In our digital age, the limitations of traditional commemorative practices – monuments, statues and plaques, the tired hierarchy of granite and bronze – are clear. They proclaim a single, narrow story; they lack context and interpretation; they often reflect the needs of the era they were constructed in, rather than what they represent or who they serve today; and they can’t be annotated, despite the clear desire of Americans to do so (earnest attempts have included graffiti, stickers, and a pink pussy hat.) They aren’t even permanent, despite the intent of those who no doubt lobbied hard to gather the capital, legal permission and public will to create them.

These practices don't serve our modern needs. So what can we do?

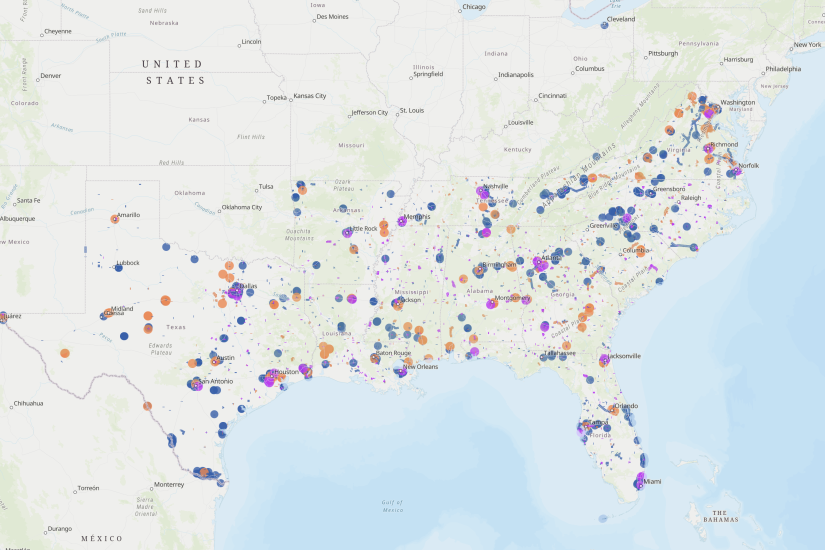

For now, this atlas offers an intervention. The Digital Atlas of Southern Memory presents a prototype of a new form for visualizing and practicing broad-based, citizen-driven commemoration.

What’s a digital intervention for commemoration?

In an era of fervent memorialization and contentious debates about who and what should be commemorated in the public sphere, the conversation has largely been limited to physical monuments such as statues, plaques and landmarks. These structures advance narrow cultural narratives about the past, require significant capital to establish, and allow for no interaction or annotation by the public. As a result, there is little opportunity for most Americans to participate in what gets remembered – and yet the hunger is there, visible in heated debates, defaced statues and renamed spaces cropping up in communities across the nation.

With a theoretical underpinning in collected memory studies and public history, the Digital Atlas of Southern Memory (DASM) presents a prototype for a platform that can enable broader participation in the commemoration process. It aims to be an engine for doing what public history, at its best, should do: meet modern, digital audiences where they are; help them connect with their own history, and awaken a curiosity – and usually, an opinion – about what they hope will be remembered.

Located in the American South, a region that historically has taken an active role in constructing narratives about its past, the DASM is comprised of two parts:

The visualization reveals what people in the region choose to remember through monuments, named public spaces and other commemorative forms. The prototype showcases names of public schools and streets in order to surface narratives that are more subtly embedded in daily life than statues and plaques.

The interactive component provides a forum for the public to alter the record of collected memory if they find that the dominant narratives don’t tell their story. Users can add new digital monuments; hold debates about statues and named spaces; and annotate existing ones by providing context, suggesting alterations or expressing an opinion. The prototype invites suggestions for new “memories” and for adding context to existing sites.