To understand representations of disaster in the 1830s and 1840s, we must first examine the semantics of the term within the historical context. A survey of antebellum news sources indicates that writers applied the word disaster liberally to a range of events—everything from a single death to a mass loss of life or property. Disasters usually entailed an unforeseen disruption of everyday life and could be caused by both natural and technological forces: fires, violent storms, floods, earthquakes, industrial mishaps, and ship- and train wrecks. But the word was also used more figuratively and appeared frequently in discussions of economic or political policy.3 The indiscriminate use of the term speaks to the meaning and social function of disasters in the era: the origin of the word disaster—from the Italian, meaning “ill-starred”—is retained in antebellum associations, consistently linked as it is in the Victorian mind with fate or Providence.4 Individual fates, the fate of the economy, the fate of one’s business, and the fate of the nation or of humanity were all abiding preoccupations in the pre–Civil War era. In this period, any sudden occurrence perceived to divert or truncate the course of individual, community, or state qualified as a disaster. Any unexpected incident—great or small—seemed to warrant a moment of reckoning with destiny and the many issues that might attend it.

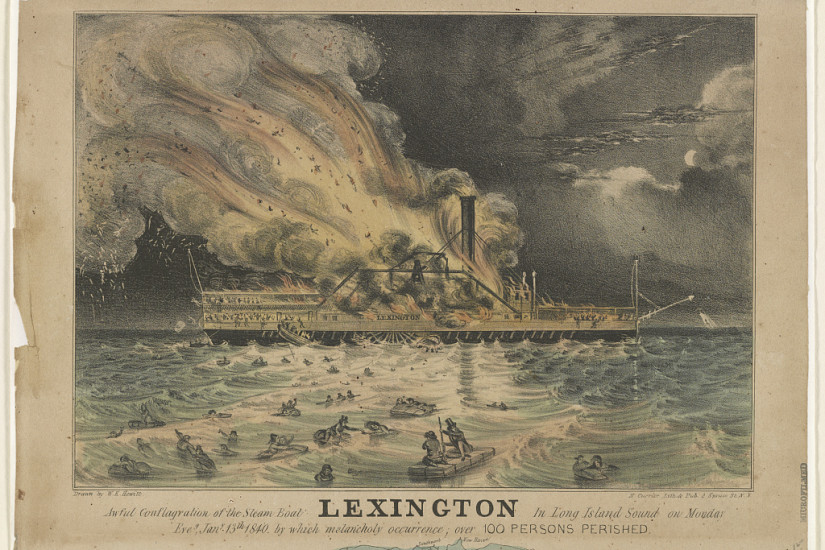

Within this broad understanding of disaster, Currier productions isolated very specific moments: his early prints favored newsworthy, dramatic ruptures in the destinies of a large number of people. The events to which he applied his presses were visually seductive, awe-inspiring public spectacles. Such representations offered an opportunity to reflect on these events and what they might mean for the viewer’s own condition. While individual reactions to historical images were seldom documented, an analysis of the sociocultural factors that inflected the viewing of Currier’s prints can provide insight into the conditions under which the images could generate meaning.

Rising from the Ashes: The Great Fire of 1835

Nathaniel Currier (1813–88) lived in tumultuous times. His own life trajectory and those of many of his associates arced across one of the most economically, socially, and politically volatile periods in American history—one marked by financial downturns, military conflicts, and massive physical and class dislocations as the tottering republic found its balance and matured into a modern industrial society. Currier’s seventy-five years on this earth also witnessed the advent of technological marvels—steam-powered ships and railroads—that remodeled the topography of the country and radically altered the flow of people within it. Such transformations brought with them the possibility of catastrophic conflict and sudden, grisly death on a grand scale. Visible evidence of this instability frequently recurs in the more than seven thousand images of the firm of Currier and Ives over its seventy-year existence. Fires and shipwrecks punctuate the perhaps more familiar collection of pleasant “scenes from American life” that range from kittens to sporting scenes to bucolic domestic tableaux. Into this mix, the publishers also injected scenes of deadly conflict from the Civil War and western expansion, as well as blatantly political, editorial, or socially prescriptive images.5 Such contrasts and tensions occur across the images of Currier and Ives’s oeuvre and, at times, within individual prints.