra-headed monster of Obscenity.”[4] He was not yet thirty years old.[5]

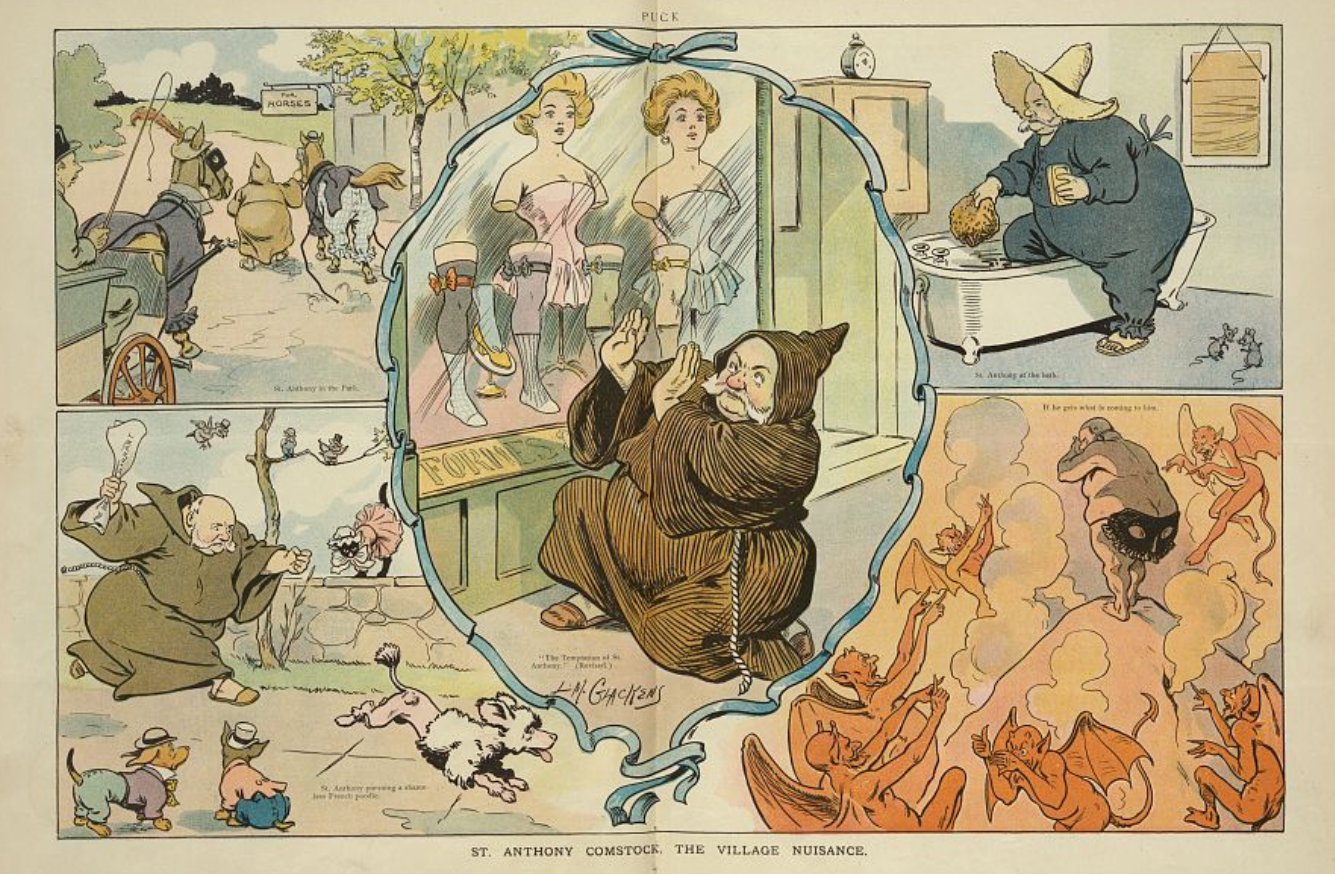

This blog series aims to provide vital historical context for those seeking to understand the modern revival of Anthony Comstock and his namesake law. The Comstock Act has never been repealed and remains part of Sections 1461 and 1462 in the United States Code, although many Americans have little to no idea about the details of this law, if they have even heard of it. Anthony Comstock himself seems like an odd joke today: a repressed, puritanical, anti-sex reformer and a relic of a bygone past (Figure 1). And yet, because the act has been revived as a strategy for limiting access to reproductive healthcare, Comstock is no joke. Some see the statute as a pathway to banning abortion and other reproductive care, which would effectively jettison any need for new Supreme Court abortion rulings or congressional legislation.[6] As scholars of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, we are uniquely situated to intervene in this dialogue and ensure that contemporary conversations are based on accurate information. We present this series not as an exhaustive account of the Comstock Act and its architect, but as an opportunity to highlight the context in which this law, which holds so much potential relevance for our present, was created, enacted, enforced, and challenged. We also hope that these blog posts will stimulate further scholarly and public conversations around this long history of regulating reproductive rights and how it became entangled with other social anxieties.