The Sox’s Game 1 starter in the series, Cicotte had been reluctant to commit to the fix—but when he promptly hit the Cincinnati Reds’ leadoff batter, it was a signal that the deal was on. Given that the superiority of the White Sox was reflected in the betting odds, the first indication that something might be amiss—at least for those paying attention—was that so much money had suddenly been wagered on the underdog Reds. Several sportswriters who knew the team intimately, including the legendary Ring Lardner, made note of the improbable plays that seemed to occur at just the wrong moments—a bobble or misplayed fly ball here, a boneheaded decision there—and with grim humor came up with a parody of a popular standard:

I’m forever blowing ballgames,

Pretty ballgames in the air,

I come from Chi, I hardly try,

Just go to bat and fade and die.

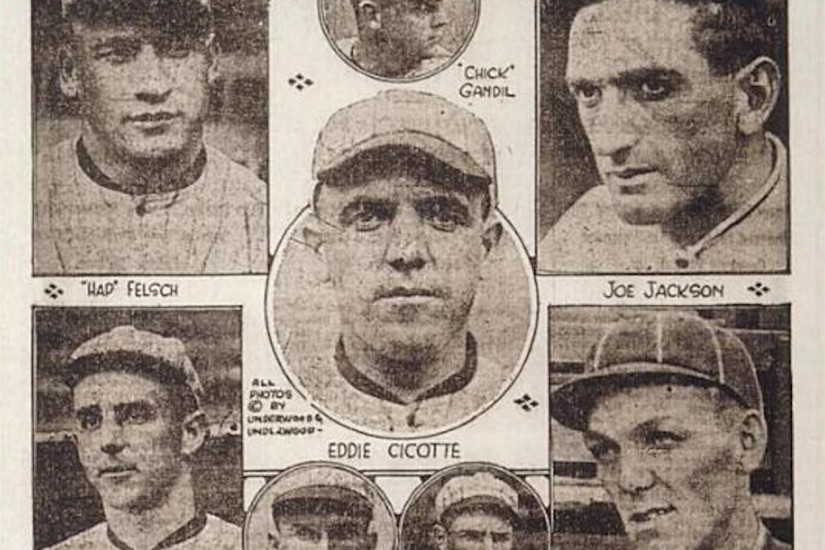

The Reds would go on to win what was then a best of nine series, five games to three. Yet for the Sox, the games would produce one unlikely hero in the person of the unheralded lefthander Dickey Kerr. The team’s third starter, unaware of his teammates’ subterfuge, Kerr pitched so brilliantly that the Sox won both his starts. (What’s less remembered is that Kerr’s career ended soon thereafter, when he was suspended by Comiskey and subsequently blackballed for holding out for better pay.) It would be a full year, the closing days of the 1920 season, before everything came to light, but once it did, photos of the disgraced eight dominated front pages everywhere. It remains difficult to fathom the scandal’s impact on the public, one almost unimaginably less jaded than we are today. “He’s the man who fixed the World Series back in 1919,” F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote five years later in The Great Gatsby, in introducing Meyer Wolfsheim, modeled on real-life fix mastermind Arnold Rothstein.

“Fixed the World’s Series?” the novel’s narrator Nick Carraway marvels:

The idea staggered me. I remembered, of course, that the World’s Series had been fixed in 1919, but if I had thought of it at all I would have thought of it as a thing that merely happened, the end of some inevitable chain. It never occurred to me that one man could start to play with the faith of fifty million people —with the single-mindedness of a burglar blowing a safe.

In fact, the timing made perfect historical sense. The recently concluded slaughter in Europe had changed America in ways just becoming apparent. Rather than peace and prosperity, the First World War’s conclusion produced widespread unemployment and dislocation. Fear of anarchism was rampant, and so, too, was racial violence—much of it generated by a reborn Ku Klux Klan. Cynicism was in the air; America’s prolonged age of innocence was over.