Since the Supreme Court handed down its decision over a decade ago in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, political analysts and voters have complained about the role of money in federal elections, frequently blaming the 2010 ruling. While the decision undeniably impacted the electoral landscape, the SCOTUS opinion in Citizens United is not actually ground zero for campaign finance reform. Rather, a 1976 decision by the Court in Buckley v. Valeo more essentially established the Court’s role in defining the issue for the next half century.

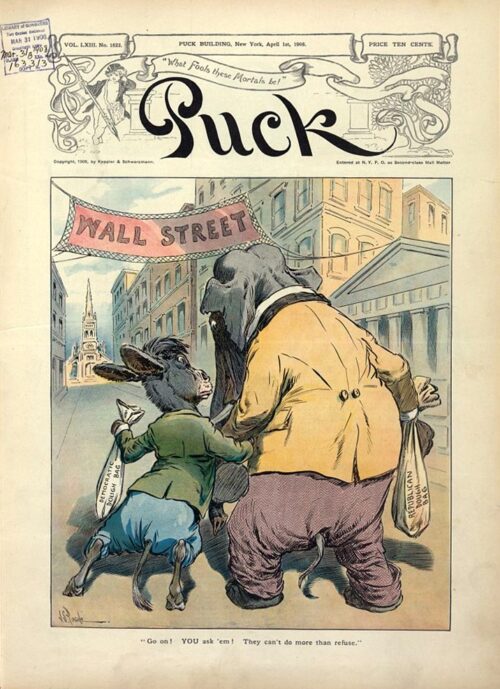

Before delving into the case, however, it’s useful to know the broad legislative history of the law. During the Progressive Era (roughly 1890-1920), fears regarding the influence of big business on elections resulted in the passage of laws in 1907 and 1910 banning corporate contributions to federal elections and forcing national parties and multi-state committees to disclose campaign contributions. Amendments followed in subsequent years that included expenditure caps, contribution limits, and increased disclosure requirements.

The laws, however, generally lacked any real enforcement mechanisms. No government agency assumed responsibility for enforcement, and the legislation contained so many loopholes they were functionally useless. President Lyndon Johnson described it as “[m]ore loophole than law,” which ultimately invited “evasion and circumvention,” two aspects of politics with which LBJ was not unfamiliar.

Controversies often fuel new campaign finance legislation, as Anthony Johnstone observed in 2014. In 1970, President Nixon vetoed the Political Broadcasting Bill, an effort by Congress to rein in media spending by campaigns. This, among other controversies, drew new attention to the need for better regulation. As a result, the House and Senate passed the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA), which Nixon signed into law in 1971.

FECA replaced the previous campaign finance laws passed earlier in the century. Among other measures, the Act created the Federal Election Commission (FEC) to enforce the law and eliminated the contribution and expenditure limits.

Three years later, driven by the Watergate scandal and with 90 percent of the public believing that campaign spending had careened out of control, Congress passed amendments to the 1971 act that added ceilings on campaign expenditures, limited campaign contributions, and established publicly financed presidential elections.