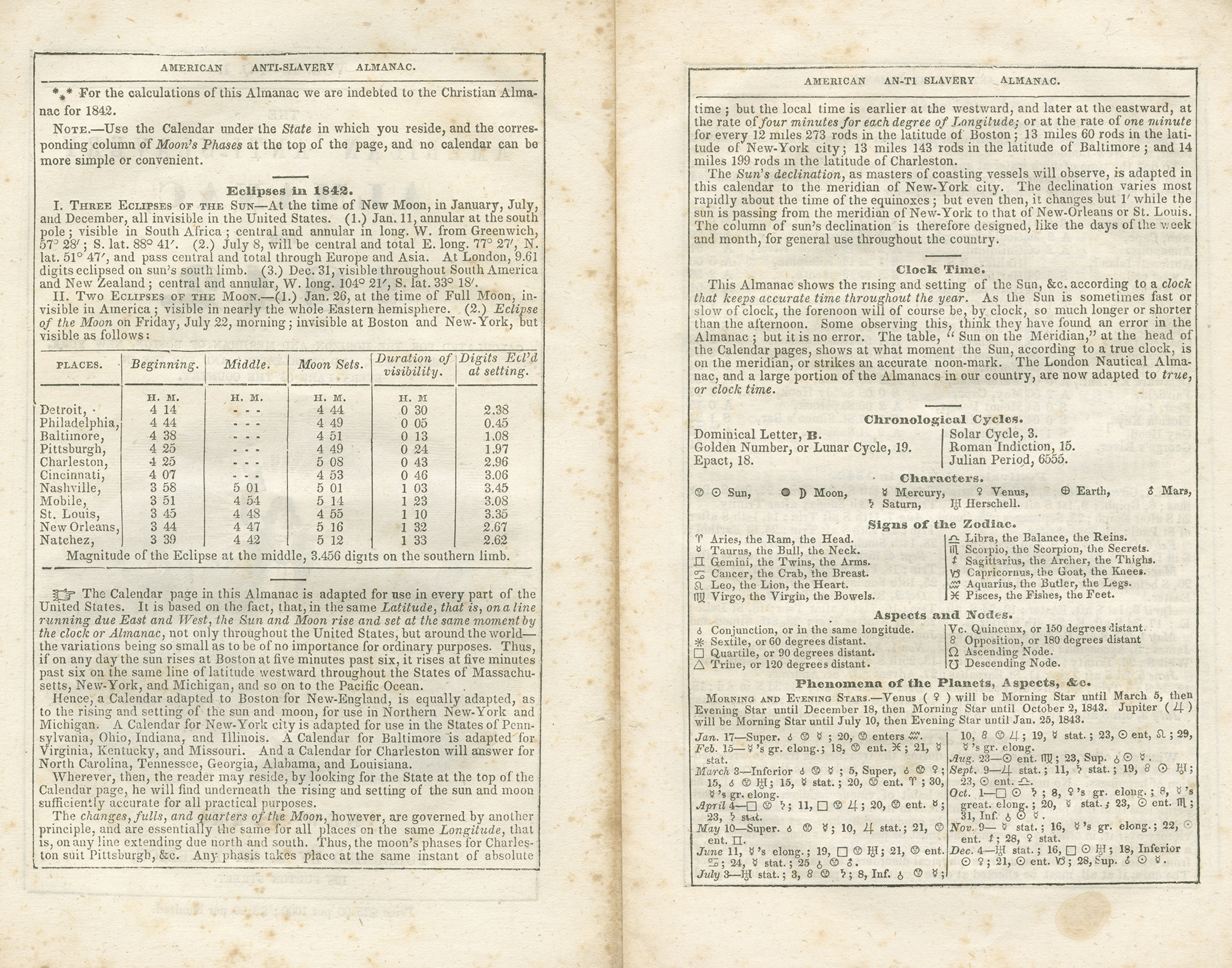

From The American Anti-Slavery Almanac for 1842. [Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture]

From its outset, the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS) worked to establish the facts of slavery. Antislavery lecturers were instructed to make themselves “familiar with FACTS, for they chiefly influence reflecting minds” and to “make no random statements, prove all things.” Periodicals regularly offered facts or statistics about slavery: the headlines of Human Rights declared facts! facts!! facts!!! and still more facts while the Quarterly Anti-Slavery Magazine published statistics of the U.S. slave population.

