So much of Charles Ives’s music has its origins in the small-town New England of his youth. His fertile period roughly corresponded with the first two decades of the 20th century, and as America hurtled through that turbulent and transformative era, Ives sought to preserve in his compositions certain memories from his past: bands belting out patriotic tunes as they marched down Main Street, a congregation singing on a Sunday morning, the sounds of a church bell ringing or a fiddler fiddling or a crowd cheering on a village green. This was the world of Danbury, Connecticut, in the late 1870s and ’80s. It was the world of his father (who had led a band during the Civil War and later became the town’s bandmaster) and that of his distinguished grandparents, who had kept company with the transcendentalists. Ives’s style allowed for a generous amount of quotation—of hymns, marches, popular songs, and other kinds of American vernacular music. Thus was he able to evoke, in a singular, visionary way, a world that had seemingly been lost.

Take, for example, Ives’s Holiday Symphony, comprised of four movements composed independently of each other, each depicting a different seasonal American celebration. Parts of the work are iconoclastic, so rhythmically and harmonically complex that you could never say that Ives was trafficking in mere nostalgia. This is music that combines memory and radical innovation, nowhere more so than in the symphony’s third movement, The Fourth of July.

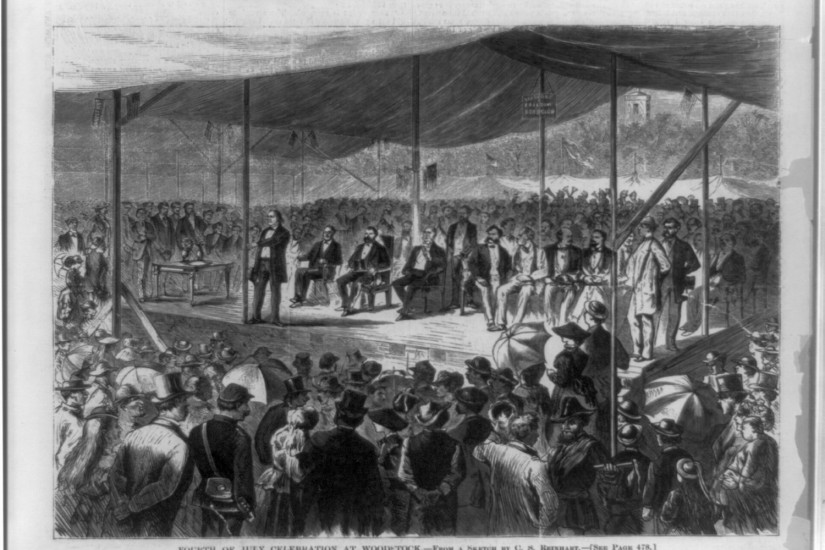

The Independence Day celebrations of Ives’s youth were wild affairs, to say the least, raving drunkenness and altercations being the order of the day. On July 4, 1874, the year of the composer’s birth, several fights broke out in Danbury. One man was stabbed, another suffered injuries in a fireworks mishap, and a fire broke out in town, one of four in the region that day. The typical Fourth would also have included quite a bit of oratory, with speakers intoning the glories of the Founding Fathers and touching on other patriotic topics. Ives’s musical Fourth of July preserves all of the tumult but none of the sober high-mindedness. “It’s a boy’s Fourth—no historical orations—no patriotic grandiloquence by grown-ups—no program in his yard,” Ives wrote, shortly after completing the work in the summer of 1912.