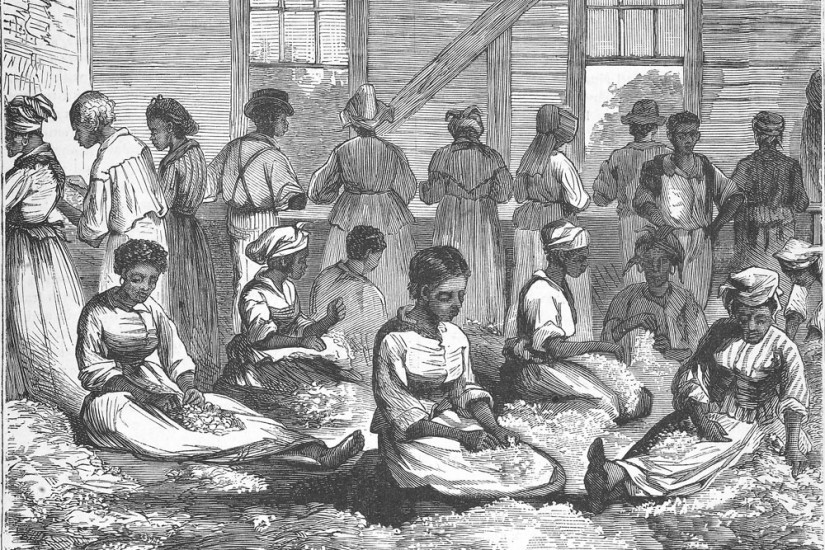

Four hundred years ago, “about the latter end of August,” an English pirate ship called the White Lion landed at Point Comfort in the Virginia Colony carrying “not anything but 20 and odd Negroes,” wrote colonist John Rolfe. Though this is often viewed as the starting point of slavery in what would become the United States, the anniversary is somewhat misleading. Africans, both enslaved and free, had lived in St. Augustine, in Spanish Florida, since the 1560s, and since slavery was not legally sanctioned in Virginia until the 1640s, early arrivals would have occupied a status closer to indentured servants. But those ambiguities only point to how essential people of African descent were to the establishment and development of the imperial outposts that became the United States. It was their work, as much anyone else’s, that helped build the world we live in today.

In his new book, Workers on Arrival, the historian Joe William Trotter Jr. shows that the history of black labor in the United States is thus essential not only to understanding American racism but also to “any discussion of the nation’s productivity, politics, and the future of work in today’s global economy.” At a time when mainstream political rhetoric and analysis related to economic change still tend to center on white men displaced by job loss in manufacturing and mining, similar challenges faced by black workers are often examined through a distinct lens of racial inequality. As a result, Trotter contends, white workers are viewed as the victims of “cultural elites and coddled minorities,” while African American workers suffering from the very same economic and political conditions are treated as “consumers rather than producers, as takers rather than givers, and as liabilities rather than assets.” Reminding us that Africans were brought to the Americas “specifically for their labor” and that their descendants remain “the most exploited and unequal component of the emerging modern capitalist labor force,” Workers on Arrival provides an eloquent and essential correction to contemporary discussions of the American working class.

Trotter acknowledges that he is not the first to offer this critique and cites generously from “nearly a century of research” and prominent African American scholars in order to demonstrate “the centrality of the African American working class to an understanding of U.S. history.” These include W.E.B. Du Bois’s studies of black working-class communities in Philadelphia, Memphis, and other cities during the turn of the 20th century, as well as Sterling Spero and Abram L. Harris’s 1931 book The Black Worker. But Trotter’s achievement is to synthesize this rich body of historical scholarship into a single volume written with an eye to a general audience.