In 1905, the poet George Sterling moved to Carmel-by-the-Sea, a coastal hamlet two hours south of San Francisco, to start an artist colony. The 36-year-old Sterling, nicknamed the “King of Bohemia,” was already prominent in literary San Francisco. He was Jack London’s best friend, a student of Ambrose Bierce, and the author of a single volume of poetry, The Testimony of the Suns, and Other Poems, published two years earlier.

At the time, Carmel was a tiny town near a Spanish mission that Father Junípero Serra founded in 1771. The stunning scenery—white-sand beaches, pine forests, and dramatic vistas—prompted several real estate developers to pitch Carmel as a resort. When would-be buyers resisted settling into the remote town, accessible only by stagecoach, the price of lots dropped: a $500 cottage could be secured with a $10 down payment or about $6 a month to rent, affordable even for artists.

Sterling envisioned a pastoral environment of beauty and simplicity where artists could devote themselves to their work. It would be a Bohemian Utopia, an idea he defined in a letter to Jack London:

There are two elements, at least, that are essential to Bohemianism. The first is devotion or addiction to one or more of the Seven Arts; the other is poverty … I like to think of my Bohemians as young, as radical in their outlook on art and life; as unconventional.

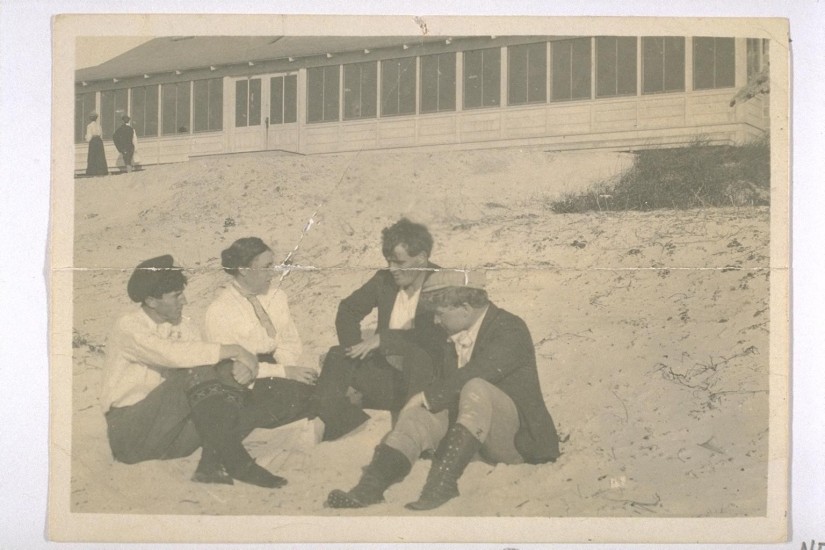

For at least a decade, artists flocked to Carmel, including writers such as London, Upton Sinclair, Mary Austin, Sinclair Lewis, Robinson Jeffers, Alice and Grace MacGowan, short-story writer James Hopper, and “muckraking” journalist Lincoln Steffens. Painters were also attracted to the town’s temperate climate and natural beauty, which helped inspire the California Impressionism school of art. Xavier Martinez, Francis McComas, Chris Jorgensen, E. Charlton Fortune, Armin Hansen, Guy Rose, and photographer Arnold Genthe all called Carmel home at some point.