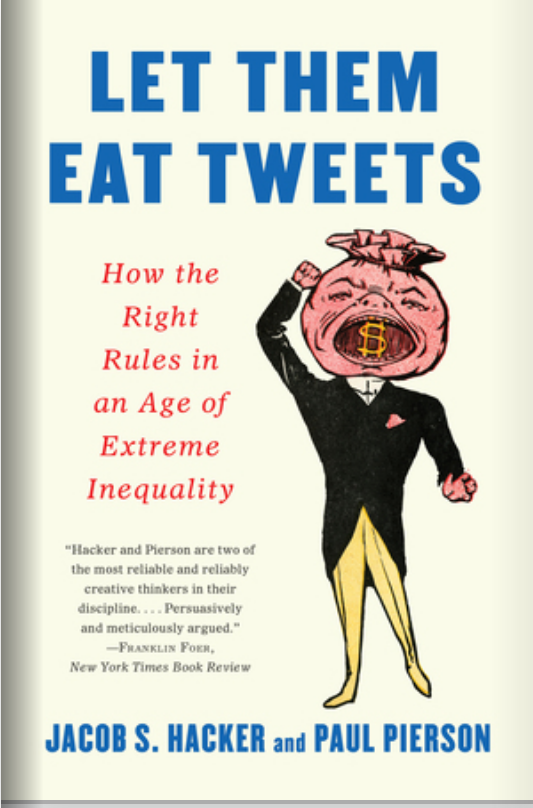

How did the Democrats lose the Baileys? Two new books are the latest to take on the question: David Paul Kuhn’s The Hardhat Riot: Nixon, New York City, and the Dawn of the White Working-Class Revolution uses narrative history to make an argument that has been recited so often since the late 1960s that it has taken on a ritualistic quality: to be American is not enough, one must be positively so. Fail to perform the proper rites of patriotic adoration, and the Cossacks will come riding in on the Long Island Expressway, pillaging and burning. This is ersatz class analysis, which passes off the most privileged fraction of the working class as a stand-in for the whole. Jacob S. Hacker and Paul Pierson’s Let them Eat Tweets: How the Right Rules in an Age of Extreme Inequality traverses somewhat similar territory. Taking a more serious approach, these eminent political scientists see Trump as the result of a crisis of the historic compromise between elites and democracy, and the phenomenon of rank-and-file support for oligarchy as a kind of politics of distraction. Though more clear-headed, their book, too, rests on mechanical assumptions about the relationship between class and political behavior.

It’s time to abandon this story, which assumes both that workers have a “natural” home on the center-left, yet also that social conservatism always lies latent within working-class culture, available for the right-wing politician ready to activate it. Rather, the establishment of working-class solidarity in industrializing societies between roughly 1870 and 1970 was the deliberate effort of the countless militants and activists who turned a shared social experience into a common political orientation. Certainly, the defeat of the workers’ movement in the decades since has been aided by the fanning of the flames of cultural grievance. But while this reversal has benefited elites and the culture-warrior right-wing politicians they own, others too have stood to gain.

What both of these books miss is the role of liberal politics in the erosion of working-class solidarity. Since the early twentieth century, liberal politicians have both depended to some degree on such solidarity to supply mass support and at the same time sought to contain it to sustain their own position. When this project of containment succeeds, class itself begins to diminish as an organizing political force—empowering liberal politicians, but producing oligarchy for society at large.