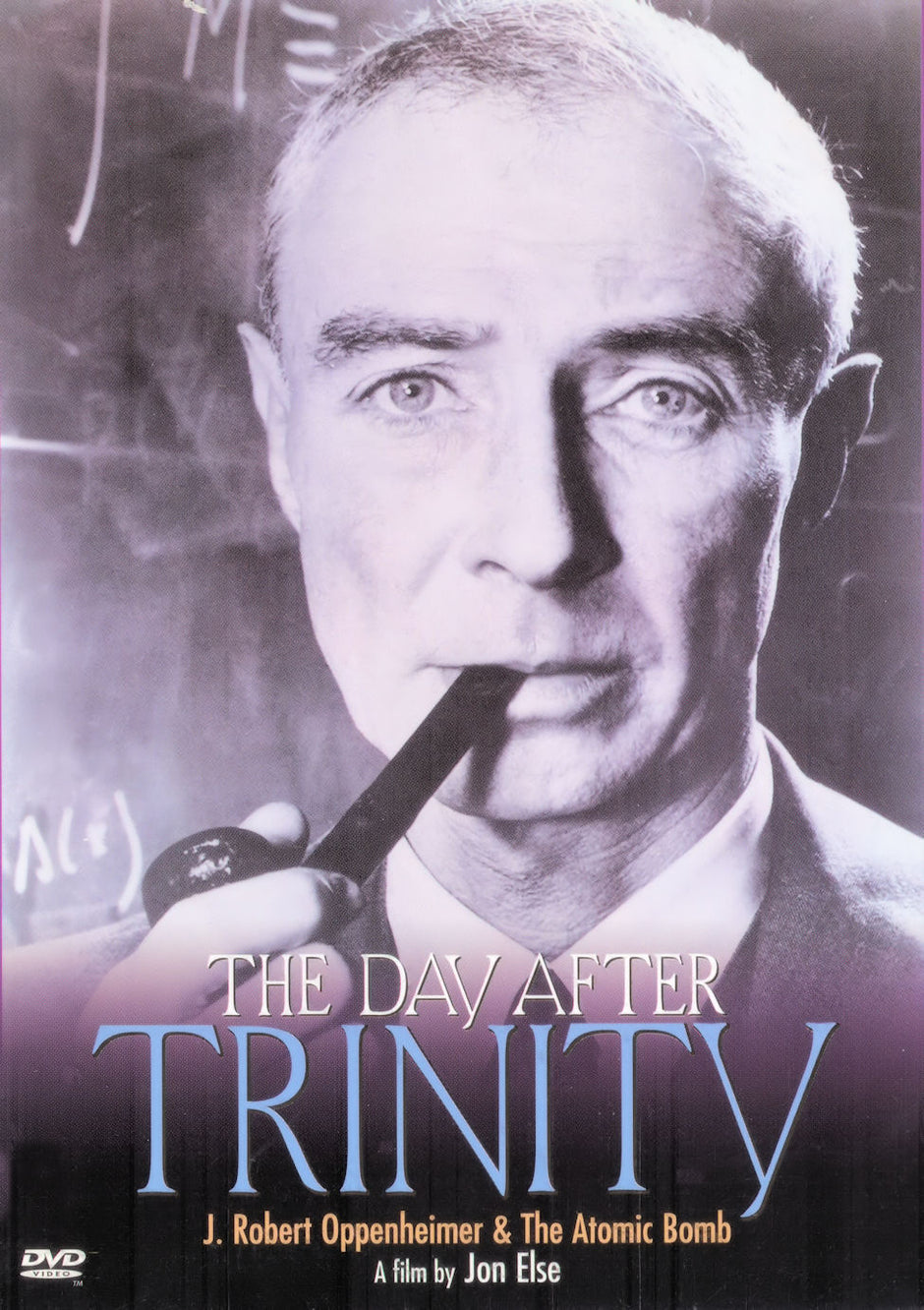

Oppenheimer positions the atomic bomb as the creation of a brilliant, creative personality. But The Day After Trinity revels in the administrative scale of the Los Alamos project necessary to make a mechanism to trigger, in a millionth of a second, a violent chain reaction with a flare brighter than a hundred suns. A walled city of six thousand staff, at a cost of $56 million. Seven scientific divisions: theoretical physics, experimental physics, ordinance, explosives, bomb physics, chemistry, and metallurgy. All of America’s industrial might and scientific innovation connected in this secret lab with its billions of dollars of military investment.

“Somehow Oppenheimer put this thing together. He was the conductor of this orchestra. Somehow he created this fantastic esprit. It was just the most marvelous time of their lives,” says Freeman Dyson, a rather eccentric theoretical physicist who became Oppie’s colleague at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. “That was the time when the big change in his life occurred. It must have been during that time that the dream somehow got hold of him, of really producing a nuclear weapon.”

In this vision of the A-bomb narrative, Dyson posits that Oppie’s aims switched from finding out “the deep secrets of nature” to producing “a mechanism that works. It was a different problem, and he completely changed to fit the new role.” We begin to see more clearly a portrait of an outsider with a wild desire to be at the center. All the work the whiz kids were doing over the years was always designed to contribute to the war. (All the films remove Oppie’s more demonstrably radical tendencies, his belief in a world government, for instance, which he mentioned offhandedly in the New York Review of Books in 1966.)

The closest we get to Oppenheimer himself is his pale-eyed, doppelganger brother, Frank, who gives the impression of a visionary living in a purely abstract realm. He stammers a little when he speaks of the moment when he and Oppie heard on the radio of their great bomb in action. “Thank God it wasn’t a dud… thank God it worked… Up to then, I don’t think we’d really, I’d really, thought about all those flattened people.” He still seems stunned. If nothing else, Frank gives weight to the storytelling trope of scientists as hyperintelligent but flakey space cadets at a remove from the humanity of it all. “Treating humans as matter,” as Los Alamos collaborator Hans Bethe puts it appallingly. Another contributing scientist says he vomited and lay down in depression. “I remember being just ill,” he says. “Just sick.”