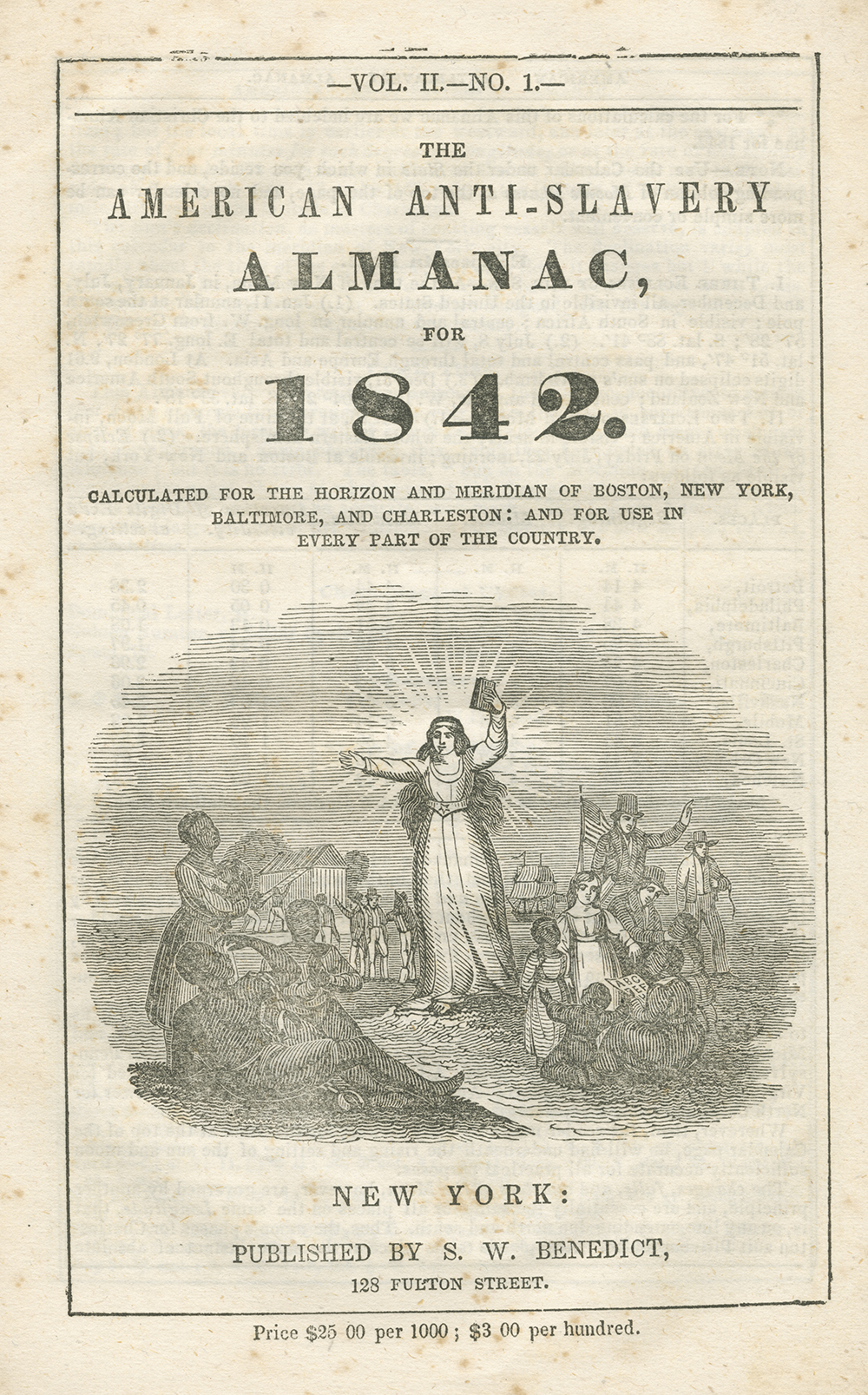

By ceaselessly creating facts and linking them together within a reinforcing print system, the AASS forged a factual foundation upon which to build its arguments. Throughout the 1830s, the AASS was an information-gathering, knowledge-producing enterprise. Its most prominent genre—the documentary compendium—was the principal print form through which it compiled, constructed, and dispersed facts about slavery. Its most popular factual compendium in the 1830s was the antislavery almanac. Driven by data, the antislavery almanac deployed the genre’s modes of information analysis to produce antislavery knowledge in a legible and familiar form. Framing its facts through the genre’s customary conventions, it trained its audience to calculate slavery’s immorality. It was also a key node in the AASS’ consolidated print system and the primary pamphlet in many of its distributional plans. Crucial to the formulation of the society’s factual argument, it was essential to its institutional credibility and organizational growth.

Through the almanac, the AASS established its knowledge system as sound and its movement as legitimate.

As historian Patricia Cline Cohen argues, a cultural shift toward numeracy occurred in the 1820s and 1830s. Arising in conjunction with the market revolution and the emergence of mass society, this shift was marked by the explosion of numbers, the popularity of statistics, “a mania for quantification,” and the invention of what historian and literary critic Mary Poovey terms “the modern fact.” Numeracy was a crucial tool of U.S. nation building in the nineteenth century. The state solidified its power through what Oz Frankel calls “print statism”—the unprecedented production, accumulation, and diffusion of facts in and through official reports and policy documents. Through the authority of statistics and the uniformity of print, the federal government sought to manage a rapidly expanding nation and represent its own identity as commanding. Reform movements similarly turned to numeracy to quantify and enumerate social ills—and thereby make them visible and comprehensible.

In the 1830s the AASS turned to the almanac—the informational genre of its day—to authenticate its argument. A miscellany of diverse information, statistical tables, charts, and computations, the nineteenth-century almanac was constituted as a collection of facts. Associated with prediction and superstition in the seventeenth century, by the late eighteenth century almanacs had become more rational, serving as vehicles for Enlightenment thought. Their statistical role—collecting, organizing, and analyzing data—expanded rapidly in the nineteenth century as the genre responded to the market economy and an increased demand for useful knowledge.

Cover of The American Anti-Slavery Almanac for 1842. Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.