The two films were Behind the Great Wall, made with the Aromarama system, conceived and developed by public relations executive Charles Weiss; and Scent of Mystery, which used the Smell-O-Vision process promoted by Mike Todd Jr., son of the legendary theatrical impresario and producer of the same name. By the late 1950s, television was in ascendency, and the movies sought to innovate—with 3-D, wraparound 360-degree screens, and the “smellies”—in order to see off this existential threat. Weiss showcased his technology, which used aerosol canisters to inject fragrances into the cinema’s general air supply system, with a travelogue, a sweeping panorama of China featuring Buddhist temples and Mongol warriors that had already won prizes at the Venice Film Festival and the Brussels World’s Fair. It was given a smell track that featured the aromas of floral processions, fireworks, and construction sites, the spicy scents of Hong Kong’s street markets, and the burned resin odors of a tiger hunt.

The documentary was first shown in December 1959 at the DeMille Theater in New York, which was converted for the task at the cost of $7,500. A triggering device was connected to the projector and electronic precipitators acted as “deodorizers” to filter the air between smells. However, the New York Post wrote: “The great green outdoors upon one occasion came through as celery tonic.” Bosley Crowther in the New York Times further elaborated on the film’s flaws: “In between the suffusions of odors, the air in the theatre is cleared by a purifying treatment that itself leaves a sticky sweet smell, which tends to become upsetting before the film has run its full two hours. When this viewer emerged from the theatre, he happily filled his lungs with that lovely fume-laden New York ozone. It never has smelled so good.”

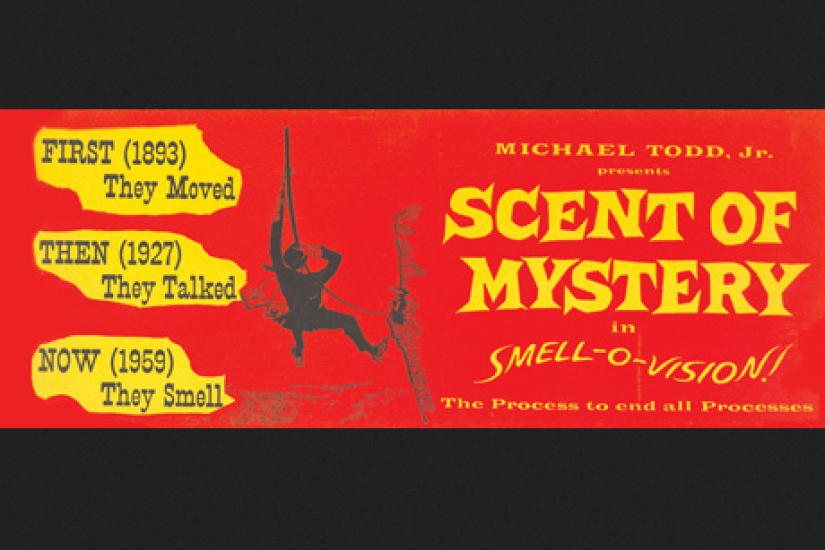

In contrast, the more sophisticated Smell-O-Vision process, used for the comedy-mystery film Scent of Mystery, cost $30,000 to install and allowed smells to dissipate naturally into the air. The odors were manufactured by Professor Hans Laube, a former advertising executive from Switzerland turned “world-renowned osmologist.” According to his daughter, Carmen, he thought that everything had a smell, including emotions; he once asked her to throw open the window because the room stank of ego. Laube was the inventor of a method for clearing the air in large auditoriums, and a logical extension was that he could also pipe smells in. He had shown what he called a Scentovision film, featuring several odors, as early as 1939 in the Swiss pavilion at the New York World’s Fair, which was also host to Michael Todd’s Hall of Music, featuring live performances by Gypsy Rose Lee. The Todds, known for their theatrical stunts and pioneering new processes, had been contemplating making a smell film for almost a decade, but it is unclear whether they first got wind of a feasible technology there. In 1943, the New York Times reported that Scentovision “produced odors as quickly and easily as the soundtrack of a film produces sound.”