In a sweeping survey of Ta-Nehisi Coates’s place in the liberal rhetoric of the most recent turn of the century, Pankaj Mishra points to Coates’s struggle with a disconcerting question: “Why do white people like what I write?” We might also ask why white people like the film Black Panther, which, according to the director Ryan Coogler, was inspired not only by Coates’s work on the Marvel comic books but also his writings on race and identity. At an event in Harlem’s Apollo Theater, Coates described the film as “Star Wars for black people,” rhapsodizing that the film was “an incredible achievement. I didn’t realize how much I needed the film, a hunger for a myth that [addressed] feeling separated and feeling reconnected.”

Indeed, like Star Wars, Black Panther presents us not with science fiction but with myth, sharing with it what we might describe as “semi-feudal futurism” – a term far more appropriate for this film than “Afrofuturism,” thrown around in the mainstream media stripped of any meaningful political context. Why do white people love Black Panther, just as they love Star Wars?

If we take a cynical look, we might conclude that it is because two classic modes of white racism are reproduced in Black Panther. First, the notion that the value of a culture and people lies in the extent of its technological development, a condition rendered as a natural property rather than one which results from an unequal global division of labor and distribution of wealth. Second, that the opposition of the oppressed to their oppressors amounts to nihilistic violence, practiced by criminals with unworthy intentions.

If we are more forgiving of the white audience – that is, assuming their condescending benevolence – we might conclude that the appeal of Black Panther lies not in the racist stereotypes it reinforces, but in the way it discredits the ideals of emancipation and egalitarianism and replaces them with privilege and philanthropy. Following Parliament-Funkadelic’s 1977 indictment, in the year of Star Wars, of the commercialization and containment of the radical potential of black music, let’s call this mythology “the placebo syndrome.”

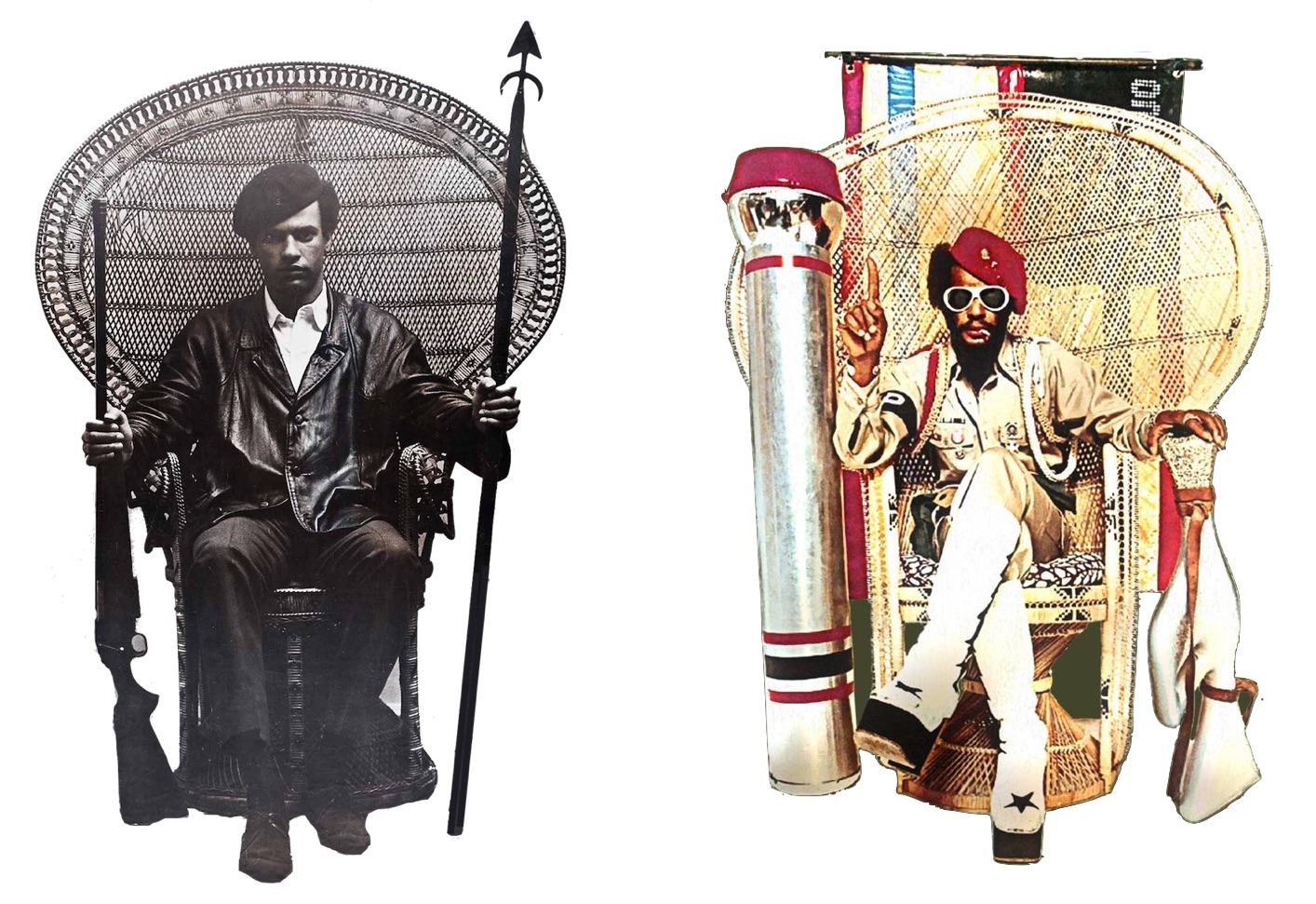

In the recent sequels, the semi-feudal futurism of Star Wars has been updated for an audience perhaps even less credulous of monarchies than it was in 1977, with Princess Leia converted into a general of a more or less republican anti-imperialist resistance. Black Panther is monarchist without apology. Its semi-feudal futurism is combined with the cultural nationalism historically associated not with the nominally connected Black Panther Party, but its adversary Ron Karenga’s US Organization – with which the Panthers had a violent shootout at UCLA leading to the deaths of Los Angeles Panther Captain Bunchy Carter and Deputy Minister John Huggins.