It remains difficult to distinguish, in considering Benjamin’s life, between the striver’s earnest self-delusion and the schemer’s penchant for self-disguise. How invested was he in the Confederate cause and the system of human bondage it sought to perpetuate? What did he truly believe? And how were those beliefs shaped, if at all, by his highly attenuated Jewishness—the trait for which he is most commonly known today?

The task of addressing these questions has grown more pressing as pop-culture representations and public debates have turned Benjamin into a stand-in for the broader American Jewish relationship to slavery. In The Plot Against America, for example, Philip Roth’s fascist-friendly character Rabbi Lionel Bengelsdorf (a Charleston native and son of a Confederate veteran) professes the “highest regard” for Benjamin. In reality, American Jews have scrambled to distance themselves from the man. The only monument ever built to honor him, a concrete slab in Charlotte, North Carolina, was removed in 2020 at the urging of the city’s profoundly embarrassed Jewish community. As more or less the only file that comes up in our mental searches for “slave-owning American Jews,” Benjamin has become the favorite object on which to offload any sense of guilt.

But even as Benjamin’s story has assumed symbolic importance, a persistent lack of biographical sources has frustrated those seeking to interpret it. Evasive and inscrutable in life, he did everything he could to avoid becoming better known in death, including destroying almost all of his papers—not only while fleeing Richmond, but again two decades later, before his death in Paris in 1884. He once told a journalist who hoped to write a biography that he “should much prefer that no ‘Life,’ not even a Magazine article, should ever be written about me.” He didn’t get his wish, but for all we know about what really made him tick, he might as well have.

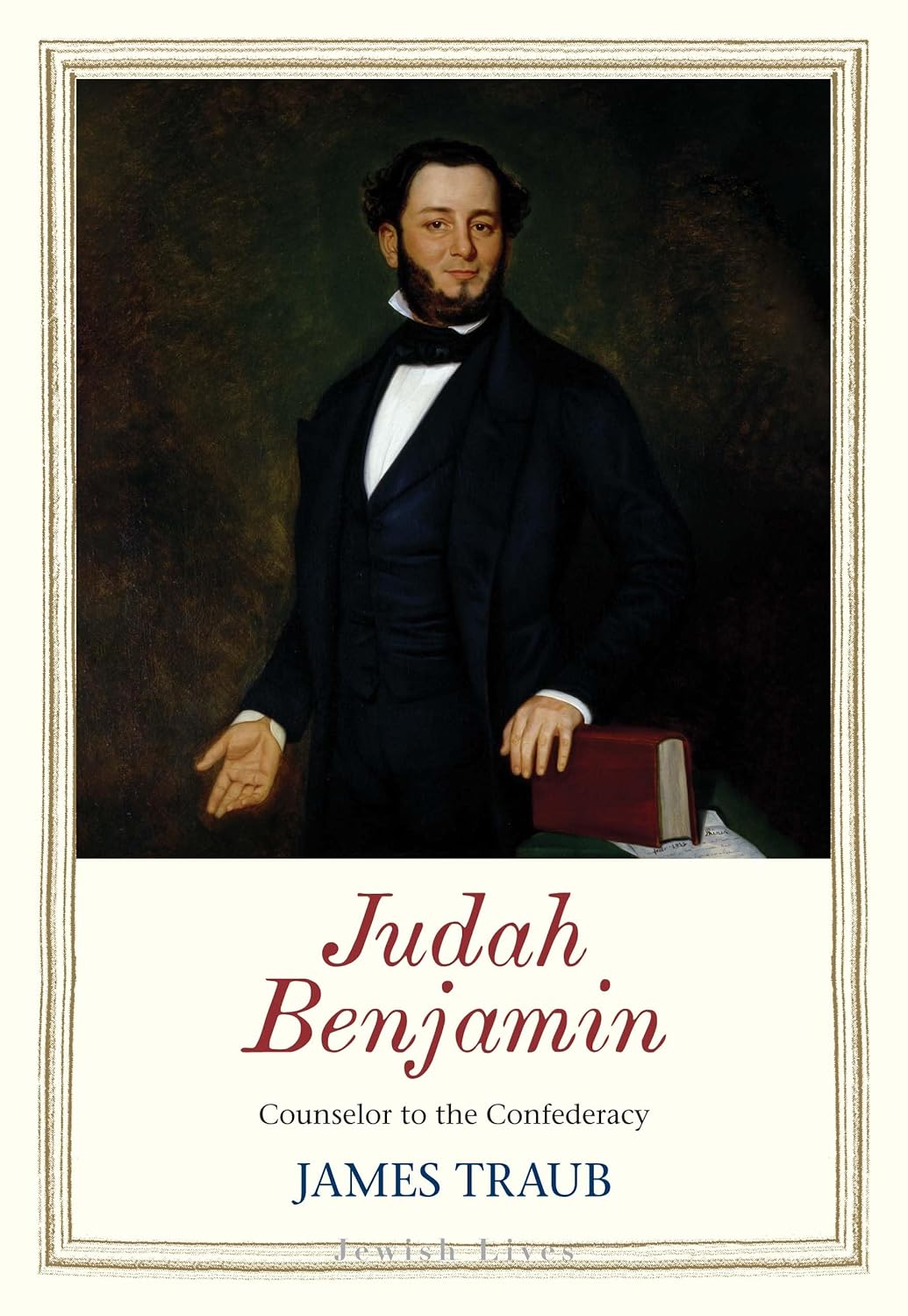

In a slim new biography for Yale University Press’s “Jewish Lives” series, veteran journalist James Traub—a columnist for Foreign Policy and the author of a well-regarded John Quincy Adams biography, among other books—tries to explain how the charismatic, talented Benjamin managed to become the consummate Confederate insider while remaining a conspicuous outsider in the land of Christian Southern nationalism. Traub’s pared-down narrative allows us to appreciate anew Benjamin’s improbable position as a Caribbean-born Jew in Jefferson Davis’s rebel court.

Even so, Traub’s tight focus on Benjamin keeps him from exploring the larger questions his subject poses. Benjamin’s ambiguous motivations for serving in the Confederate government can tell us only so much about the American Jewish encounter with slavery and the position of Jews in the nation’s racial hierarchy. If his story shows how the institution of slavery was shaped, in a small way, by the contributions of one Jewish individual, it does little to illuminate how slavery’s legacy and the systemic benefits of white supremacy have influenced the lives of all American Jews. In clearing the cobwebs off the little evidence we do have about Benjamin and dispensing with past biographers’ magnolia-scented smarm, Traub has succeeded in offering a valuable account of one man’s colorful and confounding life. But his judicious reconsideration ultimately serves less as a reminder of what we might learn by studying Benjamin in isolation than as an illustration of what we can’t.