Cedric Robinson was fond of quoting his friend and colleague Otis Madison: “The purpose of racism is to control the behavior of white people, not Black people. For Blacks, guns and tanks are sufficient.” Robinson used the quote as an epigraph for a chapter in Forgeries of Memory and Meaning (2007), titled, “In the Year 1915: D. W. Griffith and the Rewhitening of America.” When people ask what I think Robinson would have said about the election of Donald Trump, I point to these texts as evidence that he had already given us a framework to make sense of this moment and its antecedents.

Robinson’s work—especially his lesser-known essays on democracy, identity, fascism, film, and racial regimes—has a great deal to teach us about Trumpism’s foundations, about democracy’s endemic crises, about the racial formation of the white working class, and about the significance of resistance in determining the future.

Through the intervention of film, a new American social order was naturalized.

—Cedric J. Robinson

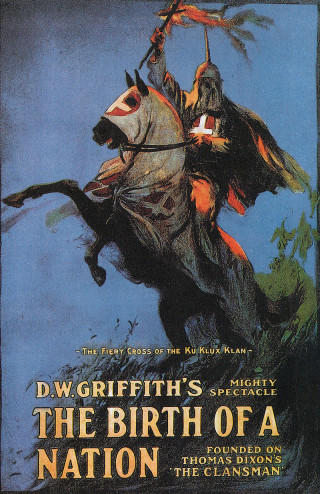

In 1915 William Joseph Simmons, an ex-preacher who made his income selling memberships in fraternal organizations, led a group of his friends atop Stone Mountain, just outside of Atlanta, burned a giant cross, and launched the revival of the Ku Klux Klan. His inspiration: seeing The Birth of a Nation, D. W. Griffith’s three-hour paean to the original Klan. Simmons believed the new Klan could make America great again by purging it of un-American influences: Negroes, immigrants (except for those of Anglo and Scandinavian stock), Catholics, and Jews. Under the slogan “100 percent Americanism,” the Klan pursued a program of severe immigration restriction, allegiance to the American flag, anti-communism, protecting white womanhood (and “correcting” wayward women who transgressed gender conformity, Protestant values, and the color line), better government, and law and order, while also engaging in lynching and open acts of terrorism against black people. The second Klan appears to be a ball of contradictions—antagonistic to both big business and industrial unions, contemptuous of both elites and a huge swath of the working class (the non-white and foreign-born). But as historian Sarah Haley recently argued, the Klan—whose membership rolls swelled to four million by 1924—mobilized a precarious middle class of small entrepreneurs, white-collar workers, and farmers facing the prospect of downward mobility and seeking hope in the elimination of the most marginalized segments of society.