“I’m completely in praise of what Tim Berners-Lee did,” Kahle told me, “but he kept it very, very simple.” The first Web page in the United States was created at slac, Stanford’s linear-accelerator center, at the end of 1991. Berners-Lee’s protocol—which is not only usable but also elegant—spread fast, initially across universities and then into the public. “Emphasized text like this is a hypertext link,” a 1994 version of slac’s Web page explained. In 1991, a ban on commercial traffic on the Internet was lifted. Then came Web browsers and e-commerce: both Netscape and Amazon were founded in 1994. The Internet as most people now know it—Web-based and commercial—began in the mid-nineties. Just as soon as it began, it started disappearing.

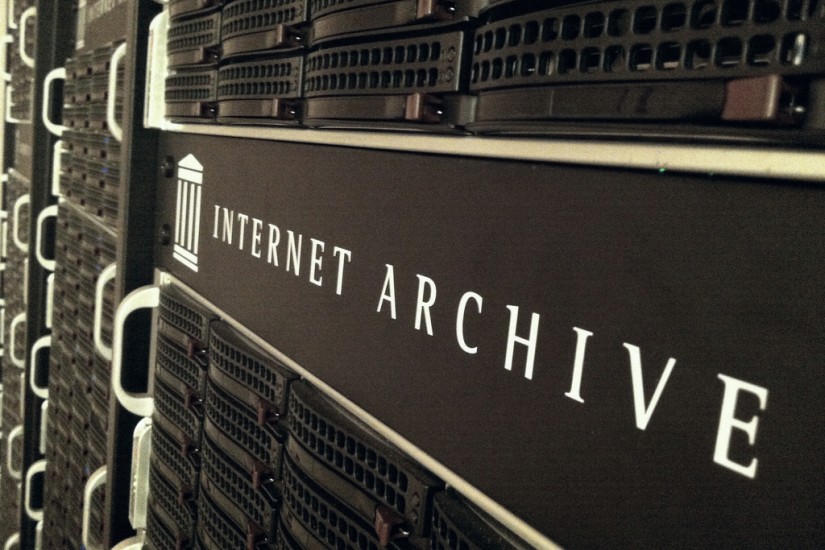

And the Internet Archive began collecting it. The Wayback Machine is a Web archive, a collection of old Web pages; it is, in fact, the Web archive. There are others, but the Wayback Machine is so much bigger than all of them that it’s very nearly true that if it’s not in the Wayback Machine it doesn’t exist. The Wayback Machine is a robot. It crawls across the Internet, in the manner of Eric Carle’s very hungry caterpillar, attempting to make a copy of every Web page it can find every two months, though that rate varies. (It first crawled over this magazine’s home page, newyorker.com, in November, 1998, and since then has crawled the site nearly seven thousand times, lately at a rate of about six times a day.) The Internet Archive is also stocked with Web pages that are chosen by librarians, specialists like Anatol Shmelev, collecting in subject areas, through a service called Archive It, at archive-it.org, which also allows individuals and institutions to build their own archives. (A copy of everything they save goes into the Wayback Machine, too.) And anyone who wants to can preserve a Web page, at any time, by going to archive.org/web, typing in a URL, and clicking “Save Page Now.” (That’s how most of the twelve screenshots of Strelkov’s VKontakte page entered the Wayback Machine on the day the Malaysia Airlines flight was downed: seven captures that day were made by a robot; the rest were made by humans.)